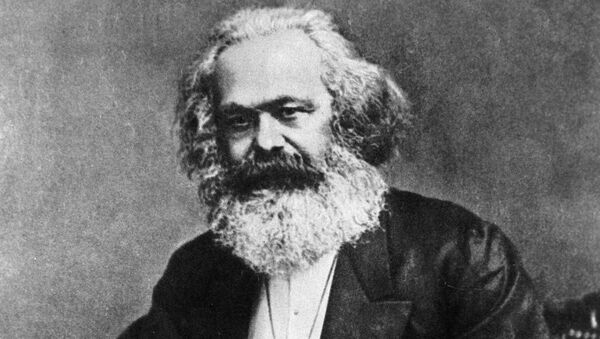

Karl Marx is a name known by many, and most associate it with communism. This would be not strictly true, as the most known forms of communism – that in the former Soviet Union or China – are not entirely what the German-born philosopher had in mind. He was born in Prussia in 1818 into a middle-class family, and his early life was not entirely unpleasant or full of hardships. This was soon to end as he became interested in controversial political ideas and began writing for radical newspapers.

In 1842, at the sunset of colonialism, in the younger days of free trade and global capitalism, Marx became a journalist, working for Cologne-based Rhineland Newspaper, writing articles in which he expressed his early views on socialism. The Prussian government censors soon cracked down on the newspaper, insisting on authorizing every issue before publishing, before eventually banning it altogether. This did not discourage Marx, who moved to Paris and became the co-editor of the German-French Annals newspaper in 1843. Wages everywhere had been falling for two decades, while the cost of living was on the rise. The situation was exacerbated by food shortages of 1844. Marx’ views, which eventually came to be known as Marxism, crystallized by this time.

Mary Gabriel, in her Pulitzer Prize nominated book Love and Capital: Karl and Jenny Marx and the Birth of a Revolution, wrote:

Although he had once discounted communism as unrealizable, Marx now saw it as the means to recalibrate society. Wealth would not be private property but shared. Men would work, but their work would benefit themselves and the greater good, not the property owner.

Marx openly supported taking against such injustices, and vocally supported riots, which occurred in the Prussian province of Silesia. In the summer of 1844 Marx began expressing his radical views in the Paris-based uncensored Forward! newspaper. The Prussian government was not happy about it and in 1845 pressured France to take action. Its editor in chief was imprisoned, and the staff – including Marx – were expelled from the country.

Forced to seek a new home, unwelcome in either France or Germany, Marx moved to Brussels, not discouraged, but newly fueled to continue his work on capitalism and communism – it was there where he met Engels, his eventual friend and collaborator. During the next few years he polished his ideas, moved back to Cologne and played a role in failed revolutions of 1848 – a role that eventually had him expelled from continental Europe.

In 1849 Marx eventually sought refuge in London, where he initially lived in poverty. There he was careful not to support what he called ‘adventuristic’ ideas of the Communist League – starting spontaneous revolutions across Europe. However, Marx did not abandon his views on the necessity of a revolution, arguing that the correct way was to first go through different stages of social development. Marx lived to witness one such revolution. Following the collapse of the French Second Empire, Marx wrote:

The great social measure of the Commune was its own working existence. Its special measures could but betoken the tendency of a government of the people by the people.

The Commune eventually failed to live up to the expectations, and Marx failed to see his vision of communism implemented in real world. Perhaps it was persecution by the authority, as well as years in poverty, which shaped his philosophical views – views, which eventually toppled governments and ruled national policies for decades.