In his interesting and highly original analysis, recently published in The National Interest magazine, Awan, an Associate Professor in Modern History, Political Violence and Terrorism at the University of London, pointed out the "eerie parallels" between the terror attacks which struck Paris last week and those which had hit the city over a century earlier.

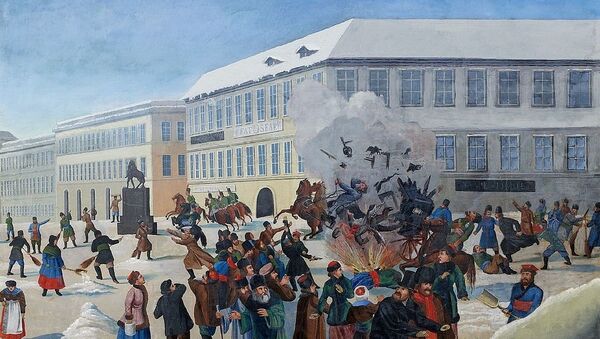

The professor recalled that "these angry young radicals used bombs and guns to terrorize their own societies in furtherance of a foreign creed, in much the same way that jihadists recently did in Paris."

In fact, "if there is one salient difference," according to Awan, it is the fact "that the anarchists were actually far more successful in their campaign than the jihadists today. In a short period of time, they managed to assassinate an impressive list of world leaders, including two US presidents, the Russian tsar, the German Kaiser, the French and Italian presidents, the Italian king, the Austro-Hungarian empress and two prime ministers of Spain, as well as a whole host of the European ruling classes."

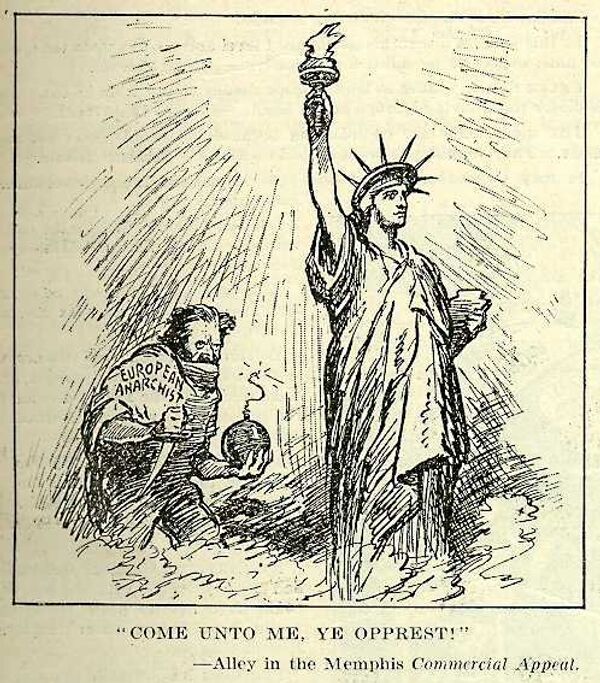

"The assassination of US President William McKinley in 1901, for example, by an anarchist who also happened to be a second-generation Polish immigrant, led to the expedited introduction of anti-immigration legislation which required the exclusion and deportation of anyone suspected of anarchist sympathies. Anti-anarchist propaganda images from the period are disquietingly reminiscent of the increasingly hardened attitudes we are already witnessing toward Syrian refugees."

"In the European mainland," the scholar continued, "wide-scale surveillance of meetings and publications was followed by arrests and torture, and used to draw forced confessions. Indeed, various Western governments used the ominous threat of anarchist terror to then subdue any form of dissent against the state."

"All of this," the professor suggested, actually "had little tangible effect on the anarchists themselves," with those who were executed actually "often transformed into martyrs." Furthermore, "the apathetic masses, who up until this point had remained largely indifferent to the anarchists' propaganda, were increasingly polarized by the state's draconian response. Indeed, the harder the state clamped down, the more powerful the movement became."

Lessons From History

According to the professor, the fact that most people today have "probably never heard of the anarchist reign of terror at all" is one of the most important points in considering the appropriate responses to the threat of jihadist terror.

"Despite the spectacular violent successes of anarchist terrorism at the time –far more so than those of the jihadists today –anarchism achieved very little in the sociopolitical sphere in the long run. Within four decades, the violent ideology had consumed itself and in the process alienated any potential support base, quickly being replaced by more popular movements. The anarchists were soon forgotten and ultimately consigned to the wastebin of history."

This, the professor believes offers contemporary observers "two crucial lessons for dealing with the jihadist threat today. First: do not overreact. Second: do not, through fear, hand over excessive power to the state."

Analyzing the theories expounded by flagship ISIL propaganda magazine Dabiq, the professor pointed out that the terror group's theorists have been speaking quite openly about their plans to eliminate the 'grayzone' – the "liminal space in which young Frenchmen could be both Muslims and good citizens of the Republic, without any inherent contradiction."

The group's terror attacks, Dabiq noted, would force "Western Muslims…to make 'one of two choices': between apostasy or IS' bastardized version of belief." For his part, Awan pointed out that the magazine even approvingly cited "George W. Bush's central dictum that underscored the Global War on Terror," that "the world today is divided into two camps," and that, in Bush's words, 'either you are with us or you are with the terrorists."

Noting that the public's fear can lead them to agree to pretty much anything, "from the NSA's unprecedented mass surveillance regime to…legal black holes like Guantanamo, [to] extrajudicial assassination by drones to the sanctioning of torture," Awan warned that "and of course, many things that we do not agree to nevertheless end up on the roster too."

"This," the professor explained, "is the danger of the slippery slope, or function creep. Big data algorithms, used to decide who is placed on the drone strike kill list abroad in Yemen, might suddenly find their way into predicting civil unrest and dissent in places at home like Ferguson. We might not have approved the latter, but by then it is too late –the genie's out of the proverbial bottle."

Ultimately, Awan suggests that in seeking to fight the threat of jihadist terror, Western nations must "not lose sight of who we fundamentally are as open, liberal, democratic societies." In this vein, they would do well "to heed the experience of dealing with the anarchist scourge from over a century ago."