Kristian Rouz – That means the Fed will have to interfere with bank sector operations with administrative directions in order to stave off future crises.

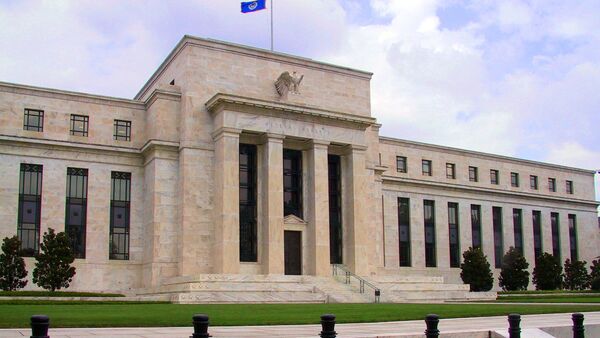

Even though the US Federal Reserve hiked borrowing costs in December amidst the upbeat macro indicators and a brighter outlook into the coming year, the regulator is still concerned with the remaining slack in the US banks’ lending policies.

Consequently, there is a credible threat of asset bubbles emerging in the hottest areas of the US economy, fueled by credit and directly related to already solid domestic consumption.

The US Federal Reserves’ ‘macro-prudent’ monetary policy strategy might turn out to be insufficient to stave off the emergence of hazardous asset bubbles in the US economy in 2016, as outlined in the joint message by the Fed, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. and the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency. Most prominently, commercial banks nationwide were warned in December of their overtly loose lending policies.

The US real estate market is booming all across states, from New England to Western outposts of the Bible belt to the Northwest, with increasing numbers of Americans having taken mortgage loans in the outgoing year. The mortgage boom is set to expand into 2016, with even the stereotypical ‘single female homebuyer’ back in the market.

The main Fed’s concern is that commercial banks might be prone to the issuance of potentially unhealthy loans, primarily, to people whose ability to service their debts in the long term is questionable.

On May 4, 2004, the US Fed base interest rate stood at 1.00%, however, in response to the robust credit-fueled expansion in the economy, the regulator undertook 17 hikes in rates between that date and August 8, 2006, raising borrowing costs by 0.25% each time, with the base rate reaching 5.25%.

High rates persisted throughout the following twelve months, but is was too late: the mortgage bubble popped in 2007, and on August 17 that year the Federal Reserve started gradually loosening monetary conditions attempting to spur expansion in other sectors of economy, attracting capital there.

However, even though the rates reached near zero in December 2008, the financial collapse followed by a full-blown global economic crisis were inevitable.

The reason is the insufficient rapid expansion in the real economy. Between May 2004 and August 2006, the US economy grew an average 3.03% per year, whilst the current pace of the US economic expansion is at 2.2%. Meanwhile, the historical average is 3.3%.

The Fed’s potential inability to constrain asset bubbles is also stemming from the fact that the current inflation rate is below the targeted 2%, meaning the regulator wants some stimulus to remain until the price index growth accelerates. Between 2004 and 2006, US inflation was between 2.7-3.2%, easily allowing for tightening measures.

Now, in 2014 the measure was at 1.4%, slowing down to 0.2-0.5% during the first ten months of 2015. The December hike might have impaired already weak inflation, meaning there is no room for the Fed to act in response to possible asset bubbles.

“The Fed is clearly more sensitive than they were in the past,” Mark Mason of the Seattle, WA-based HomeStreet Bank said. “They were reactive last time, and they need to be preemptive.”

In other words, the Fed is now intending to make it mandatory for banks to have their own safety bags should their borrowers fails to service their debts. Previously, during the Alan Greenspan era, the Fed believed the banks would do that same thing on their own initiative, as such measures would be in their best interest.

However, the banks opted to maximize their expected profits by putting all of their capital into market operations – some taking on the risk out of greed; others believed they were too big to fail in the eyes of the government.

That degree of banks’ self-exposure to risk cost the US government hundred billions of dollars. This time around, Washington, while making it clear there will be no bailout, also directly intervened into the financial sector to prevent the 2007-2008 scenario.

“The regulatory environment post-crisis has been a lot better-geared toward getting ahead of a lot of the instability,” Gennadiy Goldberg of the New York-based TD Securities said.

However, all that means there is increasingly more government involvement in the US economy now, leaving much less space for private initiative and overall economic freedom. The way Washington is fighting financial crisis is quite similar to the approach in the ongoing war against terrorism: moderate, yet questionable success in a struggle against evil comes at a price of shrinking freedoms for the entire nation of the United States.