On January 15, 2015, SWAT teams cornered a group of terrorists armed with Kalashnikovs in a warehouse in the eastern Belgian city of Verivier. However, the Tony Montana-style standoff ended badly for members of the Daesh-affiliated group. Two men were killed on sight, while a third was severely wounded. All three had just returned from Syria and were planning to kidnap and kill a Belgian policeman…live on webcam.

Terrorism is a serious problem for Belgium. Even though the country is home to NATO's headquarters, the International Center for the Study of Radicalization recently named the land of chocolate and waffles the leading source of manpower for Sunni militant organizations in Syria and Iraq among the EU member states.

Belgium’s authorities say they’re doing what they can to thwart the terrorist threat. Unfortunately, so-called “lone wolf” radicals are very hard to detect.

The country’s interior minister Jan Jambon voiced his concerns at Politico’s What Works event in Brussels:

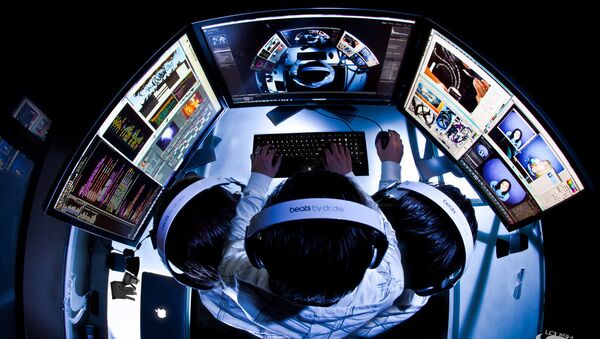

“What I’m afraid of is the guy who sits behind his computer searching the messages of IS (Daesh) and of the hate preachers, and then at a certain moment he’s able to commit violent acts and he comes out and he goes to the train station and he does these things. I don’t think it can destabilize our society, but it can evoke a lot of harm to our people. And that is what I’m afraid of.”

Computer science was Jan Jambon’s university major. But that was back in 1984, when computer technologies posed little or no danger. According to Jambon, now government agencies are facing new challenges, like intercepting terrorist communications on popular gaming consoles:

“I’ve heard that the most difficult [way of decrypting] communication between these terrorists is the Playstation 4. It’s very difficult for our services, not for Belgian, but for international services to decrypt communication that is going via Playstation 4.”

The part about Playstation 4 made waves on the Internet later that year, when Forbes contributor Paul Tassi wondered whether radicals are already using popular console games to coordinate their activities:

“An ISIS agent could spell out an attack plan in Super Mario Maker’s coins and share it privately with a friend, or two Call of Duty players could write messages to each other on a wall in a disappearing spray of bullets. It may sound ridiculous, but there are many in-game ways of non-verbal communication that would almost be impossible to track.”

But if the gaming theory still sounds a bit too far-fetched, the use of so-called hidden web services by Daesh members is a fact.

The Onion Router technology, or Tor, allows people to visit websites anonymously with the use of a special browser. With Tor it’s possible to keep the website unreachable for regular search engines and its visitors can only see it by going through a chain of randomly selected servers, or nodes. It’s harder for governments to track down and close Tor websites, and it’s certainly more difficult to trace individual visitors of hidden websites.

In November 2015, Daesh, which is known for its use of the Internet, launched a mirror of its propaganda website on the Tor network. The link, together with instructions on how to use Tor, was posted on a Daesh discussion forum and advertised on Twitter.

But the high-tech jihadi project ended abruptly. And it wasn’t the government who silenced the new bullhorn of Daesh propaganda. Ghost Sec, a faction of the hacktivist collective Anonymous, took down the website, replacing the front page with Viagra and Prozac ads and a following message to jihadists:

"Too Much Daesh. Enhance your calm. Too many people are into this Daesh-stuff. Please gaze upon this lovely ad so we can upgrade our infrastructure to give you the Daesh content you all so desperately crave."

As terrorists continue to use the latest computer technology, law enforcement agencies all over the world are struggling to catch up. As long as there is no sure-fire way to keep Daesh off the Internet, it looks like the online battle on terror is far from being won.