Since Friday's abortive coup attempt by elements of the Turkish military, the Turkish government has cracked down hard against the alleged culprits, arresting thousands of military personnel, with over 8,000 police officers, civil servants and regional governors dismissed from their jobs. Reuters has estimated that about 50,000 people have been arrested or suspended from their posts and jobs in the mass purge following the coup attempt.

Prior to Friday's failure, the Turkish military had repeatedly and successfully forced the country's leaders to resign or to change the country's political course. What was different this time?

The excerpt begins by recalling that the Turkish armed forces' special role in the country's political life was formulated by post-Ottoman Turkey's founder – Mustafa Kemal Ataturk. Effectively, "the army was assigned the task of ensuring the republic's security against enemies both foreign and domestic, and of serving as the guarantor to the reforms and modernization of society and the economy."

"So were created the prerequisites for institutionalized military intervention into the political life of the country, though Ataturk personally was convinced that the army must be separated from politics." Accordingly, "officers were not allowed to stand as candidates in elections; when starting a political career, they were forced to first resign from the military, as was done by Ataturk himself."

"To carry out his modernization project, Ataturk created the Republican People's Party (CHP) in 1923. In 1931, the CHP adopted a program consisting of 'six arrows' – the principles of Kemalism: republicanism, populism, nationalism, secularism, statism and reformism. These principles became the doctrine of the ruling party and, in 1937, were also enshrined in the constitution."

Crucially, "since its founding, the Turkish Republic's army has always proclaimed its loyalty to the six principles of Kemalism."

"At the same back, as far back as 1945, secret groups appeared within the Turkish officer corps who planned military coups to overthrow the CHP and establish a multiparty system. With the coming to power of the DP, these officers pinned their hopes on the new government to make changes to the social and economic situation for military personnel, to carry out of urgent military reforms and to rejuvenate the command structure. However, the DP did not live up to their expectations."

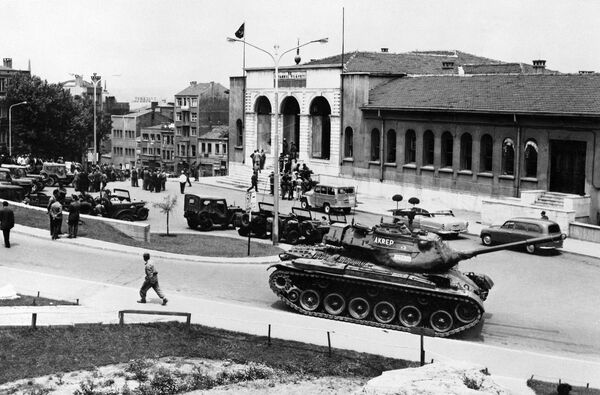

May 26, 1960: The First Coup

In the late 1950s, the DP attempted to ban the CHP, resulting in massive social unrest and clashes between the supporters of each party.

Thus, Vasilyev recalled, "on the night of May 26, 1960, soldiers from the Ankara Garrison and cadets from military academies under the command of Colonel Alparslan Turkes captured all the administrative buildings in the capital. Political power was transferred to the so-called National Unity Committee, led by General Cemal Gursel. The DP was banned and its leader, Prime Minister Menderes and his supporters were tried and executed."

Soon after the coup, a political struggle emerged within the National Unity Committee between supporters of a moderate course and a return to multiparty political life and radicals, who demanded the establishment of a military dictatorship.

"As a result" the book noted, "the army was purged of radicals and its old cadres, in the course of which over 5,000 officers deemed unreliable were dismissed. In 1961 a new constitution was adopted, formally justifying the military intervention of May 27. On October 15, 1961 Turkey saw parliamentary elections. However, the CHP did not win enough votes to form a majority government, and entered a bloc with the newly formed Justice Party (AP)."

1960s-1970s: Run-Up to the Second Coup

After the 1960 coup, the military continued to control the political situation indirectly. In 1965, new parliamentary elections were held, won by the Justice Party. In 1969, the AP retained its majority.

Subsequently, against the background of growing social unrest, on March 12, 1971, Chief of Turkish General Staff Memduh Tagmac published a memorandum demanding the dismissal of the ineffective government of Suleyman Demirel, the founder and leader of the AP, and the formation of a new government charged with eliminating social unrest and carrying out reforms. "It was emphasized that otherwise the armed forces would be forced to intervene."

The government resigned, although the military preserved the existing parliament to amend the constitution, and did not try the AP leadership. At the same time, "the army tightened press censorship, banned strikes and rallies, and carried out a series of arrests of political activists."

Third Coup

Following elections in October 1973, power was once again transferred to the parties. The vote was spread out between the CHP, the AP, the National Salvation Party [an Islamist party] and the MHP. No party won a majority, and between 1974 and 1980 the country was governed by seven different coalition governments.

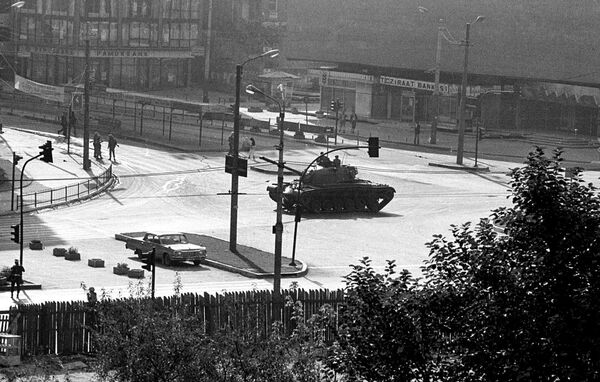

"By the late 1970s, against a background of economic hardship and the government crisis, Turkey once again faced bloody political clashes. After an appeal to political leaders to unite to overcome the crisis proved inconclusive, a military coup was occurred on September 12, 1980. Power was transferred to the National Security Council, headed by Chief of General Staff Kenan Erven, and a non-party-based government was formed. Existing parties were disbanded, their leaders arrested and assets transferred to the state."

Press censorship was further tightened, "as was control over the universities, considered the main centers for the distribution of leftist political ideas."

Soon after the coup, the military again announced its intention to restore civilian rule. "In October 1981, the constituent parliament, consisting of the National Security Council (the upper house) and the Advisory Council, consisting of 160 members appointed by the generals, began its work. A draft of a new constitution was prepared, and adopted by referendum in November 1982.

Evren was elected president for a seven year term following a national referendum. The new constitution provided him with the right to dissolve the parliament, to declare martial law, appoint senior officials of the executive and legislative branches, and to chair sessions of the National Security Council.

In preparation for the vote, the generals subjected the new parties and their programs to strict military oversight, checking for compliance with the provisions of the newly-established laws. Only three parties – the Motherland Party, the Populist Party (the effective successor of the CHP), and the National Democratic Party, led by retired General Turgut Sunalp, were allowed to participate. The Motherland Party won a majority, and formed a government.

For the remainder of the decade, more parties were allowed to form, most of them successors to parties or movements which existed earlier. In 1987, the ban on former party leaders' participation in politics was lifted, with older leaders soon returning to lead the new parties.

Return to Parliamentary Elections and the Rise of Political Islam

"In 1991, elections resulted in a new coalition between the True Path Party and the Social Democratic People's Party (SHP). However, a split within the coalition led to the victory of the Islamist Welfare Party in elections in December 1995. Shortly after the collapse of the coalition, the SHP broke up, with the CHP recreated, presenting itself as the party of Ataturk's principles. The government crisis lasted until June 1996, when the Welfare Party and Truth Path Party managed to form a [short-lived] coalition."

"From this moment, the influence of the Welfare Party began to grow, and its leader Necmettin Erbakan began to take steps to limit 'excessive Western influence'."

"His attempts to improve relations with Libya and Iran, and the proposal by his assistant Abdullah Gul to create a common Islamic market and an Islamic customs union displeased the military elite. At a meeting of the National Security Council on February 28, 1997, it was recommended that the government ban the Welfare Party as a threat to the secular regime…On February 22, 1998, the Constitutional Court ordered the dissolution of the party. Erbakan was prohibited from political activity for five years."

"Elections in 2002 resulted in the coming to power of the ideological heir to Erbakan's party – the Justice and Development Party (AKP), led by Abdullah Gul, which declared the AKP to be the party of moderate Islam." In 2003, Recep Tayyip Erdogan succeeded Gul as Prime Minister.

2007-2010: Purge After Purge for the Military

In April 2007, the AKP nominated Gul for the post of president. The military elite was highly sensitive to the prospect of the Islamists capturing both the prime minister's office and the presidency.

"Under pressure from the military, Erdogan promised to propose a compromise candidate, but at the last moment changed his mind and agreed to the re-nomination of Gul, demonstrating to members of his party…that it is possible to withstand pressures from the military and the secular elites." Following a lengthy deadlock, a simple majority vote the parliament on August 28 confirmed Gul as president.

In June 2007, a public scandal broke out over the theft of military equipment and ammunition by retired military personnel. In the course of the investigation, it was soon said that a secretive organization dubbed 'Ergenekon' — a secular ultranationalist organization with deep ties to the military, used assassinations, kidnapping, and blackmail to try to topple the government.

The summer of 2007 saw the first wave of arrests against suspected members of the group; several retired military officers, criminal leaders, businessmen and journalists were arrested. In the winter of 2008, another wave of high-profile arrests took place, this time involving dozens of suspects including serving high-ranking generals and officers, prominent journalists, public figures and politicians.

In March 2008, Turkey's General Prosecutor asked the Constitutional Court to ban the AKP for undermining the foundations of secularism; the court refused.

"On the one hand," Vasilyev recalled, "this decision helped to avoid a government crisis, military intervention and a worsening economic situation. On the other hand, the AKP leadership demonstrated that it could withstand pressure from the military. Some observers linked the Constitutional Court's decision with the new arrests in the Ergenekon case, which took place on the eve of the Court's deliberations."

The court proceedings 'discovered' illicit arms trafficking, army participation in political repressions against ethnic and religious minorities, and documents showing plans for a military coup against the ruling AKP government going back to 2003. Critics of the trials pointed to numerous procedural violations and inconsistencies in the accusers' allegations.

In early 2010, the Istanbul Prosecutor's Office began a massive case against generals and admirals accused of planning a 2003 military coup dubbed 'Sledgehammer' to oust the newly elected AKP government. 325 people, mostly military officers, were convicted.

Ultimately, "as a result of the Ergenekon and Sledgehammer efforts, the Turkish military lost about 17% of its officer corps, resulting in great damage to the combat capabilities of the Turkish army." In June 2014, 234 of the officers were released after a court found numerous violations of legal norms and evidence proven to be untrustworthy.

Ultimately, the excerpt noted, "the generals did not forget or forgive the shaming they faced during the trials" carried out between 2007 and 2010. "In the context of the growing social, military, political and economic instability in Turkey, the officers saw a chance to return to power and to do away with the hated party and government."

On July 15, 2016, they took their chance. However, in contrast to the military interventions of 1960, 1971, 1980 and 1997, the officers failed. Apparently, the AKP's efforts to purge the military and to remove it from its long-standing role as guarantor of Turkish secularism had proven successful, at least for the time being.