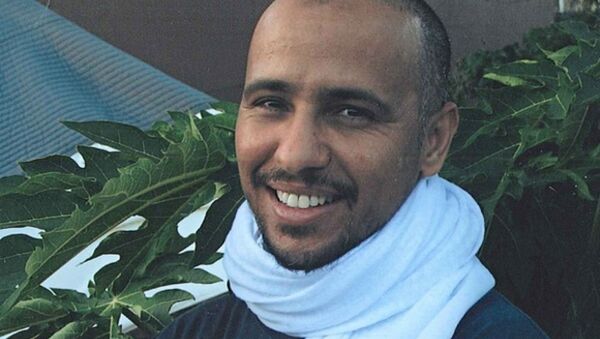

"I feel grateful and indebted to the people who have stood by me," Slahi said on the day of his release, in a statement from the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), which represented him. "I have come to learn that goodness is transnational, transcultural, and trans-ethnic. I'm thrilled to reunite with my family."

Slahi, 45, was detained in Mauritania at the behest of the United States in 2001, and transferred to Guantánamo Bay in 2002. He had fought with al-Qaeda in Afghanistan in the early 1990s when the group was part of the anti-communist forces supported by the US government. He subsequently broke ties with the group, left Afghanistan, and worked for several years as an engineer in Germany, returning to Mauritania in 2001, according to the ACLU.

During the period covering the over-14 years of his detention, Slahi was never charged with any crime. He was accused of helping recruit terrorists for the 9/11 attacks and of plotting an attack on the Los Angeles airport, allegations for which his lawyers say there is scant evidence. Indeed, a federal judge ruled in 2010 that "there was no basis for the government’s contention that Mr. Slahi was part of al-Qaeda and thus ruled that he could not be detained indefinitely," an ACLU statement in 2015 explained. Slahi was finally cleared for release in July.

In his New York Times bestselling book "Guantánamo Diary," Slahi describes his experience in the American rendition and torture program, including a "world tour" of international torture dens. He detailed the sleep deprivation, sexual humiliation and threats to his family that he suffered, as well as various "interrogation techniques," including beatings, immersion in ice and being forced to drink salt water. He also depicts the relationships that developed while he was imprisoned, particularly with his guards, and acknowledges their humanity as well as that of his fellow detainees.

"We are overjoyed for Mohamedou and his family, and his release brings the US one man closer to ending the travesty that is Guantánamo," Hina Shamsi, one of Slahi's attorneys and director of the ACLU’s National Security Project, said in the ACLU statement on his release.

"Dozens of other men still remain trapped in Guantánamo. With time running out, President Obama must double down and not just close the prison, but end the unlawful practice of indefinite detention that it represents."

Slahi plans to continue writing and perhaps open a small business using the computer skills he learned in prison, according to a report by The Intercept on his release.

Sixty prisoners remain at Guantánamo Bay.