On Tuesday, asked to explain what Deputy Foreign Minister Sergei Rybakov meant when he said that Russia was prepared to introduce "asymmetrical measures" if the US introduces new tough sanctions against Russia, Lavrov indicated that it meant exactly what it sounded like – that Russia will "definitely respond if there are new sanctions."

"First we will see what happens with the plans of our US colleagues, who issue threats, but at the same time continue to talk to us," Lavrov added.

The deputy foreign minister did not specify what specific measures he had in mind, but did recall Russia's recent decision to suspend the Russian-US agreement on the disposal of weapons-grade plutonium. That deal, signed in 2000, stipulated that the two countries were obliged to dispose of 34 tons of weapons-grade plutonium by burning it in nuclear reactors, beginning in 2018. Russia has all the necessary infrastructure to dispose of the plutonium under this deal, while the US does not.

Russia outlined several conditions for the renewal of the plutonium agreement, including a reduction of the US troop presence and military infrastructure in NATO countries bordering Russia, and the abandonment of all anti-Russian sanctions, from the Magnitsky Act to measures taken by the US and its allies over alleged Russian interference in the Ukrainian crisis. Rybakov recognized that the Obama administration is unlikely to agree to these conditions. "In this case, the agreement will be suspended indefinitely," he said.

The US is also heavily dependent on Russia in another area of the nuclear sector: for the supply of enriched uranium. Former deputy director of the Russian Research Institute of Nuclear Engineering Igor Ostretsov recently told the online newspaper Svobodnaya Pressa that the US presently has almost no uranium enrichment capacity for the supply of fuel to its nuclear power plants; existing US technology is severely outdated, he said.

Earlier this year, the US even halted the construction of a centrifuge enrichment plant, its engineers proving unable to master the technology. Meanwhile, Rosatom's share of the global uranium enrichment market continues to grow, and is expected to account for 45-50% of global production by 2020, according to the World Nuclear Association.

"Many say that the US wants to destroy Russia. That's nonsense," Ostretsov said, adding that "the collapse of Russia would lead to the immediate collapse of the United States, because the US nuclear industry works on uranium enriched in Russia."

Military cooperation includes things like the plutonium agreement. "With regard to foreign policy, it must first be said that we were not the ones to initiate the deterioration in relations. The US tore up cooperation in many areas themselves. But we have begun to approach US proposals more critically. Our partners very much enjoyed using our capabilities without offering anything in return. We can stop accommodating them on issues of interest to them. This includes issues related to Afghanistan, the Arctic, and so on."

In 2015, Zhuravlev recalled, the Russian government effectively closed off access to the airbase in Ulyanovsk, which the US had previously used to supply their troops in Afghanistan. "In the future, we can continue to refuse this kind of cooperation."

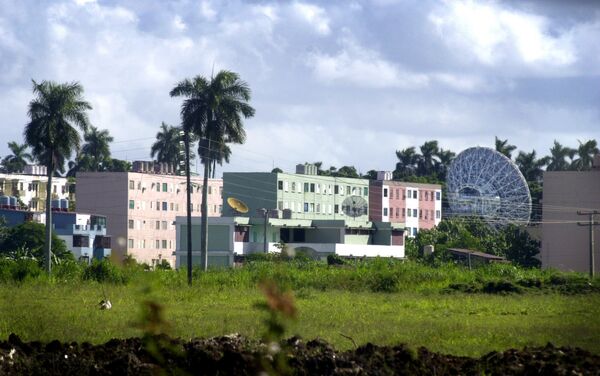

"Take one more example: for a long time we did not want to reopen the long-shuttered SIGINT radar center in Lourdes, Cuba. Now, it's possible that we will be doing so. During his recent trip to Latin America, President Putin said that we do not want to have military facilities in the region, and that's true. But if the US forces us to play hard, we'll have to do so."

Space cooperation is another important area, the analyst noted, and includes not only the RD-series rockets, but questions concerning the International Space Station as well.

"How is it that we invested 75% into the ISS, but own 25%, while for the US it's just the opposite? At the time of the station's construction, the US had no meaningful experience in creating manned orbital stations. Only the USSR had this experience. The means to deliver cargo and astronauts to the ISS are ours; so are the station's technologies. The US was developing their space program along different lines, and ended up being mistaken. It has turned out that at this stage, their program is not working. But somehow the lion's share of the ISS belongs not to us, but to the US and its allies."

"Until this moment, we have not raised this question, because we did not seek confrontation. But if that's what the US wants, we will have no choice, and begin to discuss this issue as well. I'm not talking about closing the ISS, but it will be necessary to revise the legal norms and decide who owns what."

Zhuravlev stressed that ultimately, the escalation of tensions cannot continue endlessly, and that hopefully, the next administration, if not this one, can "go a different path – can begin looking for solutions, negotiating; this is especially true considering that we're not asking for much."

"Escalation cannot be infinite. None of us wants to unleash a nuclear war; and no missile defense system will be able to change anything. If we wanted to create a world where nothing but cockroaches survived, it would be enough to detonate our nuclear stockpiles on our own territory. Therefore, sooner or later, tensions will have to be reduced, and we will have to negotiate."

Andrei Martynov, director of the International Institute of Newest States, suggested that whatever Russia's response to US sanctions might be, it will be asymmetrical, with the recent ultimatum on the processing of weapons-grade plutonium being a good example.

As for Europe, the analyst noted that it's highly unlikely that they will follow the US down the path to more sanctions. "I'm pretty sure that the EU will end these ridiculous sanctions in the near future. This has already been spoken aloud, not just by businessmen, but by high-level European bureaucrats as well. Just last week, [EU foreign policy chief] Federica Mogherini said that it was time to reconsider Brussels' approach, because so far it has led to nothing but losses. Russian experts talked about this earlier, but underestimated the degree to which the EU leadership depends on their overseas partners."

Removing sanctions is "mandatory," Fallico stressed. "It's not a choice, but a necessity." "I'll put it this way; Europe can afford to maintain sanctions for another year, the US – for three."

Ultimately, as far as Washington's idea for more sanctions is concerned, Martynov suggested that perhaps it will take a difficult domestic political crisis connected to the current elections "for the US to sober up and see common sense prevail."