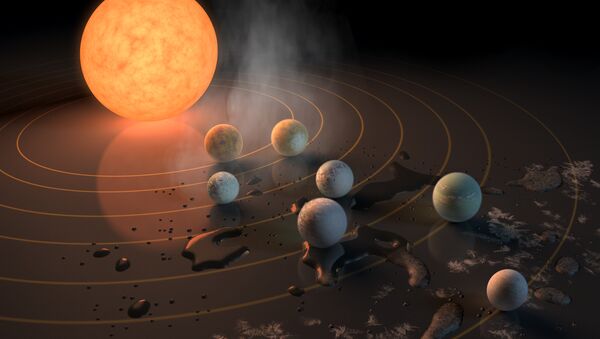

On Wednesday, NASA announced the discovery of at least seven Earth- and Venus-sized exoplanets orbiting a star known as TRAPPIST-1, some of which present the conditions for life.

TRAPPIST-1 is an ultra-cool dwarf star with a radius slightly larger than Jupiter's, located approximately 40 light-years (378.4 trillion km) away from Earth in the constellation Aquarius.

Astrophysicist Jeremy Leconte of the University of Bordeaux, co-author of the study about the planets which was published in Nature on Thursday, told Radio Sputnik that the scientists first noticed at least two planets orbiting TRAPPIST-1 in September 2015.

Leconte said that the density of the planets suggests that they are rocky, and some of them may have less dense materials such as water.

"In the very near future, we're going to know more about the atmospheres; because they are (orbiting) around a very tiny star, it's easier for us to pick out the signal of the atmosphere. Maybe in the very near future we will be able to know what the atmosphere is made of," Leconte explained.

The four outer planets might also be able to maintain liquid water, which is thought to be key to life, if their atmospheres are thick enough to trap heat.

"At the moment, we don't know if there is water. We know that there could be water, meaning that if there is H2O there, the conditions make it possible for this water to be liquid. That's an interesting thing. We think that if there is liquid water, and other stuff, that life as we know it (can) emerge."

The first exoplanet was discovered orbiting a pulsar in 1992, and in 1995 scientists discovered 51 Pegasi B, the first exoplanet found orbiting a star similar to the Sun.

In recent years, the rate of discovery has increased rapidly: in May 2016 NASA announced that its Kepler space telescope had discovered 1,284 exoplanets and as of February 22, 2017, astronomers have identified 3,583.

Leconte said that scientists have had more success because they widened their search for exoplanets. Some luck is required, because the planet needs to transit in front of its star at the right time in order to be spotted by telescopes.

"Now, we are looking for planets in places where we didn't before and where we couldn't before. That's how we came to the discovery of TRAPPIST-1, because the type of star that we are looking at, these very tiny red stars, these are not the targets we were looking at a decade ago. That's why now it's becoming easier to detect these planets, but you still need a lot of luck."

Earlier this month, German astrophysicists proposed a variation of the project which uses a solar-powered light sail and travels at 4.6 percent of the speed of light.

Leconte said that scientists have the knowledge to plan a trip to TRAPPIST-1, but such an undertaking requires the political will to do so.

"Forty light years, it means that if we go at ten percent of the speed of light it will take at least 400 years to go there, so it's going to be a long trip. But, when are we going launch? The limitation now is not so much the science," Leconte said.

"I think we may be more ready to launch something like that then we were when we announced that we would go to the Moon. But now, it's a question of politics and money, unfortunately. Do we want to do that, and if we want to, we just need to put the means to try it and the technology will follow."

Have you heard the news? Sign up to our Telegram channel and we'll keep you up to speed!