The February 1917 Revolution, which began on March 8 (February 23 according to the Julian calendar used by the Russian Empire), lasted about a week, and ended in the abdication of Czar Nicholas II, the end of Czarism, the collapse of the Russian Empire and the establishment of the Provisional Government, which attempted to concentrate all legislative and executive authority in its hands.

In Poland, Zasorin recalled, "some historians and politicians say in a linear manner that Polish sovereignty was artificially provoked by the revolutionary crisis, first in February and then in October 1917. Their opponents are convinced that Poland was already objectively and firmly marching toward independence from Russia since at least the end of the nineteenth century; therefore, they say, the upheaval facing Russia at the start of the 20th century had no effect on this process."

"What is the truth? Perhaps, as always, somewhere in the middle," the historian noted. "In our understanding of this historical problem, I would like to caution against simplistic and extreme conclusions."

But it was during the revolutionary spring of 1917 that the Polish question gained a new strength, the historian added. "After February, the national separatist movement started to be revitalized, and a Polish national elite gained political weight. In the conditions of the liberalization of the political regime, an expansion of rights and freedoms for Russian citizens, the Polish elite saw an intensification of the desire for political independence."

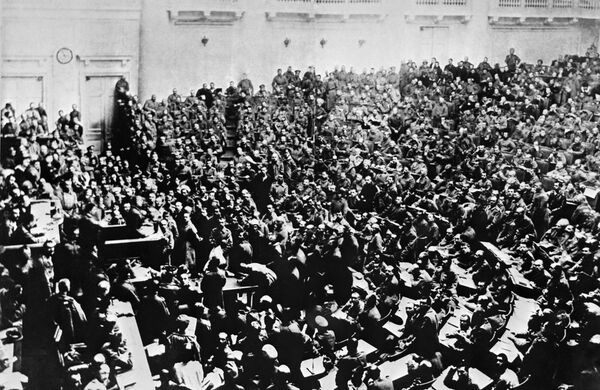

It's worth keeping in mind, Zasorin recalled, that the end of Czarism was complemented by the tremendous uncertainty in the political situation in Russia, thanks to the phenomenon of dual power – with two competing centers of power set up in Petrograd after the February Revolution – the Provisional Government and the Petrograd Soviet.

"The Polish question," the historian noted, "became the subject of a kind of political competition between the two all-Russian centers of power. In fact, both of them, seeking to demonstrate their democratic character, flirted with the most significant national minorities, hoping either for their support in the struggle for political power, or looking for approval from Russia's Entente allies, using the issue of Polish sovereignty as ammunition."

At first, the Provisional Government favored the preservation of the unity of the Russian state, hoping that the formal provision of equal civil rights and freedoms would slake national minorities' thirst for national recognition. The liberal parties which dominated the government, including the Cadets and Octoberists, each considered it possible to provide Poland with autonomy, but not independence.

The resolution adopted by the Petrograd Soviet, read as follows: "The Petrograd Soviet of Workers' and Soldiers' Deputies declares that Russian democracy stands for the recognition of national-political self-determination of peoples, and proclaims that Poland has the right to complete independence in national and international affairs. We send our fraternal greetings to the Polish people and wish it success in the forthcoming struggle for the establishment of a democratic, republican order in independent Poland."

This appeal, Zasorin noted, led to an immediate radicalization of the position of the Provisional Government as well. On March 16, 1917, they issued their own Proclamation "to the Poles," and also promised independence – including all three sections of the country divided by the Third Partition.

"This official statement would play a fatal role in the subsequent evolution of the state, and set in motion the process of the disintegration of the empire," Zasorin noted. "In the summer of 197, Finland declared independence, rumblings started in Ukraine about self-determination, and the pace of disintegration only quickened after that. All this led to an internal split within the Provisional Government. When the centrifugal effect turned from the Polish to the Ukrainian question, the Cadets and Octoberists were frightened, leading to their insoluble conflict with the SRs and the collapse of the coalition in July 1917."

"It is significant," the historian added, "that the last Russian Czar himself already tried to play the 'Polish card'. In December 1916, Supreme Commander Nicholas II appealed to the Army and Navy with Order 870, which among the aims of continuing the war first mentioned 'the creation of a free Poland.' Interestingly, this would be the first and last time that the Czar or other royal dignitaries would say anything about the matter. But the words in the Order are also a matter of historical fact, from which it is possible, if desired, to create an argument about a fundamental change in the Czarist position on the Polish question shortly before the revolution, and at a critical moment in the First World War."

In truth, of course, "the late pre-revolutionary and post-revolutionary Russian authorities abandoned their prerogative for control over Poland not for ideological reasons, but primarily because Polish territories had been occupied by the Central Powers in 1915, and Russia had physically lost this right." In fact, Zasorin noted, "in the competition for Polish sympathies, Russia left Germany and Austro-Hungary far behind."

The altered Russian position, the historian wrote, helped lead to the decision by future Polish Second Republic leader Josef Pilsudski, then commandant of the Polish Legions under the Austro-Hungarian Empire, to disband his units in the summer of 1917.

The Polish Lancers, furthermore, gained the right not to swear an oath of allegiance to Russia, using their own text instead, which spoke about the independence and unification of Poland. Zasorin recalled that "at an April 1917 Congress of Soldiers in Kiev, [the Poles] adopted a declaration proclaiming that the continuation of the war was aimed at the restoration of Polish independence on all [occupied] lands. On this basis, it was planned to create a Polish army that would fight on the side of the Entente."

These plans suited the interests of the Provisional Government perfectly well, the historian added. "In March 1917, Minister of War Alexander Guchkov developed a plan on the formation of a Polish Army on Russian territory, providing for the provision of the Polish Division with artillery and engineering units, the creation of a second division, and their eventual unification into a corps. To this end, the Russian General Staff established a military commission for the formation of Polish units. On April 30, the commander of the Polish Infantry Division, Major-General Tadeusz Bylewski, became head this unit."

Ultimately, Zasorin noted, "by the spring and summer of 1917, Poland's drive for independence was greatly stimulated by the democratization processes occurring in Russia, and by the political chaos and inefficiency of the new Russian authorities, the collapse of the army and constant setbacks at the front."

In late 1917, February gave way to October, leading to the collapse of the disorganized and exhausted Provisional Government and the seizure of state power by the Bolsheviks and their allies, who soon proclaimed the world's first socialist state.

As for Poland, the country gradually reemerged as a sovereign republic between 1917 and 1918, and the Second Polish Republic was formally established on November 11, 1918, 123 years after the Third Partition, at the close of the First World War.