The habitable zone is the distance from a star required by a planet to support liquid water. Too close to a star and the heat will only allow water to exist as vapor (such is the case for Mercury and Venus) while too far away and the water will freeze (Jupiter and the other gas giants are in this category, although without a rocky surface they are not thought to be able to support Earth-like life.) For celestial bodies orbiting our Sun, Earth, Mars, and the dwarf planet Ceres are in the habitable zone.

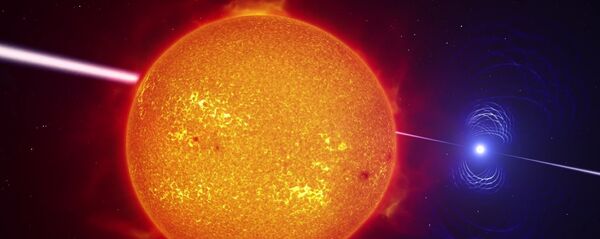

TRAPPIST-1, a red dwarf star with seven Earth-like planets in orbit, has three in its habitable zone: 1e, 1f, and 1g. The planets 1a and 1b likely once had water that has since evaporated, while 1c has a long-shot chance at liquid water in a thin sliver on its surface.

But the most mysterious of these worlds is TRAPPIST-1h, the farthest from the star. According to the Cornell team, hydrogen volcanoes could outpace the escape of hydrogen gas from 1h's atmosphere and that gas could then presumably take liquid form, allowing for life.

The Cornell team ran a simulation to see how large a habitable zone can be, assuming that planets are covered in hydrogen-rich volcanoes. They found that volcanic hydrogen could increase the habitable zone's reach by as much as 60 percent.

"Our volcanic-hydrogen habitable zone is different, because so long as volcanism is intense enough, it can outpace the rate at which hydrogen escapes into space," lead author Ramses Ramirez, a Cornell research associate, wrote in an email to Space.com. He added that while 1h was just outside the volcanic hydrogen habitable zone, "it is really close." If the planet was only slightly more volcanic than the models indicate, then 1h could be habitable.

There are many additional factors at work to determine a planet's habitability. Mars has plenty of volcanoes, but only trace amounts of hydrogen remain in its atmosphere. Eons ago, hydrogen gas escaped Mars' thin atmosphere and left the planet dry and lifeless.

Some theories hold that early Earth had a high quantity of hydrogen gas in its atmosphere. Hydrogen atoms are promiscuous, bonding freely with whatever is available. In modern times, Earth's hydrogen lies on and below the surface in the form of water.

But TRAPPIST-1's worlds are very young themselves, some 4-billion years younger than Earth. If Ramirez's theory holds true, then a young world with a hydrogen-rich atmosphere may one day be watery and temperate, similar to the Earth.

Little information is available about the atmospheres of TRAPPIST-1's planets, as existing telescopes are not powerful enough to study them. Future telescopes, like NASA's James Webb Space Telescope (set to launch in 2018) and the ESA's European Extremely Large Telescope (2024) should shed more light on this matter.

These telescopes will also search for other "biosignature" gases like oxygen and methane. Although they are no guarantee of life, the presence of these gases would be an excellent clue. Ramirez added that volcanic planets tend to have thicker, "puffier" atmospheres that are easier to study. "Biosignatures would be easier to detect in these hydrogen-rich atmospheres," he said.