A variety of companies, including Google, SpaceX, Boeing and Samsung, are vying to launch global broadband networks via the deployment of thousands of micro satellites into low orbit. The first launches are planned for 2018.

However, a team of Southampton University researchers, led by Dr. Hugh Lewis, senior lecturer in aerospace engineering, have concluded the results could well be calamitous. The group ran a 200-year simulation to assess possible consequences of such a rise in orbital traffic, concluding it could create a 50 percent increase in the number of catastrophic satellite collisions.

Microsatellites, megaconstellations & strategies for combatting increasing volumes of #spacedebris https://t.co/WBOi0gz4iW #SpaceDebris2017 pic.twitter.com/6USZxxHoma

— DLR — English (@DLR_en) April 18, 2017

Such crashes would likely produce a further increase in the amount of space junk orbiting the Earth, raising the prospect of further collisions and potential damage to the services the satellites were intended to provide.

"The constellations that are due to be deployed from next year contain an unprecedented number of satellites, and a constellation launched without much thought will see a significant impact on the space environment because of the increased rate of collisions that might occur," Dr. Lewis said.

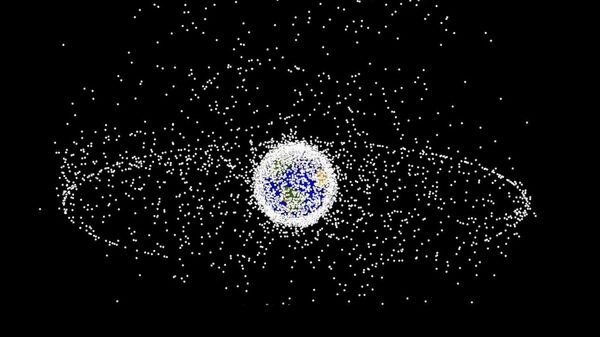

With approximately 750,000 objects larger than one centimeter orbiting Earth, junk surrounding the planet is already a major obstacle to attempts to explore space. At average speeds of 40,000 kilometers per hour, impacts on space hardware would deliver roughly the energy equivalent to the explosion of a hand grenade, with potentially dramatic consequences for operational satellites.

Transforming the silent movement of 27000 pieces of space junk into sound — by @ProjectAdrift #spacedebris2017 https://t.co/Ela89WLnt9

— ESA Operations (@esaoperations) April 18, 2017

The team's research was funded by the European Space Agency, which is now calling for all satellites planned for orbital mega-constellations to be able to move to low altitudes once their missions are over, so they burn up in Earth's atmosphere. The ESA state they should also be able discharge all batteries, fuel tanks and pressure tanks to prevent explosions that would scatter debris.

Dr. Holger Krag, head of the Agency's space debris office, said many companies proposing to launch services provided by such mega constellations lacked experience of the difficulties of working in Earth's orbit.

Moreover, Dr. Krag expressed concern at ambitions to manufacture satellites at a fraction of the cost and many times the rate of traditional taxpayer-funded spacecraft, while still meeting exacting guidelines for their post-mission disposal.

"Right now, under all the taxpayer-funded space flight we are doing today is only able to achieve 60 percent of success rate for that maneuver. How can they be better under commercial pressure and with cheaper satellites? That's the worry we have," he said.

Dr. Lewis is to present his research at the ESA center in Darmsadt, Germany, where some of the aspirant private space explorers will also be in attendance.

"Even with good intentions it remains an extremely high technological challenge to manage to [meet ESA proposals]. Let them achieve a success rate of 90 percent, which would be extremely good compared with what we do now, and it still means a few hundred satellites will be lost and at that altitude it's not good. It's as simple as that," Dr. Krag concluded.

Exacerbating the situation, Dr. Lewis believes, is a lack of a dedicated international body dealing with the issue of space junk.

"Junk is dangerous. While some will de-orbit naturally after 5-10 years, some will drift indefinitely. Disposal isn't easy either — even to get a ship into orbit is very costly, and then there's the issue of securing the junk in space before you can even consider getting rid of it," Dr. Lewis told Sputnik.

However, he adds that research into these issues is significant and ongoing — the end result could be spacecraft equipped with retrieval solutions similar to those seen in science fiction movies. Another option is "in-orbit" servicing, which would mean satellites could be upgraded and repaired in space — meaning few if any satellites will be reduced to junk status.

"In-orbit servicing is the next big thing. However, there are a number of challenges to achieving that goal — and another issue is upgrading old satellites that aren't equipped for updates. It's difficult to interact with an object that is not prepared for it. We need to ensure in our quest to clean up the junk that we don't add more and make the problem worse."