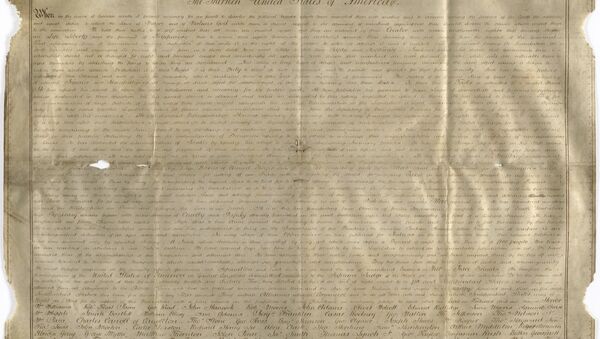

A Harvard University research pair announced on Friday that they'd discovered only the second parchment manuscript copy of the pivotal document in a small provincial records office in Chichester, southern England. (Until now, the only known parchment copy was the 1776 document preserved in the National Archives in Washington, DC.)

It is now the only other known 18th century, handwritten copy of the document that formally launched the bloody separation of the American colonies from England.

The discovery began with a short listing from the catalog of the West Sussex Record Office, which read, "Manuscript copy, on parchment, of the Declaration in Congress of the thirteen United States of America.

The listing caught the eye of Emily Sneff, a researcher with Harvard's Declaration Resources Project, in August 2015. She told the Harvard Gazette she didn't think much of it at first, but the words "manuscript on parchment" intrigued her.

After seeing images of the document sent by the English archive, Sneff and fellow Harvard researcher, professor of government Danielle Allen, would come to realize that they had a very, very significant find on their hands.

The new discovery, which the team is calling the Sussex Declaration, isn't an official government document, but a display copy commissioned sometime in the 1780s, the researchers say. They believe it was probably commissioned by one of the drafters of the US Constitution, James Wilson of Pennsylvania, who would go on to be one of the young United States' first Supreme Court Justices. How it got to England remains a mystery, but the copy is believed to have ended up in the hands of Charles Lennox, third duke of Richmond, who was known as the "radical duke" for his support of American colonists during the Revolutionary War, the Boston Globe reports.

A notable difference between this parchment copy of the declaration and the official government document is the order of names. In the official document, the names of the signers are grouped by state. In this copy, however, the order is deliberately jumbled.

"The team hypothesizes that this detail supported efforts, made by Wilson and his allies during the Constitutional Convention and ratification process, to argue that the authority of the Declaration rested on a unitary national people, and not on a federation of states,'' Sneff and Allen wrote in the statement.

Allen explained to the Harvard Gazette that one of the major political debates of the early days of the new American union was whether it rested on the authority of the people or the authority of the states.

"[T]he Sussex Declaration scrambles the names so they are no longer grouped by state," Allen said. "It is the only version of the Declaration that does that, with the exception of an engraving from 1836 that derives from it. This is really a symbolic way of saying we are all one people, or ‘one community,' to quote James Wilson."