Following NASA's announcement, postdoctoral student Sebastiaan Krijt with the University of Chicago posed a question: if life formed on one of the TRAPPIST worlds, could it spread to the others via space debris?

Krijt's findings, published in Astrophysical Journal Letters, were that simple life forms could travel between the TRAPPIST worlds on the backs of debris kicked up by asteroids or comets.

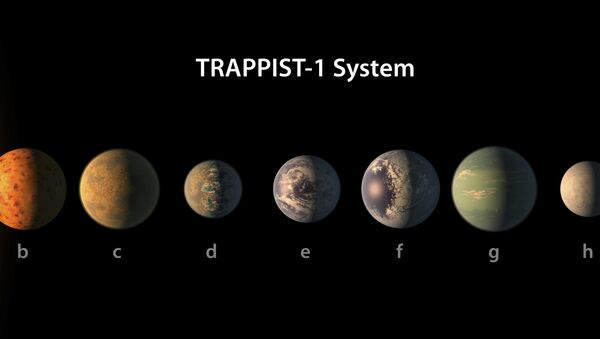

TRAPPIST-1 is a supercool dwarf star, and all seven of its planets orbit it very closely. TRAPPIST-1b, the closest planet, is just over 1 million miles from its star, while the farthest world, TRAPPIST-1h, is about 5.8 million miles away. For comparison's sake, Mercury is about 36 million miles away from our sun.

And since the TRAPPIST-1 worlds are all very close to the star they orbit, that also means they're very close together. "Frequent material exchange between adjacent planets in the tightly packed TRAPPIST-1 system appears likely," said Krijt in a statement. "If any of those materials contained life, it's possible they could inoculate another planet with life."

Imagine, for a moment, TRAPPIST-1e: a world teeming with life. An asteroid strikes 1e, kicking up not just a cloud of dust, but large chunks of the planet out of the thin atmosphere and into space. This material takes a short journey through space before it collides with TRAPPIST-1f, the next planet over. And if this chunk contains simple life, that would make the bacterial hitchhikers a multiplanetary species – something humanity still has yet to achieve.

This is far from likely to happen: first, life must form on one of the TRAPPIST worlds. Then, a large planetoid must collide with that world, expelling matter that has life on it into space. The material must move fast enough to escape the planet's gravitational pull, but not so fast as to kill the life on it. Then it has to collide with another TRAPPIST planet in short order, or else it'll die in the vacuum.

Unlikely, but according to Krijt, not impossible. His team ran simulations on TRAPPIST-1 and found that this process could occur in just a 10-year period. In the case of a collision, ejected mass would be in the "sweet spot" of velocities fast enough to escape the planet but not so fast as to kill theoretical life forms.

Space debris is more abundant than you might imagine. The Chicago team estimated that 40,000 tons of it hits Earth every year – but as the only large object close to Earth is our barren and lifeless moon, none of it is likely to carry life. "Material from Earth must be floating around out there, too, and it's conceivable that some of it might be carrying life. Some forms of life are very robust and could survive space travel," said University of Chicago Geophysical Sciences professor and paper co-author Fred Ciesla.

"Given that tightly packed planetary systems are being detected more frequently, this research will make us rethink what we expect to find in terms of habitable planets and the transfer of life – not only in the TRAPPIST-1 system, but elsewhere. We should be thinking in terms of systems of planets as a whole, and how they interact, rather than in terms of individual planets."

Even if TRAPPIST-1 is devoid of life, Ciesla says that his team's research has bearing on other similar systems to TRAPPIST-1 to be discovered in the future. "The relatively new field of exoplanetology is exploding and being considered more seriously than ever," he said. "If we took the solar system as a model, we could never have imagined the things we're finding, such as the recent discovery of a planet that orbits two suns."