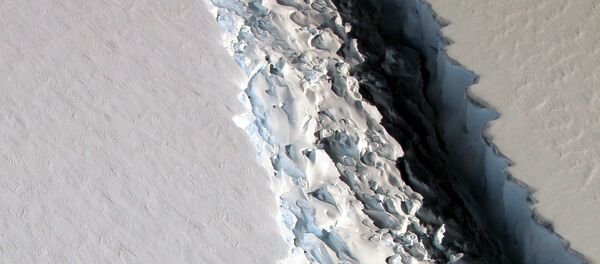

When the crack was first observed in mid-2016, it was a tiny silver. But in November, it started to grow with impressive rapidity. It was thought to be all-but-certain than an iceberg consisting of 9 to 13 percent of the 19,000 square mile ice shelf's mass would form in 2017.

After a few months of inactivity, the crack accelerated once more, growing more than 10 miles in less than a week. Only 8 miles separate the 125-mile long crack from the edge of the shelf.

The 1,900 square miles will be the third largest iceberg ever recorded when it breaks up, but it isn't likely to last for more than a few years before breaking apart and sinking into the ocean.

UK-based Project MIDAS (Melt on Ice Shelf Dynamics and Stability) has been leading the monitoring of Larsen C. "The rift tip appears also to have turned significantly towards the ice front, indicating that the time of calving is probably very close," wrote Dr. Adrian Luckman, a professor of glaciology at Swansea University and the project lead, on the MIDAS blog. "There appears to be very little to prevent the iceberg from breaking away completely."

Larsens A and B broke off in 1995 and 2002 respectively, but Larsen C is significantly larger than either of them. As only a chunk of Larsen C is going to break off, the shelf itself will survive — probably.

Since ice shelves float on top of the water, them breaking apart cannot raise sea levels (just as ice melting in a cup of water doesn't raise the water levels) but it can hasten the release of glaciers held in by the ice shelves, which can lead to sea level rise. In the case of a piece of ice as large as Larsen C, global sea levels may rise by as much as four inches.

Modelling suggests that the loss of this chunk could cause the entire ice shelf to be destabilized and break apart. This would send a chink of ice the size of Costa Rica into the sea.

Since the 1950s, when monitoring began, the Larsen Ice Shelf has warmed by nearly 3 degrees Celsius.