Last week, Commodore Paul Burke, the head of operations under the recently formed Director General Nuclear organization, responsible for Britain's nuclear submarines, told Sputnik that Russia's hypersonic weapons should be subjected to international norms and rules.

"Any weapons system should actually commit to some international norms and some regulations, absolutely," Burke said, speaking to reporters on the sidelines of the STRATCOM Deterrence Symposium in Omaha, Nebraska. "It should definitely be under some international regulations," he added.

"We'll keep an eye on what they're doing, and try to respond accordingly through diplomatic, international norms and treaty obligations. The UK wouldn't be able to do anything like that. So, we wouldn't be able to develop that sort of system ourselves," Burke noted.

The officer's commentary on the need to regulate Russian hypersonic weapons was simply brilliant, according to independent military analyst Vladimir Tuchkov, since it is in effect a polite way of saying that "since we aren't capable of doing anything ourselves, it's necessary to tie Russia down hand and foot."

What's even more surprising, the analyst wrote, is that Commodore Burke's proposal did not meet any push-back from the UK's US ally. On first analysis, this might seem strange, Tuchkov noted.

"After all, the US has announced their own major successes in the development of hypersonic weapons for quite some time now. Very large financial and intellectual resources have been invested in a series of programs for missiles to achieve supersonic speeds. Nevertheless, they did not say anything when the proposal was made to put such developments under strict international control!"

And while there is the off chance that US policymakers think that these international norms and regulations do not apply to their weapons systems, Tuchkov believes that it is more likely that the silence is an "indirect admission that the US is far behind Russia in this area."

Before going into detail on the state of the Russian and US hypersonic programs, Tuchkov suggested it was worth recalling just how well the US and the UK adhered to these so-called 'international norms' in decades past, when they themselves came to possess fundamentally new weapons technologies.

The analyst recalled, for instance, that when the Royal Navy came to possess its revolutionary Dreadnought battleship technology in 1907, it didn't feel the need to ask the world community permission to build it or use it in combat.

"The US offers even more scandalous examples," Tuchkov added. "They not only pioneered nuclear weapons, but tested them on civilians in two Japanese cities. The Americans also distinguished themselves in Vietnam, with the use of napalm, which not only led to the deaths of millions of people, but to genetic changes" and cancers in the local population "which manifest themselves to this day."

As for the race for hypersonic weapons, here too the US made the first breakthrough. In 1959, American engineers began testing of the experimental X-15 hypersonic rocket-powered plane, a design which would reach speeds of up to Mach 6.5 before the program's closure in 1970. The plane's liquid-propellant-fueled rocket engine severely limited the duration of hypersonic flight, as well as the ability to regulate thrust.

Similar, more prospective research would begin in the Soviet Union a decade later, where starting in the 1970s, the Raduga Construction Bureau began development of the Kh-90 missile. By the late 1980s and early 1990s, it was flying at speeds between Mach 3 and Mach 4. "But in 1991 money for the program ran out, and then the country itself 'ran out' of time, and the project was closed," Tuchkov noted.

"Nevertheless, Raduga developed and implemented a tangible, workable hypersonic scramjet engine. Schematically, it was arranged in approximately the same way as the liquid-propellant rocket engine, but instead of liquid oxygen, the system used atmospheric air entering the combustion chamber through the air intakes."

An even greater breakthrough in hypersonic technology was made by the Baranov Central Institute of Aviation Motor Development. Here, in 1979, engineers began work on the Kholod – an experimental scramjet design project using cryogenic technologies. Using a modified anti-aircraft missile from the S-200 air defense system, engineers created a flying laboratory. That project reached its best results in 1998, reaching a sustained speed of Mach 6.5.

The program's Kholod-2 follow-up, which developers created to reach top speeds to Mach 14, was scrapped in the late 1990s, again due to lack of funds. Its priceless documentation was sold to the US.

It was at this time that the Russian-US "friendship for the ages," including the sharing of Russian secrets to the US defense industry, was concluded, the journalist wrote. The two countries went their separate ways, with the US creating three separate programs, two of them to create unpowered gliders which accelerate to hypersonic speeds during their descent into the atmosphere from suborbital flight.

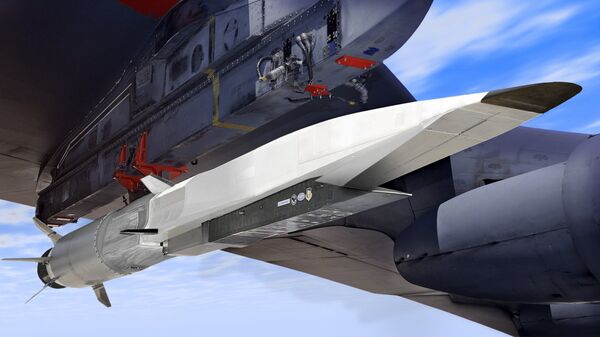

Perhaps the best known US project is the Boeing X-51 WaveRider, an air-launched scramjet aircraft which began testing in 2010, and which has an estimated maximum speed of Mach 5.1 and a range of 740 km.

The Pentagon refers to the X-51 a cruise missile prototype, but according to Tuchkov, this is a bit of a stretch. The journalist recalled that "the main goal of the project is reaching the stable operation of this highly capricious scramjet system." Tests of the X-51 have been carried out with seemingly random success. Where some test prototypes end up landing in their designated target areas, others explode shortly after takeoff, or radically change course in mid-air, forcing engineers to destroy them remotely.

In the case of Russia, the expert noted that here the 3M22 Zircon maneuverable supersonic anti-ship cruise missile is already in the testing phase, and expected to begin deployment aboard Navy ships sometime between 2018 and 2020. Speeding up to Mach 8, the Zircon has an estimated range of between 500-1000 km. Development of an air-launched version of the weapon has been rumored.

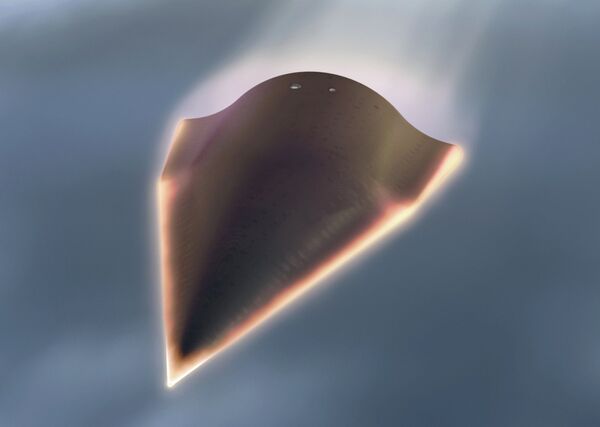

Meanwhile, the US also has two other projects, not based on a scramjet, but also intended to speed up to hypersonic speeds after being launched from near space. These are the Advanced Hypersonic Weapon (AHW) and the DARPA Falcon Project. The former continues its sluggish development, while the latter is believed to have been closed down.

AHW's single successful start in late 2011 saw it reach speeds of Mach 8, although the flight was not maneuverable. A second test in August 2014 ended in failure due to an anomaly in the launch vehicle. Based on publically available information, both projects carry a research nature, and again aren't tied to the creation of specific hypersonic weapons systems.

Meanwhile, in Russia, together with the Zircon, testing of Object 4202, a warhead delivery system developed by NPO Mashinostroyenia, has been underway since 2004. According to various sources, between five and seven test launches have taken place.

Object 4202 is assumed to be faster than the Zircon, various estimates putting its speed between Mach 7 and Mach 12. According to Tuchkov, "each Sarmat missile will be able to launch up to three Object 4202 warheads. Like Zircon, their flight is maneuverable with the help of aerodynamic steering controls at low altitudes, making them difficult to detect by radar. The system has an added layer of stealthiness thanks to a covering of plasma which absorbs radar station signals, preventing their reflection."

"Thus it can be said that work on the creation of Russian and US hypersonic weapons is at varying stages. In Russia, full scale, pre-service trials are underway. In the US, all they have so far is research. Some experts believe the US it at least seven years behind. And this is the real reason why talk has begun about the need to clip Russia's wings" via 'international regulations', Tuchkov concluded.