During his two day visit, Fallon met with Sayyid Badr bin Saud bin Harub Al Busaidi, Oman's Minister Responsible for Defense Affairs, in Muscat. The pair signed a "Memorandum of Understanding and Services Agreement" that secures UK use of naval facilities at Duqm Port — a multi-million dollar joint venture between the two countries.

DefSec strengthens relations with Oman, with new agreement on use of strategically important Port #GlobalBritain https://t.co/Uv5FAJaohg pic.twitter.com/mFEiXaNqgH

— Ministry of Defence (@DefenceHQ) August 28, 2017

An official statement issued by the Foreign & Commonwealth Office said the "booming" Port complex would provide "significant opportunity" for the two countries' "defense, security and prosperity agendas," and serve as a home from home for the UK's flagship aircraft carrier, HMS Queen Elizabeth.

"This agreement ensures British engineering expertise will be involved in developing Duqm as a strategic port for the Middle East, benefiting the Royal Navy and others. Oman is a longstanding British ally and we work closely across diplomatic, economic and security matters. Our commitment to the Duqm project highlights the strength of our relationship," Fallon said.

Radio Silence

The Defense Minister's visit gained virtually no recognition in the UK media — while the traditional paucity of official government business to report on over the summer arguably makes the story a prime candidate for press coverage, radio silence on UK-Oman relations is a seemingly enduring mainstream editorial policy.

Declassified British government files reveal the oil-rich Gulf state's leader Sultan Qaboos bin Said al Said — one of the longest serving unelected rulers in the world — was brought to power in a 1970 palace coup planned by UK foreign intelligence service MI6, and sanctioned by then-Prime Minister Harold Wilson. The Sultan has absolute power in governance, and is also the country's Prime Minister and Minister of Defense, with total authority over Oman's judicial and legal systems.

Ever since the coup, Oman has proven a most faithful ally to the UK, hosting a number of major British intelligence and military operations.

For example, UK spying agency GCHQ has three separate bases in the country — codenamed Timpani Guitar and Clarinet — that feed off various undersea cables passing through the Strait of Hormuz to the Arabian Gulf. In the process, the bases intercept and process a vast volume of emails, telephone calls and web traffic generated in the region, which is then shared with the US' National Security Agency.

Moreover, UK troops have long trained Omani armed forces, and in May 2016 it was announced the UK would increase its number of training teams in Oman from 34 to 45 in 2017.

Oman is the world's biggest military spender by gross domestic product, splashing 16.7 percent of its GDP on the military in 2016 — the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute lists Oman as the world's 23rd largest importer of weapons. The UK provides around a quarter (23 percent) of its exports, and is considered a "priority market" by Westminster.

UK arms exports over the past 20 years have included Piranha armoured vehicles, Challenger-2 tanks, Super Lynx helicopters, Khareef Class corvettes and Typhoon and Hawk combat aircraft.

Agreed in 2013, the Typhoon and Hawk sale was a mammoth deal, totalling US$2.3 billion in value — in announcing the sale, then-Prime Minister David Cameron said the Typhoon had "performed outstandingly" in the 2011 campaign to overthrow Muammar Gaddafi, and it was "no surprise" Oman wished to add the craft to their arsenal as a result.

Perhaps predictably, visits to Oman by UK officials and dignitaries are frequent, with successive defense ministers, members of the Royal Family, Lord Mayors of London and oil company representatives all regularly sojourning to Muscat. Rarely are such visits not used as an opportunity to offer stirring statements of support for Oman's leadership — in February 2014 then-Foreign Office Minister Baroness Warsi praised the Sultan's "wise leadership" — the next year, Chris Breeze, oil giant Shell's country chairman for Oman, said Qaboos had a "clear and inspirational" vision for the country.

East of Suez

The ringing endorsements of Qaboos' leadership offered by the UK's political and industrial elites are far removed from assessments of the country conducted by rights organizations. Their findings are consistent — while Omani repression is not as far-reaching as in other UK-backed monarchies in the region, such as Saudi Arabia and Bahrain, a number of factors are of extreme concern.

"Oman's overly broad laws restrict the rights to freedom of expression, assembly and association. The authorities target peaceful activists, pro-reform bloggers, and government critics using short term arrests and detentions and other forms of harassment. Some detainees arrested since 2011 have allegedly reported that security forces tortured or otherwise ill-treated them," Human Rights Watch notes in its profile of the country.

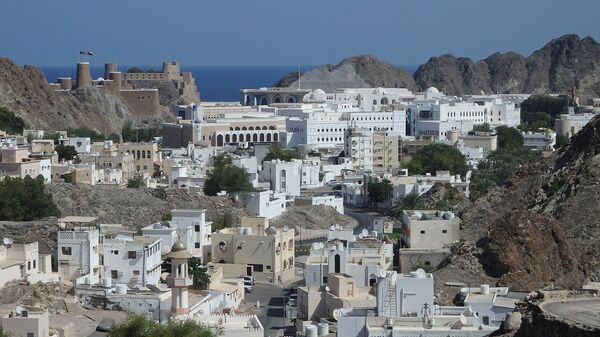

In early 2011, with the "Arab Spring" raging across the Middle East and North Africa, the streets of Muscat were also home to protests. Demonstrators' demands were comparatively humble — they sought political reform, rather than outright revolution.

Many protests were dispersed by brute force, with rubber bullets and tear gas liberally deployed — Khalfan al-Badwawi, a campaigner who fled the country in 2013 after being repeatedly detained by police, has said the UK's military and diplomatic assistance for the Omani government is a "major obstacle" to human rights supporters in the country, and intelligence support from London "propped up" up the Sultan's "dictatorship."

The reasons for the UK's continuing support of the repressive Sultanate is hinted at in the official statement announcing the raft of fresh agreements — the use of facilities at Duqm will provide the UK with a "strategically important, permanent" maritime base "east of Suez," which will allow the country to "project influence" across the region.

Whitehall and British state appear to be literally dreaming of empire in their return ‘East of Suez’ https://t.co/nOoTprk82c

— Mark Curtis (@markcurtis30) December 12, 2016

The decline of British power in the Middle East and Asia (east of the Suez canal) marked the collapse of its Empire in the wake of World War II — historian Mark Curtis has suggested the UK has demonstrated a clear desire to regain its imperial primacy in recent years, particularly in the aftermath of the 2016 "Brexit" referendum.

"By retaining faith in repressive pro-Western leaders in the region, backing them to the hilt, supplying them with arms and using their territory to militarily intervene in the region, Britain is continuing its long standing Middle East policy. It is as though British leaders simply want to repeat all the counter-productive and immoral episodes of the past, while stirring up even more war and instability in these areas," Curtis has written.