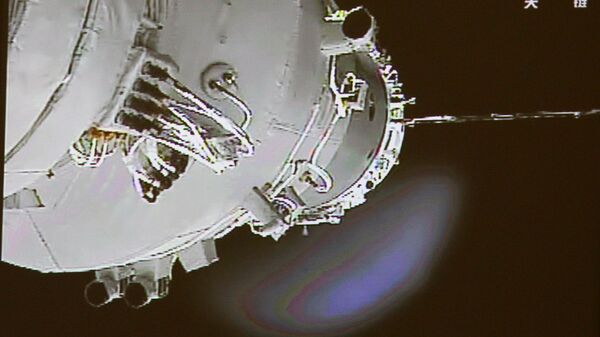

The 8.5-ton Tiagong-1 space station is making a descent toward earth in an uncontrolled fashion. Most of the spacecraft will burn up when reaching the atmosphere, but chunks of it weighing up to 100 kilograms will still hurtle down at earth, astrophysicist Jonathan McDowell told the Guardian Friday.

The Harvard University scientist forecasts Tiagong-1 “will come down a few months from now – late 2017 or early 2018.”

After launching the satellite into space in 2011, Chinese officials ditched the Tiagong-1 space program in 2016 as a result of the object’s mechanical failures. Chinese scientists have estimated that the Tiagong-1 will come back to earth sometime between now and April 2018. Beijing informed the United Nations in May that once the final descent occurs, the multilateral institution will promptly be apprised of the situation.

Injuries are not widely expected however, but McDowell said there’s no way of knowing where the pieces will hit earth. Given that oceans cover 71 percent of the earth’s surface, the odds are Tiagong-1 will hit water instead of land.

Previous failed Soviet and NASA spacecraft plummeted into the atmosphere in 1991 and 1979, respectively, without any injuries. But don’t let this console you: the future does not always resemble the past, as David Hume famously argued in the problem of induction in the late 1700s. And we only have two examples of when this happened, which doesn’t provide much data to make conclusions about what will happen the third time a flying space object approaches earth at high speeds.

It’s worth noting the US space object was 77 tons and the Soviet spacecraft was 20 tons, so there’s much less physical material to actually be hurtled at the species from above, as it were.

Where the failed project is located now provides absolutely no assistance in predicting where the pieces will hit earth. “Even a couple days before it re-enters we probably won’t know better than six or seven hours, plus or minus, when it’s going to come down,” McDowell says, and knowing the time of the re-entry is necessary for calculating where the vessel will come down.

“Not knowing when it’s going to come down translates as not knowing where it’s going to come down,” he says, adding that nearly negligible alterations in atmospheric condition can change the landing location from “one continent to the next.”