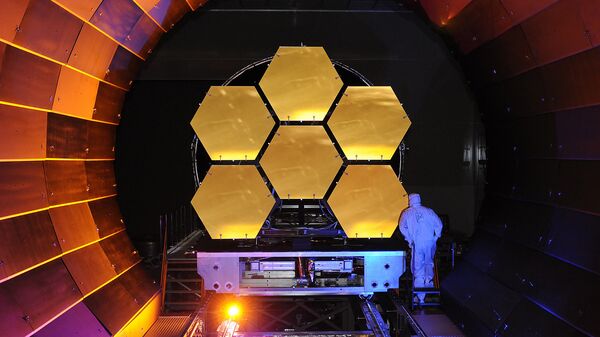

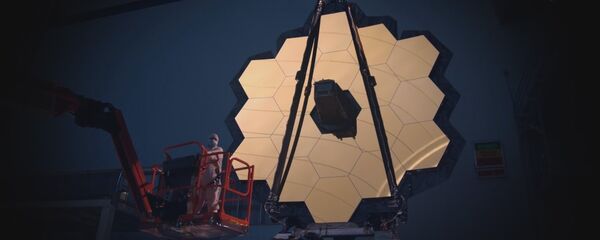

The new NASA telescope, which features an enormous 6.5 meter primary mirror, has successfully passed its 90-day test in a cryochamber, Space.com reports. The telescope underwent tests at near-absolute zero temperatures (40 degrees Kelvin or minus 387 degrees Fahrenheit), all the while in a vacuum.

The incredibly low temperatures were achieved using a double-layered chamber, with the outer shell filled with liquid nitrogen and the inner containing gaseous helium.

"After 15 years of planning, chamber refurbishment, hundreds of hours of risk-reduction testing, the dedication of more than 100 individuals through more than 90 days of testing, and surviving Hurricane Harvey, the OTIS cryogenic test has been an outstanding success," Bill Ochs, project manager for the James Webb Space Telescope, said in the statement.

During tests at the Johnson Space Center in Houston, employees, researchers and scientists survived Hurricane Harvey, which, thankfully did not affect the program.

While in the cryochamber, the telescope was in no way asleep. Instead, the testing team kept checking if the machine was able to operate and adjust its huge multi-faceted mirror, made up of 18 hexagonal, beryllium, gold-coated individual mirrors.

Vacuum testing in low temperatures is a complex task. Without atmospheric pressure, materials can evaporate and condense on the telescope's cold surfaces, damaging its components, Space.com notes.

"This test team spanned nearly every engineering discipline we have on Webb," Lee Feinberg, Webb's optical telescope element manager, said in the NASA statement.

The launch of the James Webb telescope has been delayed several times since the initial 2013 date. The telescope, which already cost $8 billion, was assembled in 2016 and is scheduled for launch in 2019.

"Webb's spacecraft and sunshield are larger and more complex than most spacecraft," said Eric Smith, program director for JWST at NASA headquarters, in a September statement, according to The Space Review.

"The combination of some integration activities taking longer than initially planned, such as the installation of more than 100 sunshield membrane release devices, factoring in lessons learned from earlier testing, like longer time spans for vibration testing, has meant the integration and testing process is just taking longer," he added.