On December 16, 1942, following the success of Operation Uranus, the operation to encircle the German 6th Army at Stalingrad, the Red Army began a massive counter-offensive to try to shift the strategic balance. Soviet high command amassed 36 divisions numbering some 425,000 men, over 5,000 guns and mortars, over 1,000 tanks, and over 400 aircraft of various classes for the assault.

Opposing them were the 8th Italian and 3rd Romanian armies, together with German forces under the command of Field Marshal Erich von Manstein. The 27 Axis divisions in the operational area numbered some 459,000 troops, over 6,000 guns and mortars, about 600 tanks, and 500 aircraft. Axis forces enjoyed the additional benefit of being heavily entrenched behind two defensive lines running 25 km in depth.

Notwithstanding the enemy's numerical superiority and defense in depth, the Red Army managed, in two weeks, to break through the front to a width of 340 km, destroying 11 enemy divisions and ending up to the rear of Manstein's Army Group Don. The operation proved successful in large measure due to the effective use of Soviet air power. By December 30, 1942, Soviet troops captured 60,000 Axis troops, nearly 2,000 guns, 176 tanks, and 370 enemy aircraft. As a result of the operation, the German goal of relieving the forces trapped in the Stalingrad pocket became a lost cause.

Fight for the Kuban

By the spring of 1943, replenished from the disastrous losses of 1941 and heartened by the victory at Stalingrad, the Red Air Force stepped up efforts to challenge Axis air superiority on the Eastern Front. This included a series of major air battles over the southern Kuban River. The air campaign, lasting between April and June 1943, became a turning point in the battle for the Caucasus. The Luftwaffe, looking to use its numerical superiority and traditional tactical edge to its advantage, planned to swiftly destroy local Red Air Force assets before turning its attention to ground support missions.

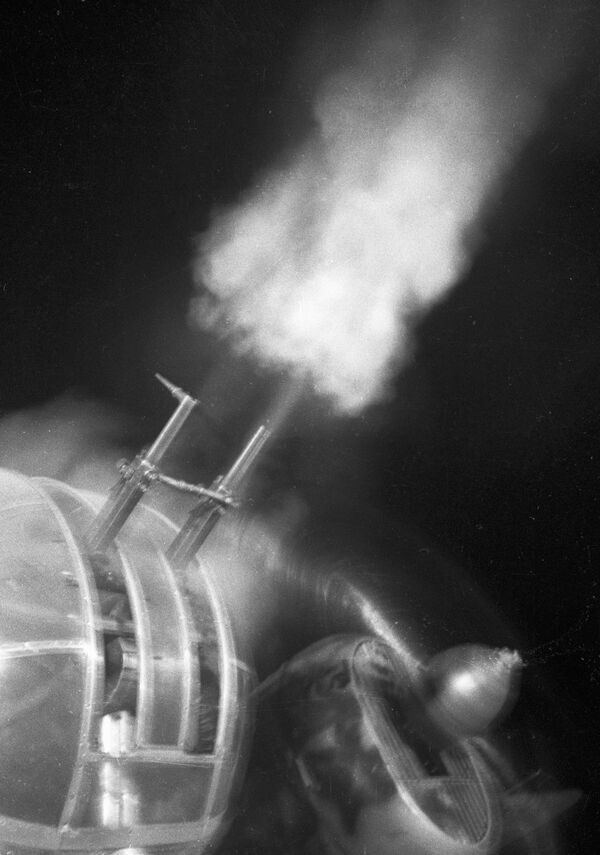

Axis forces, consisting of about 1,200 aircraft, including the Luftwaffe's mainstay BF-109 and FW-190 fighters and He-111, Ju-87 bombers and Ju-88 multirole combat aircraft, matched up against an assorted collection of Soviet and lend-lease Red Air Force planes, including LaGG-3, La-5, Yak-1B, Yak-7, P-39 Airacobra, P-40E Kittyhawk and British Spitfire MK.V fighters, and Pe-2, Il-2, and Il-4 bombers and ground attack aircraft.

The second stage of the campaign started on April 28 over Krymskaya village. In the first three hours, German aviation carried out over 1,500 sorties, in an attempt to disrupt the ongoing Soviet ground offensive. Soviet air power responded the following day, conducting 379 sorties against Axis troops. Intense air battles, running until May, resulted in the loss of dozens of aircraft on both sides, as Soviet forces continued their advance to a depth of 10 km around the village by the middle of the month. Effective Soviet use of fighter aviation forced Luftwaffe bombers to climb to 3,000-5,000 meters for their missions, significantly reducing their accuracy and overall effectiveness.

The last stage, beginning on May 26 and running through June 7, involved heavy fighting in the vicinity of villages of Kievskaya and Moldavskaya, where continued Axis air superiority threatened to stop the Soviet advance in its tracks. Nonetheless, the Luftwaffe's failure to stop the Red Army's offensive in the face of heavy resistance by Soviet air units helped put a dent its regional air superiority, and led to the loss of air supremacy theater-wide by the summer of 1943.

British intelligence later concluded that the growing intensity of Soviet pressure against Luftwaffe operations in 1943 helped lead to the Luftwaffe's exhaustion, making it impossible for the German air force to conduct major operations elsewhere. Ultimately, in the three month Kuban operation, the Red Air Force lost an estimated 750 aircraft, while destroying some 1,100 enemy planes.

Among the most devastating consequences of the surprise Nazi German invasion of June 1941 was the Luftwaffe's success in swiftly destroying several thousand Soviet aircraft on the ground. On May 6-8, 1943, the Red Air Force decided to return the favor, launching an assault that would help it gain and hold air superiority in the central and southern sectors of the Eastern Front.

With Soviet intelligence already aware of the planned German tank offensive against the Kursk salient, an operation to cut down at least some portion of Axis air support became vital for Soviet high command.

On the morning of May 6, 434 Soviet aircraft simultaneously struck 17 enemy airfields, destroying nearly 200 planes on the ground and another 21 in air battles over enemy-held territory. Soviet planes returned at 3 pm the same day, hitting 20 enemy airfields with 372 aircraft. The next morning, a third strike was carried out, with 22 airfields targeted. Subsequently, the Luftwaffe was forced to relocate most of its remaining aircraft to rear and reserve airfields and to carefully camouflage them.

The airfield attacks helped to temporarily reduce the strength of Nazi air power ahead of the battle at Kursk, where over 2,150 Soviet fighters and bombers faced off against 2,050 Luftwaffe planes. In the course of that gruesome campaign, from July 5-August 23, the Red Air Force lost over 1,600 planes, but destroyed some 1,696 Luftwaffe planes in the process.

Eastern Front Air Combat in the Big Picture of WWII

In much of Western and Russian historiography, the Soviet-German air war on the Eastern Front has often been overshadowed by the titanic struggle on the ground, and by the Luftwaffe's air battles against the Western allies on the Western Front. The lack of complete, verifiable archival data for Luftwaffe losses starting in mid-1944 and especially in 1945 has led to considerable debate among scholars about Axis losses, including losses by theater.

According to estimates compiled by Russian historian Oleg Smyslov, the Luftwaffe lost a total of 52,850 aircraft on the Eastern Front in WWII, accounting for 61% of Germany's total losses of 85,650 planes across both fronts. Soviet losses in the same period amounted to an estimated 106,400 planes, 46,100 of those lost in combat and 60,300 lost in non-combat circumstances. Furthermore, while the Red Air Force lost an estimated 48,000 air force personnel, including 28,193 pilots, during the war, estimates of German losses vary from 27,000-66,000 combat deaths on both fronts.

German, American and other Western historians have presented statistics on kills and losses which conflict sharply with Soviet and Russian estimates. But while debates regarding the figures are almost certain to continue, the big picture has long been clear: that the ferocity of Soviet-Axis air battles on the Eastern Front matches the immensity of the Great Patriotic War as a whole, helping to make it the greatest and most horrific military confrontation in human history.