In 2016, the China National Space Administration (CNSA) reported that they had lost control of Tiangong-1 and were unable to perform a controlled re-entry, meaning it would eventually be pulled back towards Earth and crash into the planet. Fortunately, Earth's atmosphere will disintegrate most of the 9.4-ton satellite.

But most is not necessarily all. The Washington-funded Aerospace Corporation, whose mission is to advise governments and private enterprises on spaceflight, claimed that there was "a chance that a small amount of debris" will survive re-entry.

"If this should happen, any surviving debris would fall within a region that is a few hundred kilometres in size," Aerospace added in a Tuesday statement. They unhelpfully provided a map of places where the debris might rain down that includes northern China, the Middle East, southern Europe, the northern US, New Zealand, Tasmania, and parts of Chile and Argentina.

They weren't able to accurately date its descent, either. Aerospace reported sometime between March 24 and April 15, while the European Space Agency claimed between March 24 and April 19.

"You really can't steer these things," Harvard astrophysicist Jonathan McDowell told The Guardian when the descent was first announced in 2016. "Even a couple of days before it re-enters we probably won't know better than six or seven hours, plus or minus, when it's going to come down. Not knowing when it's going to come down translates as not knowing where it's going to come down."

"There will be lumps of about 100 kg [221 pounds] or so, still enough to give you a nasty wallop if it hit you," he said. "Yes there's a chance it will do damage, it might take out someone's car, there will be a rain of a few pieces of metal, it might go through someone's roof, like if a flap fell off a plane, but it is not widespread damage."

Oh, and the Tiangong-1 was reportedly carrying hydrazine, a rocket fuel component that is toxic to humans. According to the US Environmental Protection Agency, hydrazine can cause "irritation of the eyes, nose, and throat, dizziness, headache, nausea, pulmonary edema, seizures, coma in humans. Acute exposure can also damage the liver, kidneys, and central nervous system. The liquid is corrosive and may produce dermatitis from skin contact in humans and animals."

So that's potentially toxic and corrosive space debris raining down on your head. Thanks, China.

Aerospace stressed that even in the affected areas, the chances of Tiangong-1 debris hitting someone were astronomically (no pun intended) low.

"When considering the worst-case location… the probability that a specific person (ie, you) will be struck by Tiangong-1 debris is about 1 million times smaller than the odds of winning the Powerball jackpot," they wrote.

"In the history of spaceflight no known person has ever been harmed by reentering space debris. Only one person has ever been recorded as being hit by a piece of space debris and, fortunately, she was not injured."

So if you get hit by a piece of sky metal in the next few weeks, take cold comfort in the fact that you won the toxic Chinese space junk lottery.

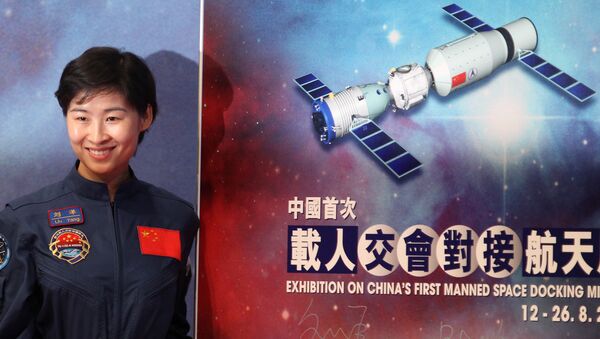

Tiangong-1, whose name means "Heavenly Palace," was launched in 2011 as part of Beijing's push to become a major player in aerospace. The industry leaders, the US and Russia, have a multi-decade head start, but China has attempted to compensate by quickly developing their own large-scale program. The main purpose of Tiangong-1 was to test orbital rendezvous and docking capabilities.

Satellite debris has rained down on Earth a few times before. Unlike Tiangong-1, debris from NASA's Skylab was judged to be relatively likely to hit someone when it made its re-entry in 1979. Several pieces of the 170,000 pound space station fell on Western Australia, but didn't hit anybody.