Russia first began production of chemical weapons in 1915 during World War I, as a symmetrical response to Germany, which casually used the poison gas weapons on the battlefield on both the Western and Eastern fronts. The Czarist government speedily built three plants – in Ivanovo-Voznesensk, Moscow and Kazan. In a year's time, the Imperial Russian Army amassed nearly 150,000 chemical shells, but would refrain from using them out of fears regarding their unpredictability depending on weather conditions.

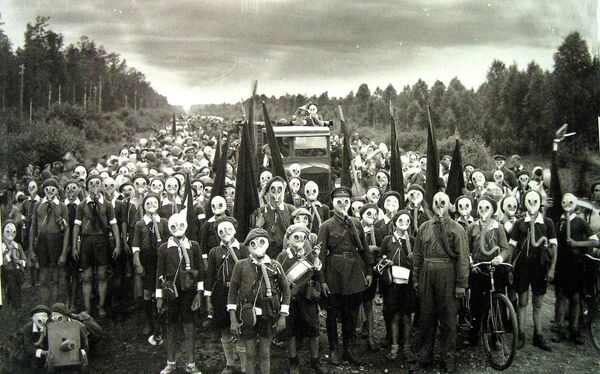

After the Bolsheviks came to power, they quickly established the so-called Chemical Service of the Red Army. The military created chemical units in all rifle and cavalry divisions and brigades, and modern chemical training was established in 1925.

During the Second World War, amid fears that Nazi Germany might repeat its WWI practice of using chemical weapons, the Red Army maintained forces and means to defend against and respond to such an attack, creating 19 chemical weapons brigades by 1944. Thankfully, the weapons were never used on the battlefield, and most of these units were disbanded after the war ended.

With the onset of the Cold War between the Soviet Union and the United States in the late 1940s, both sides began building up massive stockpiles of chemical warfare agents and the means to defend against them.

"By 1990," Kotz recalled, "the Soviet Union had nearly 40,000 tons of chemical weapons, including over four million artillery and missile munitions. 80% of this huge arsenal consisted of sarin, soman, VX, and other nerve gases. The rest were stocks of lewisite and Mustard-Lewisite Mixture (HL) blister agents."

After the Soviet collapse, Russia signed the Chemical Weapons Convention, ratifying it in 1997. The arms treaty, which prohibits the production, stockpiling and use of chemical weapons and their precursors, committed Moscow to the destruction of the deadly weapons. President Boris Yeltsin signed the federal law approving the weapons' destruction in May 1996.

Russia stored its chemical weapons stocks at seven well-guarded arsenals in the Udmurtia, Kurgan, Bryansk, Saratov, Penza and Kirov regions. The majority of its stocks destroyed directly in their warehouses; additional facilities were created at four of these locations to help with the disposal.

It took nearly twenty years, but in September 2017, Russian President Vladimir Putin presided by videoconference over the destruction of Russia's last chemical artillery round at the Kizner plant in Udmurtia.

Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons deputy director-general Hamid Ali Rao oversaw the last round's destruction, calling it a "momentous occasion" and voicing his appreciation for Putin's "personal interest and decisions" in the destruction of the Russian stockpile. OPCW director Ahmet Uzumcu signed a document confirming Russia's destruction of all of its chemical weapons.

But Russia wasn't the only country in the former USSR that was left with chemical weapons production facilities after the Soviet breakup. Arms were also manufactured and stored at facilities in Belarus, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Moldova, Ukraine and Uzbekistan.

In 1999, chemical weapons specialists from the US military travelled to the Nukus Chemical Research Institute in Uzbekistan to help dismantle the plant. Speaking to Kotz, former UN Chemical and Biological Weapons Commission member Igor Nikulin recalled that the Uzbek stocks were destroyed by the US Army Corps of Engineers. He added that he believed it was likely that the US experts "took some of these with them back with them" to the United States.

In June 2004, for example, residents in the village of Toporivka in Chernivtsi, western Ukraine dug up a box of 76 mm shells. Explosives experts called to the scene quickly determined that these were chemical rounds. The shells were taken to a specialized disposal area for destruction. But questions about who hid them there, and whether there were other similar troves elsewhere were never answered.

Thankfully, Kotz noted, "it's unlikely that such weapons can be used for their intended purpose. Without special storage conditions, chemical weapons quickly deteriorate."