The project is headed by the Sanya Institute of Remote Sensing in Hainan and has been sponsored by the provincial government, according to the China News Service. In total, 10 satellites will be launched into low-Earth orbit by the end of 2021.

According to the institute, the first three Hainan-1 optical satellites will be sent off into orbit sometime during the second half of 2019 and will be followed by three more Hainan-1 satellites and two Sanya-1 multispectral remote-sensing satellites in 2020. The final two, both Sansha-1 synthetic aperture radar satellites, will go up in 2021.

A state report issued on the project noted that Hainan-1 satellites would "monitor every reef and ship within the South China Sea" to offer "accurate and quick response" in emergency situations.

"The combination of cameras and automatic identification systems will allow us not only to monitor ships lawfully sailing in the South China Sea, but also to detect and track illegally operating ones," Yang Tianliang, director of the Sanya Institute, told the China News Service on Wednesday.

Cameras on the Hainan-1 satellites will be able to monitor large and mid-sized ships, while the Sanya-1s will assess water conditions, the South China Morning Post reported. The Sansha-1 satellites will offer all-weather, high definition monitoring.

Although the program is expected to offer aid in weather tracking and emergency situations, Chen Xiangmiao, a researcher with the National Institute for the South China Sea, told the China News Service that the project will also play a role in national defense. Per Chen, the technology will aid Beijing in negotiating the demarcation of the disputed waters.

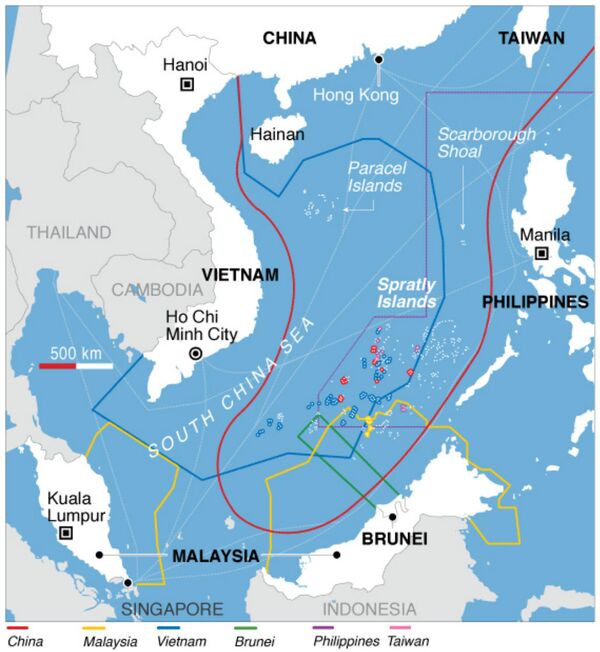

The resource-rich waters have been involved in a longstanding dispute, as countries including China, the Philippines, Brunei, Vietnam, Malaysia and Taiwan have picked apart the sea and claimed territories for themselves.

Rupert Hammond-Chambers, president of the US-Taiwan Business Council, told Sputnik Thursday that the new satellites "will provide the PRC [China] with a greater degree of actionable intelligence which is likely to be employed in undermining counter claims and efforts by other countries to establish their sovereignty."

He also noted that, "It may have a practical effect if the intelligence is used to track non-PRC fishing boats and the information is used to interdict them while they are working. This could be a real flashpoint. Consider the cod wars between the UK and Iceland in the 1970s as an example of how natural resources can become a flashpoint for broad tension."

China's move to construct artificial islands and stock them with military equipment has been a thorn in critics' sides, as many argue that the move is simply intended to expand China's stake in the sea, with implied threats of violence if it's challenged.

"I don't believe the deployment of new capabilities by the PRC will deter other claimants from pressing their interests," Hammond-Chambers told Sputnik. "I do think it unlikely that international courts will be pursued given the non-use of the recent ruling by the Hague declaring the PRC's claims to be spurious. I'd expect PRC military aggression and coercion to be met more head on by claimants as well as interested parties such as the US, Australia, India and the Europeans."

In 2016, a Hague-based arbitration tribunal ruled that China had no legal basis for claiming historic rights over areas falling within the so-called "nine-dash line" — a vague demarcation line Beijing uses to claim parts of the South China Sea.

Beijing refuses to recognize the verdict and says the matter be resolved through negotiations with other claimants.