What's the Big Deal?

The INF deal was big, in fact, but we can realize its importance only if we take a look at the international situation in the mid-1970s. By that time, the two superpowers had roughly achieved strategic parity after three decades of the overwhelming dominance of the US in nuclear force.

While the Cold War between the United States and the Soviet Union was going through a period of détente, Washington began to modify its forward-based system in Europe with submarine-launched and intermediate-range ballistic missiles. This was seen as a cause for concern in Moscow, which responded by upgrading the aging missiles on its Western flank with state-of-the-art weapons, classified by NATO as SS-20 "Pioneer." These strategic nukes allowed the Soviet Union to place all major facilities in Western Europe in its crosshairs, thus obtaining a perceived military advantage in Europe.

After Moscow's move had made waves in the West, particularly in Germany, NATO adopted a "double-track" decision to deploy Pershing II and Tomahawk missiles in its Western European member countries while at the same time talk the USSR into limiting its European nuclear weapons.

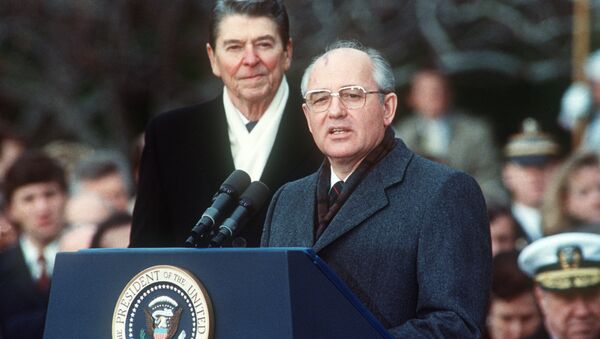

Years of negotiations have come to a political deadlock until Mikhail Gorbachev, a vocal proponent of global nuclear disarmament, concluded the INF Treaty with Ronald Reagan in 1987. According to the deal, the United States and the USSR pledged to terminate their nuclear and conventional missiles and their launchers with ranges of 500-1,000 km and 1,000-5,500 km. The ban between Moscow and Washington resulted in 2,692 missiles being destroyed by the treaty's deadline of June 1, 1991.

In addition, then-Secretary of State James Baker promised that NATO would not expand "one inch eastwards" towards the Soviet Union's borders.

At the time, the signing of the pact was widely seen in the Soviet Union as an act of good will (if not a concession) from Gorbachev as he additionally vowed to eliminate the Oka ballistic missiles (NATO designation SS-23 Spider), whose range was just below 500km and which therefore were not compatible with the original pact.

More importantly, however, the INF Treaty became an unprecedented step in trimming nuclear arsenals and defusing Cold War tensions, as well as the first agreement to stipulate an actual reduction in nuclear arms rather than simply curbing their proliferation.

Washington's Excuse

But this week, Donald Trump's latest itch for killing off international agreements led to him announcing the US withdrawal from the landmark treaty. The POTUS gave several explanations at a time and first off, he accused Russia of breaching the pact "for many years." His allegations come on the heels of previous claims from US hawks that Russia's new 9M729 ground-based cruise missile system violates the INF Treaty because it gives Russia the possibility of launching a nuclear strike in Europe with little or no notice.

What Donald Trump also hinted at is that the deal doesn't affect China in any way, tying the hands of his officials in response to Beijing's military buildup in the Western Pacific. As China has yet to place its signature on the agreement, it isn't obliged to limit neither the development nor proliferation of intermediate-range nuclear missiles.

"Unless Russia comes to us and China comes to us and they all come to us and they say, ‘Let's all of us get smart and let's none of us develop those weapons,' but if Russia's doing it and if China's doing it and we're adhering to the agreement, that's unacceptable," Donald Trump said at a campaign rally in Nevada, boasting that he had a lot of cash "to play with our military."

Moscow Hits Back

Russia commented on Trump's intention to scrap the pact by citing Washington's dreams of a unipolar world. Deputy Foreign Minister Sergei Ryabkov accused Trump of "blackmailing" and said that there is no substance to the US's claims that Russia is violating the INF treaty.

Russian lawmaker Alexey Pushkov views the US's looming pullout of the deal as yet another blow to the global system of security, coming on the heels of its 2001 exit from the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty.

Moscow notes that the Russian missiles that allegedly violate the pact correspond to its obligations under the treaty and have not been upgraded and tested for the prohibited ranges. Russia went on to voice its own doubts over Washington's compliance with the treaty, particularly over the ground-based deployment of Aegis Ashore systems in Romania and Poland, which can be used to launch medium-range Tomahawk missiles.

Moreover, Russia stresses, US unmanned aerial vehicles or armed drones also fall under the INF Treaty definition of ground-launched cruise missiles as their flight ranges (1,100 km) and lack of pilot mean that drones of this type are similar to shorter-range cruise missiles.

In June, the defense ministry said in a statement that the United States was seeking a pretext to leave the treaty in a bid to gain the upper-hand in European security. This could be achieved by deploying missiles in Central and Eastern Europe with shorter flight time to Russian targets — something that would be a great advantage in the event of a potential nuclear conflict with Moscow.