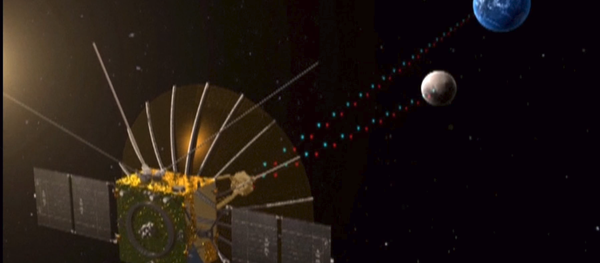

The US Air Force's "Project Thor" revives a dream weapons manufacturers have had since the dawn of nuclear weapons: how to create damage equivalent to a nuclear bomb without the trouble of nuclear radiation and fallout. Kinetic bombardment, once prohibitively expensive, is now back on the agenda, since it involves no explosives and is not technically barred from being put into orbit by the Outer Space Treaty.

The proposal involves placing into orbit a bundle of telephone pole-sized rods made out of tungsten, an extremely durable metal with the highest melting point of any element. The rods could be dropped from orbit at the right moment, accelerating during their thousand-mile plummet to Earth to more than 10 times the speed of sound.

It's easy to see why the New York Times called them "tungsten thunderbolts." A more common nickname for the weapon is simply "rods from God." The power of the impact would be similar to the explosive yield of a ground-penetrating nuclear weapon, We Are the Mighty reported Monday. Unlike nukes, the rods from God generate zero fallout.

‘Project Thor’ came to be during #Vietnam..hundreds of small projectiles from a few thousand feet, ‘Thor’ used large projectiles "rods from god" were bundled (20 feet long, 1 foot in diameter) tungsten rods, dropped from orbit, reaching a speed of up to 10X the speed of sound pic.twitter.com/ZRNmQvi7kb

— geo (@delgeo1) November 7, 2018

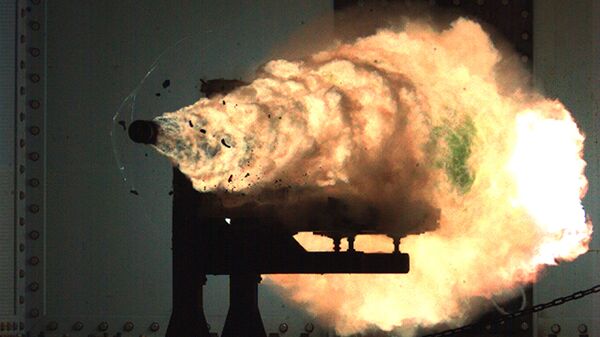

The idea is not fundamentally different from that behind a rail gun: the projectile uses no explosive, relying only on its tremendous speed — remember net force is just mass times acceleration — to annihilate whatever object it strikes. While a rail gun accelerates its projectile using electromagnetic energy, Project Thor relies on the potential energy of Earth's gravity: it just lets go, and down they fall.

WAtM estimated the cost of lifting objects into space at $10,000 per pound, meaning that 200 cubic feet of tungsten rod, which weighs around 24,000 pounds, would cost about $230 million per rod to place into orbit. Compared to Breaking Defense's estimated cost of $212.5 million apiece for the Air Force's proposed next generation of intercontinental ballistic missiles, the Ground-Based Strategic Deterrent, the difference seems almost negligible, especially when the danger of radioactive fallout is removed from the equation.

The US Air Force deployed a similar weapon during the Vietnam War. So-called "Lazy Dog" bombs were 2-inch long cylinders of solid steel, fitted with fins and dropped from several thousand feet up. They could reach 500 miles per hour during their fall and penetrate 9 inches of concrete, WAtM noted. However, the proposed orbital "rods from God" would drive hundreds of feet underground, penetrating even the deepest and most fortified bunker or missile silo.

The Pentagon revived the idea in the early 2000s, weighing the option of using them to strike underground nuclear sites in rogue nations. In 2002, a RAND report titled "Space Weapons, Earth Wars," dedicates no small amount of space to the concept and the Air Force's 2003 "Transformation Flight Plan," references "hypervelocity rod bundles" in its outline of future space-based weapons, the San Francisco Chronicle notes.

The Pentagon continued to research kinetic energy weapons, such as the railgun the Office of Naval Research claimed in 2012 can throw a 25-pound "hypervelocity projectile" with 32 megajoules of energy, penetrating seven steel plates and destroying whatever sits on the other side. "One megajoule of energy," the office notes, "is equivalent to a 1-ton car traveling at 100 miles per hour."

"The classic way of delivering hurt against a target has been to pack a lot of chemical explosive into a container of some kind, a barrel or a cannonball or steel bomb," Matt Weingart, a weapons program development manager at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, told Task & Purpose in June 2017.

"The violence comes from the chemical explosive inside that bomb sending off a blast wave, followed by the fragments of the bomb case. But the difference with kinetic energy projectiles is that the warhead arrives at the target moving very, very fast — the energy is there to propel those fragments without the use of a chemical explosive to accelerate them. The more mass, the more violence," Weingart said.

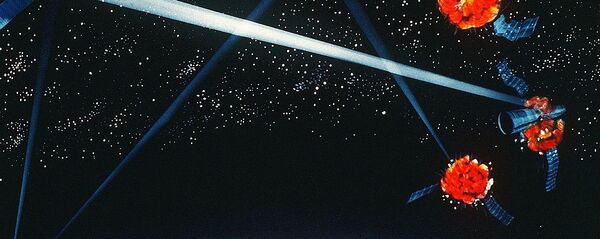

But the US is expanding its nuclear arsenal, or at least US President Donald Trump wants to. So why is Washington once again exploring "tungsten thunderbolts?" The growing militarization of space may hold the answer. As weapons without explosives, chemicals or nuclear material, the "rods from God" aren't technically banned from space under the 1967 Outer Space Treaty or any other associated treaties, which are legally non-binding.

While other countries, including Russia and China, have been pressuring the US to sign "an international, legally binding instrument on the prevention of an arms race in outer space," as a draft resolution put before the UN in October 2017 called it, Washington has been adamant in its rejection of such treaties. That disregard for international disarmament showed up once again in Trump's threats to scrap the Intermediate Range Nuclear Forces Treaty (INF), a 1987 document limiting nuclear weapons with very short warning times.

In 2014, the US rejected the draft Treaty on Prevention of the Placement of Weapons in Outer Space and of the Threat or Use of Force Against Outer Space Objects (PPWT) on the grounds that it was "fundamentally flawed" for not covering ground-based weapons, Space News reported at the time.

More recently, German Foreign Minister Heiko Maas and Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov have made overtures to renew talks on the INF treaty as well as a new Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (START), which aims at general arms reduction, and to begin to take seriously the threat of space-based weapons.

"We are very concerned about the danger of the transformation of outer space into a sphere of armed confrontation. This subject has become more and more worrisome recently," Lavrov said at a news conference on November 2.

"Space weapons and autonomous weapons will soon no longer be science fiction, but possible reality," Maas said in an interview on Wednesday. "We need rules that keep pace with the technological development of new weapons systems."