The magnetic pole is a slow but steady wanderer, and geologists say it is moving from the Canadian Arctic towards Russia's Siberia at an annual rate of more than 55 kilometres.

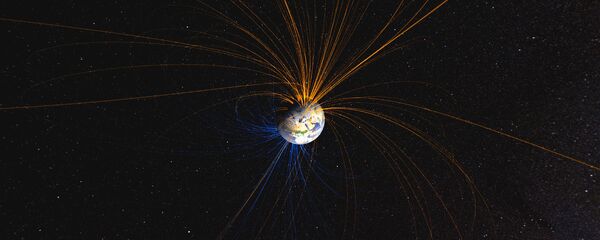

This shift is caused by convection — a slow rotation of fluid rock and molten metal in the earth's outer core — and it is the liquid metal that generates our planet's huge magnetic field.

"It's the change in speed of the rotation of the different parts of the outer core, that means the movement of the magnetic north pole is not the same speed through time," Dr. Paul Byrne, an assistant professor at the North Carolina State University, told the CBS 17 TV station.

Knowing the location of the magnetic north pole is crucial to navigation systems containing magnetic compasses.

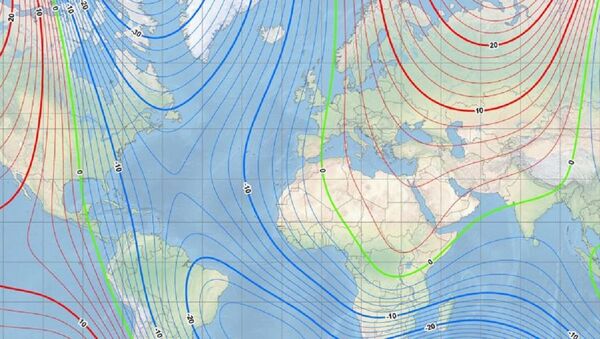

For this reason, scientists have developed the World Magnetic Model, a representation of the earth's magnetic field, which allows magnetic north to be precisely fixed.

An updated version of the model is released every five years. The next release was scheduled for late 2019, but recent shifts have prompted scientists to roll out the update earlier this month.

They reassure that the changes will be relatively minor for the average user and will mostly affect those living or trekking around the high Arctic. The update is also expected to come in handy to militaries, commercial airlines, search-and-rescue ships and aircraft, NASA, and other agencies and groups relying on precision navigation in the high north.

According to Dr. Byrne, "these maps are used for all kinds of things including navigation of aircraft, of military vehicles, for understanding where people are on Earth. Honestly, this doesn't make a huge difference to people who are not living very close to the pole. It really only effects folks who are really close to the magnetic north pole."

He adds that navigation apps "are going to take on more of this updated magnetic field map and as a result of that, users won't see any difference themselves using their phones, they're good."