Normally, the transfer of energy from a warmer place to a cooler place happens through radiation — that is, it spreads out in every direction at once until it reaches a temperature equilibrium. However, a couple of MIT scientists have used lasers to make heat move like sound waves: creating spots where it was extra-warm and spots where it was much cooler. They published their results in Science on March 14.

"Normally, the heat would gradually diffuse from the heated regions to the unheated regions, until the temperature pattern was washed away," study researcher Keith Nelson, an MIT chemist, told Live Science for a March 14 article. "Instead, the heat flowed from heated to unheated regions, and kept flowing even after the temperature was equalized everywhere, so the unheated regions were actually warmer than the originally heated regions."

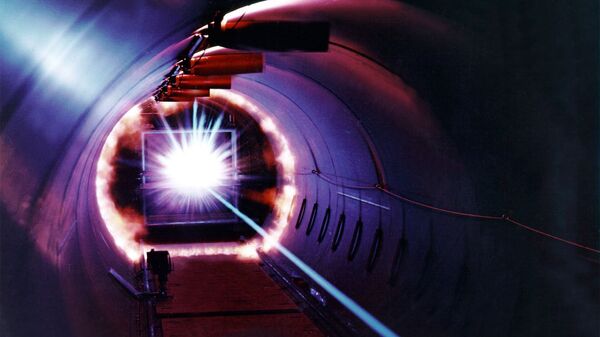

The scientists zapped graphite that had been chilled to —240 degrees Fahrenheit with two lasers that crossed each other to form an interference pattern — that's when the light waves interact so that in some places they amplify each other and in other places cancel each other out.

They suspected this would force heat to move in a specific way because of how it transfers through solids, which don't have atoms capable of moving around like in the air. In solids, heat transfers via sound waves, which move from atom to atom.

However, no matter which material it happens in, heat transfer is slow — just think about how long a boiled kettle takes to return to room temperature, or how long it takes your kitchen to return to the temperature of the rest of the house after having baked in it. That's what made the results of this experiment extra-special: the heat transferred really quickly, at the speed of sound.

"Heat flowed much faster because it was moving in a wave-like fashion without scattering," Nelson told Live Science. They called this phenomenon "second sound."

"From a fundamental perspective, this is just not ordinary behavior. Second sound has only been measured in a handful of materials ever, at any temperature. Anything we observe that's far out of the ordinary challenges us to understand and explain it," Nelson said.

"If it makes it to room temperature in some materials, then there would be prospects for some applications," he said, such as rapidly cooling down electronic devices.