Avi Loeb, the chair of astronomy at Harvard University along with the study’s lead author Amir Siraj, an undergraduate student at Harvard University, suggested they may have detected an interstellar meteor, the solar system's second known interstellar visitor, which could potentially help life travel from star to star.

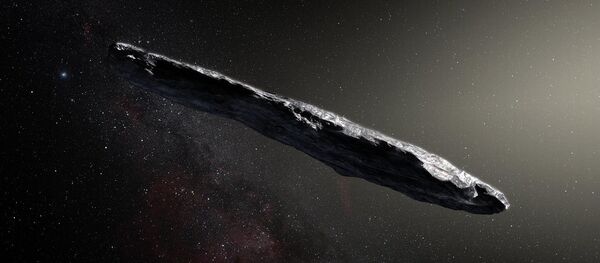

The first known visitor from interstellar space, a cigar-shaped object named "Oumuamua", was detected in 2017. Scientists deduced the origins of the 1,300-foot-long (400 meters) object from its speed and trajectory, which suggests it may have come from another star, or perhaps two, however, Loeb suggested that smaller interstellar objects could have collided with the Earth before.

The scientists analysed the Center for Near-Earth Object Studies' catalogue of meteor events detected by US government sensors, focusing on the fastest meteors, as a high speed suggests a meteor is potentially not gravitationally bound to the sun and thus may originate from outside the solar system.

READ MORE: Scientists Reveal ‘Simplest Explanation’ About Mysterious Oumuamua

They identified a meteor about 0.9 meters wide that was detected on Jan. 8, 2014, at an altitude of 18.7 kilometres over a point near Papua New Guinea's Manus Island in the South Pacific. Its high speed of about 216,000 km/h and its trajectory suggested it came from outside the solar system, the scientists said.

"We can use the atmosphere of the Earth as the detector for these meteors, which are too small to otherwise see," Loeb told Space.com.

The meteor's velocity suggested it received a gravitational boost during its journey, perhaps from the deep interior of a planetary system, or a star in the thick disk of the Milky Way.

"You can imagine that if these meteors were ejected from the habitable zone of a star, they could help transfer life from one planetary system to another," Loeb said.

Assuming Earth sees three meteors with potential interstellar origins every 30 years or so, the researchers estimated there are about a million such objects per cubic astronomical unit in our galaxy. (One astronomical unit, or AU, is the average distance between Earth and the sun – about 150 million km.) This suggests each nearby star might gravitationally sling about 60 billion trillion such rocks from its system, equal to about 0.2 to 20 times the mass of Earth. Ten billion trillion is "roughly the number of stars in the observable universe," Loeb said.

Siraj and Loeb noted that analysing the gaseous debris of interstellar meteors as they burn up in Earth's atmosphere could shed light on the composition of interstellar objects. They also want to set up an alert system that automatically trains telescopes on meteors travelling at high speeds to analyse their gaseous debris, Loeb said. "From that, we could infer the compositions of interstellar meteors," he added.