Sale of the three dozen attack helicopters and associated weaponry, parts and other equipment was allowed to move forward on Tuesday, according to a bulletin by the Defense Security Cooperation Agency (DSCA), a Pentagon bureau that handles foreign military sales.

“This proposed sale will support the foreign policy and national security of the United States by helping to improve the security of a major Non-NATO ally that is an important force for political stability and economic progress in North Africa,” the DSCA noted. “The proposed sale will improve Morocco's capability to meet current and future threats, and will enhance interoperability with US forces and other allied forces. Morocco will use the enhanced capability to strengthen its homeland defense and provide close air support to its forces.”

The move follows a September decision to sell Rabat more than $1 billion in munitions, including smart bomb kits and TOW missiles, and an even bigger sale approved in March of 25 F-16V Viper fighter jets for $3.78 billion. Defense News noted following the September sale that Morocco had requested an incredible $7.26 billion worth of weapons from Washington, “easily the most of any nation.”

Through its Foreign Military Financing (FMF) program, the Pentagon furnishes friendly governments with money to buy military hardware from the US; in 2018, Morocco received $10 million via the FMF, according to a Congressional Research Service report from October 2018.

Taiwan also bought the advanced Viper jets earlier this year, and Indonesia has expressed interest as well.

Western Sahara, Yemen Conflicts

However, the Royal Moroccan Armed Forces haven’t fought a real war since 1963, when a short-lived border conflict broke out with the newly formed independent Algerian state over land claims in the Sahara. So what do they need these weapons for?

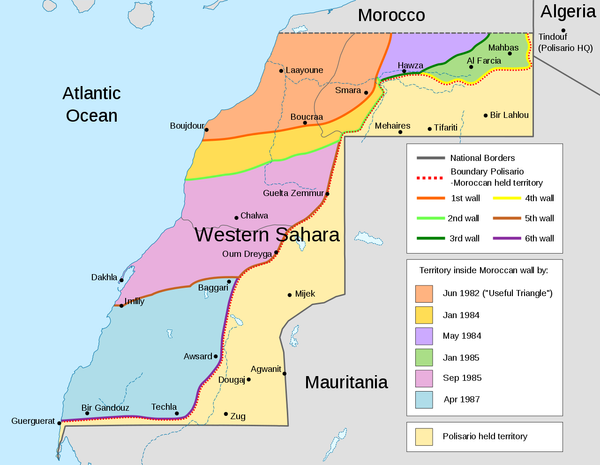

Lasting anxiety over Morocco’s Sahara land grab led to Algerian support for an emerging nationalist movement in Spain’s Spanish Sahara colony by the Sahrawi people. Morocco also claimed the territory, and when Spain withdrew in 1975, Rabat invaded, locking it in a war with the Sahrawi Polisario Front, which declared an independent Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic in Western Sahara.

To ensure control over the territory and its phosphate deposits, Rabat constructed a 1,700 mile-long sand berm isolating the desirable parts of Western Sahara from the rest of the country. Most of the 175,000-strong Moroccan military spends its time occupying this massive fortification. Polisario continues to operate in the so-called “free zone” east of the sand berm, awaiting a promised referendum on independence for Western Sahara that has never materialized.

Morocco was ejected from the African Union due to the war, and some countries, such as South Africa, only re-established diplomatic ties with Rabat in recent years, after Morocco was readmitted. Others, such as Algeria, have continued their support for Polisario, leading to accusations last year that Iran and Hezbollah were supporting the group via Tehran’s Algiers embassy.

In the row, which saw Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates support Morocco’s claim that Hezbollah was training with Polisario in the Western Sahara, Rabat cut ties with Tehran despite denials by Iran, Polisario, Algeria and Hezbollah that such transactions occurred.

The UAE and Saudi Arabia have consistently supported Morocco’s claims over Western Sahara, and in turn, Moroccan pilots have participated in the Riyadh-led coalition’s devastating war in Yemen, only withdrawing from the war in February 2019, Al Jazeera reported.