Supermassive black holes known by science to be at the core of galaxies may be generating hot, turbulent waves of gas throughout the cosmos, and thus preventing galaxy clusters from dying in just a few billion years, claims a study published to the arXiv database on 18 November and yet to be peer reviewed.

For the first time, a team of astrophysicists believe they've caught a glimpse of that turbulence in action.

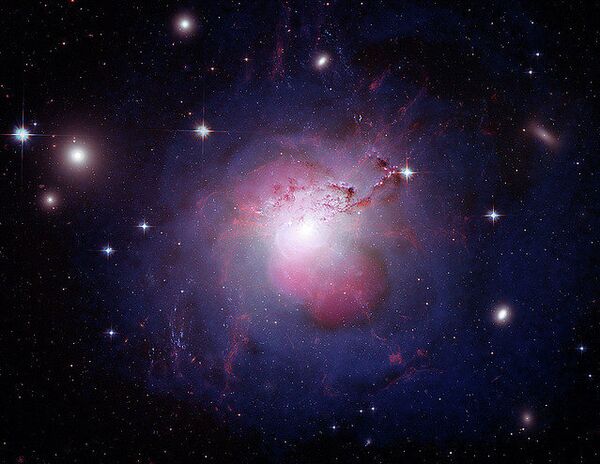

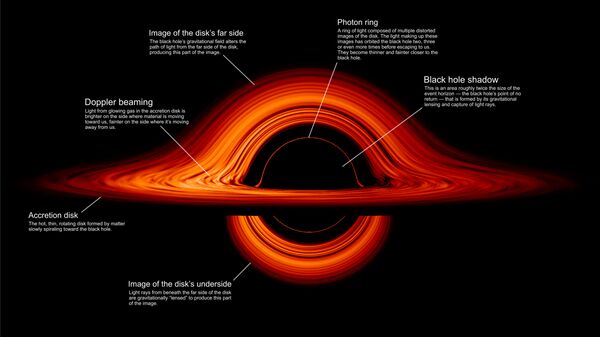

Hot gas swirls at the core of huge galaxy clusters. Science has been seeking an explanation for how it retains its heat.

Simple models suggest the gas should lose energy, with gravity starting to bind the cloud together into stars within about a billion years of it forming.

In turn, the stars would burn out, and the galaxy would die in what is referred to as a "catastrophic cooling". However, this does not occur.

Back in 2005, a team of researchers found a partial explanation for this, as they discovered bubbles forming within those dense gas clouds, some as large as the Milky Way.

These giant bubbles were moving away from the supermassive black holes at the centers, and in turn, the study claimed, seemed to prevent catastrophic cooling.

But this left open the question of how all that energy transfers into the gas around the bubbles.

In the new paper, researchers registered evidence of turbulence around the bubbles: swirls and eddies, that spin off smaller swirls and eddies, etc.

According to the theory, overtime, the chaotic movement reaches microscopic level and dissipates as heat.

“You can picture the bubble as a spoon that's stirring the hot tea," lead author of the study Yuan Li, an astrophysicist at the University of California, Berkeley, is quoted by Live Science as saying.

The turbulence was spotted by Li and her co-authors in data already available from the galaxy clusters Perseus, Abell 2597 and Virgo.

Filaments of cooler gas thread through the clouds at the centres of those galaxies, according to Li.

This high-resolution data allowed the team to chart the direction and of the gas and its speed at each point.

The resulting “heat map” offered proof of a clear pattern of turbulence.

"In a turbulence mode there's big eddies making little eddies making even smaller eddies. You've got a beautiful cascade," Li said.

The "beautiful cascade" appeared to show up in each galaxy cluster's centre.

"I didn't expect that, no one expected that," she said.

Brian McNamara, lead author of the paper mentioned previously and published in 2005 in Nature, who first suggested the bubbles might be warming these gases, has reservations about the new findings. He applauds the research as fascinating, but says:

"It's not conclusive to my mind. I'm not completely convinced."

Live Science quotes McNamara, chair of the Department of Physics and Astronomy at Canada's University of Waterloo, as saying the cascades Li and the team discovered don't quite match what one should expect from turbulence alone, suggesting other effects could be at work.

McNamara also pointed out that some theorists suspect turbulence may actually cool the gas more than it heats it.

Conceding that the study is a good paper with lots of good researchers involved, he summarised:

"I just think there's more work to be done."