The warm water, which is 2 degrees Celsius, is currently sitting underneath the Thwaites Glacier in the Western Antarctic Ice Sheet. The water was detected at the glacier’s grounding zone, which is “the place at which the ice transitions between resting fully on bedrock and floating on the ocean as an ice shelf and which is key to the overall rate of retreat of a glacier,” according to EurekaAlert.

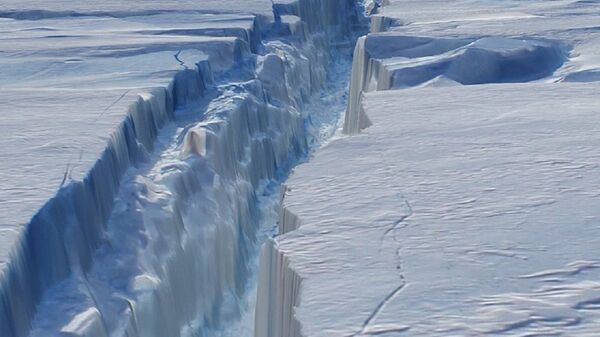

“So, this is coming from a very critical part of Antarctica. It’s called West Antarctica,” Rignot, who is also a professor of Earth system science at the University of California Irvine, told Loud & Clear host John Kiriakou on Friday. “The Thwaites glacier is 120 kilometers wide, and this giant glacier [is] responding to warmer waters. The [glacier is] … putting more ice into the ocean and rising sea levels. We are very concerned that processes of mass loss will accelerate with time,” Rignot explained, adding that glaciers in the Antarctic are “retreating inland almost as fast as they could.”

“The glaciers we are talking about in the Antarctic are retreating faster than any other glacier on the face of the Earth. These glaciers are retreating a kilometer a year,” Rignot said.

— BBC News (World) (@BBCWorld) January 28, 2020

"With the kayaks, we found a surprising signal of melting: Layers of concentrated meltwater intruding into the ocean that reveal the critical importance of a process typically neglected when modeling or estimating melt rates," lead study author Rebecca Jackson, a physical oceanographer and assistant professor in the Department of Marine and Coastal Sciences in the School of Environmental and Biological Sciences at Rutgers University-New Brunswick, is quoted as saying, Science Daily reported.

According to Rignot, melt rates can be calculated correctly from satellite data.

“That knowledge, however, has not been put in numerical models that are used to project sea level rise in the coming century. The reason for that is that the models haven’t had enough information to put those physical processes into the models,” Rignot explained.

To survey the ocean in the study, the researchers drilled a 600-meter-deep and 35-centimeter wide access hole in the ice and used and used an ocean-sensing device to measure the temperature of the water underneath the glacier’s surface.

“Drilling through that ice is not necessarily the most difficult thing to do with a hot water drill, but Thwaites is in a very remote location in the Antarctic. So, you have to take a lot of equipment,” Rignot explained.

“What happens to the glacier is that the glacier is not happy to sit in that warm, salty water. It’s melting away, and now we have data from the very location that matters the most, which is the grounding line. It doesn't matter if the warm water is 10, 20, 30 kilometers away. It matters if it’s right there at the feet of the glacier and melting it from below, and that’s what’s happening right now,” Rignot added.

According to Rignot, achieving zero net carbon emissions is not enough to stop the effects of global warming, although there is not much to do in the short term.

“Over the short term, we can mostly watch it happen. What we urgently need to do is get our hands on controlling the climate, making sure what is happening in Antarctica doesn’t get worse with time,” Rignot explained.

“And not only that, I am personally convinced that even zeroing our carbon emissions will not be sufficient for that. We will have to develop technology to sequester some of the carbon released in the atmosphere so that we can go back to some cooler climate conditions in the Antarctic, and that is going to take some time,” he said.

“If we take the effort to do that now, and it may take a few decades, it may take another few decades for the climate to react. So, it’s important to start planning and doing this now if we want to avoid some catastrophic future, 40, 50, 60 years from now.”