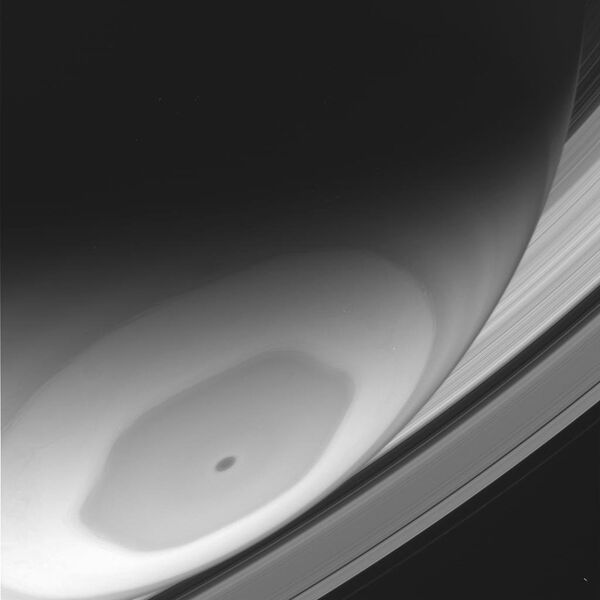

A new lab-tested atmospheric model - a highlight of a new study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences - suggests that a hexagon-shaped vortex that has been raging near Saturn's north pole goes very deep into its “crust”, possibly thousands of kilometres beneath.

The finding could help explain why the turbulent vibrations have remained quite stable since we first took note of the storm during the 1981 Voyager mission.

After the landmark Cassini probe, from 2004 to 2017, yielded a detailed front-row view of Saturn, the ringed planet’s zonal jets were found to retain their strength down to altitudes where the pressure could reach well over 100,000 bars.

Just to compare, light penetrates not much deeper than a single bar on Saturn, which means the vortices are deeper and more stable than one of the previously voiced hypotheses suggested - that the storms may have formed from shallow, alternating jets in the giant’s atmosphere.

The team started by working out a 3D model demonstrating deep thermal convection in the outer layers of gas giants, which can all of a sudden trigger giant polar cyclones, fierce alternating zonal flows, and a high-latitude eastward jet pattern.

In their simulations, a massive cyclone arose clinging to the north pole, while several smaller cyclones formed a strong eastward jet a bit north of the equator.

"A similar scenario can be imagined for Saturn where the hexagonal shape of the jet is sustained by adjacent six large vortices, which are hidden by the more chaotic convection in the shallower layers", the authors write.

This might be why some other models and earlier observations imply a more shallow jet presence in some parts of Saturn's hexagon, while, in fact, the truth lies much further down, the researchers believe. Much more atmospheric data is needed to underpin the conclusions about the cyclone formation and the shape of the vortices on the ringed gas mammoth.