A group of international researchers have spotted a fast-moving supermassive black hole, but have so far been unable to explain its untypical velocity, as the giant amount of matter roughly 3 million times heavier than our sun is storming through the centre of the galaxy J0437+2456 at 110,000 mph, or 177,000 km/h. Their fresh findings have been published in the Astrophysical Journal.

Such intense movement has hitherto been considered a rare occurrence since it would require a no less astonishing force to set it into motion.

"We don't expect the majority of supermassive black holes to be moving; they're usually content to just sit around," Dominic Pesce, study leader and astronomer at the Harvard and Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, said in a statement.

For starters, they drew parallels between the velocities of 10 supermassive black holes – objects in space so massive and dense that light could not escape it – and the galaxies, the centre of which they formed.

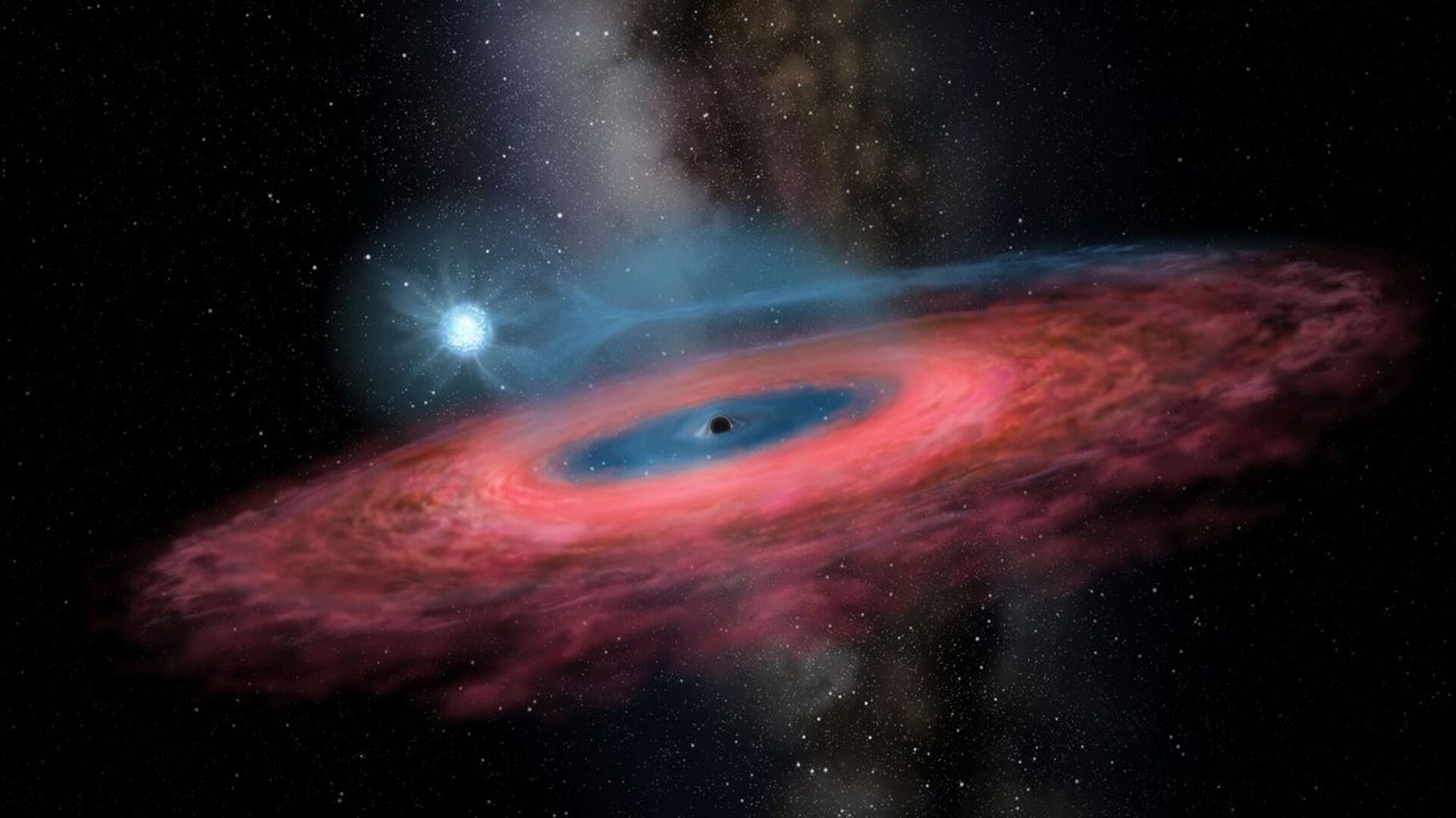

They went on to zero in on the black holes with water flowing inside their accretion disks, which look like spiral-shaped bunches of cosmic material encircling the black holes proper and spinning inward towards them. As water orbits a black hole, it bumps into other material, with electrons around the water’s hydrogen and oxygen atoms going wild and shooting to extremely high energy levels.

Whenever they calm down and return to their ground state, there occurs a laser-like beam of radio light, akin to microwave radiation, known as a maser.

Getting to the bottom of another cosmic phenomenon, known as red-shift, in which objects moving away have their light expanded to longer (and therefore redder) wavelengths, has led the scientists to determine to what the maser light from the accretion disk was shifted away from its known frequency when at rest, and thereby arrive at the speed of the moving black hole.

Of the 10 black holes they measured, nine were not moving, and one was in motion. Though 110,000 mph is pretty fast, it appears to be not the fastest supermassive black hole known to date. Scientists previously mapped a supermassive black hole zipping through space at 5 million mph (7.2 million km/h), as was reported in 2017 in the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics.

The researchers are still in the dark about what could have sent such heavy objects moving at such breakneck speeds, but there are two main theories with regard to the latest find. One is the merging of two supermassive black holes.

"The result of such a merger can cause the newborn black hole to recoil, and we may be watching it in the act of recoiling or as it settles down again," Jim Condon, a radio astronomer at the National Radio Astronomy Observatory, assumed.

The other possibility is arguably rarer and more novel, the researchers say, suggesting the supermassive black hole in question may be part of a duo with another black hole, which has been elusive enough to avoid being registered by telescopes.

"Despite every expectation that they really ought to be out there in some abundance, scientists have had a hard time identifying clear examples of binary supermassive black holes," Pesce commented.

"What we could be seeing in the galaxy J0437+2456 is one of the black holes in such a pair, with the other remaining hidden to our radio observations because of its lack of maser emission."