Afghan Allies One Year After US Withdrawal: Daring Escape to Europe, Hopeless Wait

08:11 GMT 13.08.2022 (Updated: 12:49 GMT 14.08.2022)

© AFP 2023 / BERTRAND GUAY

Subscribe

Longread

MOSCOW (Sputnik), Tommy Yang - On the eve of the one-year anniversary of the disastrous withdrawal of US forces from Afghanistan, a number of Afghan allies who were left behind shared with Sputnik their ordeals during the past year.

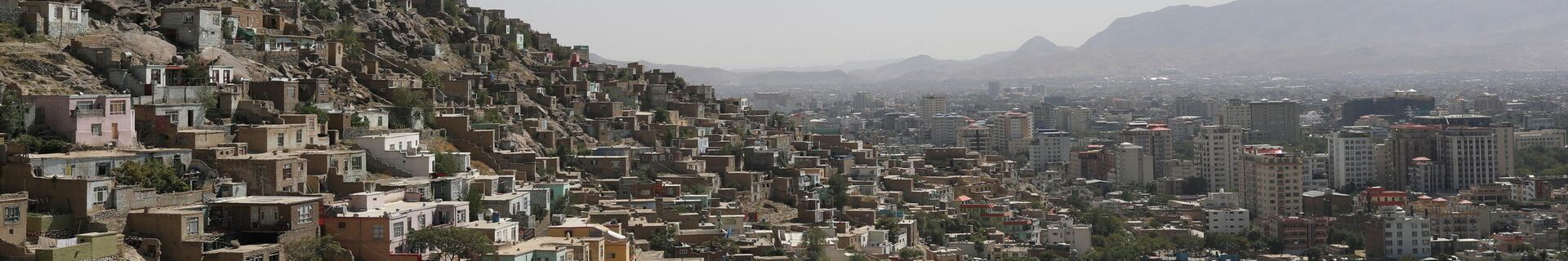

About one week before the Taliban (under UN sanctions for terrorist activities) took over Afghan capital Kabul in August last year, A., who only wished to be identified by the first letter of his last name, left his home in the middle of the night and embarked on a dangerous journey in hope of reaching Europe someday. Similar to many Afghans who worked closely with US-led coalition forces, A. believed that his over 10 years of experiences working on various projects funded by the US Department of Defense and the European Union Commission would make him an easy target for the Taliban.

With no time to waste, A. paid about $2,500 to a smuggler to help him get out of the country through the land border between Afghanistan and Iran. After hiking over 20 hours on foot through the mountainous border areas, A was able to reach Turkey after a brief stop in Tehran, Iran. But for many Afghans like A., who fled the country through the land border, Turkey was only the starting point of a long treacherous expedition towards Europe.

Stranded at Sea

After staying in Istanbul, Turkey for about three months without a job, A. boarded a boat in a desperate attempt to reach Italy through the Mediterranean Sea in November last year.

“I tried to reach Italy on a sailing boat. There were 45 people including women and children from Afghanistan, Iran and other Arabic countries in the Middle East. We started our journey from Izmir, Turkey to Italy. After five days and night, we arrived in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea when the control system of our sailing boat was damaged. Instead of moving towards Italy, the high wind and strong waves were pushing us towards Libya in Africa,” A., 34, said.

While they remained stranded at sea for over 4-5 hours, the situation on the sailing boat became more and more dangerous for the 45 migrants, as the waves were as high as 10 meters (about 33 feet) and the food supply was running low.

“We were in a really dangerous situation. And then we finally saw a cargo ship with a Turkish flag. That ship saw us and came close to try to rescue us. But the weather conditions were not good and the ship didn’t have proper equipment for the rescue. They couldn’t rescue us,” A. recalled.

After spending almost one week in the Mediterranean Sea, A. was sent to a detention center for migrants in Greece.

No Way Out on Land

After being held at the detention center for 25 days, Greek authorities told A. that if he did not choose to apply for asylum in Greece, he could be held under custody until there would be an agreement with the Afghan government for deportation.

“Without another choice, we accepted to apply for asylum. After 2-3 days, they freed us and transported us to a city named Larissa,” A said.

A. spent almost 5 months in Greece as he waited for his asylum application to be approved. According to A., some migrants tried to use fake travel documents to fly out, while others tried to cross the land border into North Macedonia.

“From North Macedonia into Serbia, and then Bosnia, Croatia, Slovenia, before reaching Italy eventually. But that route was very dangerous because it was very cold as it was the winter season,” he said.

A. also tried his luck once at the border with North Macedonia.

“It was Christmas Eve. I paid a human smuggler to help us move from Greece to Serbia for 800 Euros (about $815). There were three of us. He put us in the back of a cargo truck. But when the driver realized there were refugees in his truck, he called the police. The Macedonian police arrested us and took our finger prints, before deporting us back to Greece,” he said.

Truck Ride to Italy

With minimal chances of crossing the land borders in winter, A. decided to try his luck at sea once again to try to reach Italy.

But instead of paying human smugglers for another dangerous ride on a small boat, A. learned that it was possible to hide in cargo trucks that move from Greece to Italy.

“There were two commercial ports, Patras and Igoumenitsa. I chose Igoumenitsa because the distance to Italy was shorter. And it was also easy to climb over the fence to enter the port and hide ourselves in the cargo trucks. And there was a jungle next to the port. We could hide there in the day time. We could go to the city to charge our phones and power banks and eat at the restaurants. Everything was accessible to us,” A said.

5 September 2021, 21:44 GMT

Camped outside in the forest during the winter, A. started his numerous attempts to get into Italy by hiding inside a cargo truck. During his first several attempts, A. usually tried to get into the cargo trucks with assistance from human smugglers who would open the trucks and lock them in from outside. But as he was hiding inside the trucks before the check points, it was easy for the police or the truck driver to detect him when the truck was passing through the check point.

On his fifth attempt, A. found a new way of hopping over the fence to hide inside the trucks that had already went through the check points.

“For the fifth time, I found another away. At the back of the port, there was construction for the new port. At night, I climbed from that side. It was very hard because there were razor wires. But I managed to enter the port and there were three cargo ships that were docked there. There were about 30-40 trucks that had already completed the checks and waiting to be loaded into the ships. It was a good time for me to hide in one of those trucks,” he recalled.

Seven months after fleeing from Afghanistan, A. finally arrived in the Italian city of Bitonto on March 15.

Warm-Hearted Italians

The US decision to withdraw from Afghanistan forced the former quality control inspector at the Afghan Integrated Support Services to arrive in Italy as an illegal immigrant with only 300 Euros in cash.

“I went to the train station. But they wouldn’t sell me a ticket because I didn’t have any travel document or a negative COVID test result. So I searched on Google Maps and found a travel agency. There was a very nice girl inside. When I knocked on the door, she thought I was homeless and begging for money. She gave me two Euros. I told her that I was a refugee from Afghanistan. She told me: ’come inside and sit down.’ She gave me a cup of coffee. The Italian people are very good people. I love Italian people. They’re very supportive,” A. said.

After showing the girl at the travel agency his identification documents that he uploaded online earlier, A. was able to convince her to book him a train ticket to travel to Milan, where he hoped to move onto his final destination - Germany.

Before getting ready for his train at 9p.m. that night, A. updated his status on a social media account by sharing his new location in Italy. One of his former American supervisors saw his post and contacted him at once.

“He’s an American and his name is David Evertsen. He had a company in Florence, Italy. He had a contract with the Italian government. I saw my post and he called me asking:’ Where are you?’ I told him I wanted to go to Milan, after that to France. From France, I wanted to go to the UK or Germany. He told me to go to Florence first and sent me his address,” A. said.

Instead of going to Milan directly, A. went to Florence and stayed at this American friend’s home for about 20 days.

While A. was in Florence, his American friend contacted the US State Department and the US Ministry of Defense to check if there was any update on his application for the Special Immigrant Visa (SIV) for Afghans.

“He contacted everyone about my SIV application. But no one answered positively,” A said.

As there was still no legal means for him to move to the United States, A. decided to continue his journey to pursue a new life in Europe.

New Beginning in Germany

After leaving Florence, A. crossed from Genoa in Italy to Montpellier in France after paying 100 Euros to human smugglers and hiding in a cargo truck once again.

Once in France, A. went to stay at a friend’s home in Paris for about 10 days. During his stay in France, he learned that the British government planned to send illegal immigrants crossing into the country to Africa.

“I wanted to go to the UK. But they announced that if any refugee came from France illegally, they would send them to an African country named Rwanda. When I heard such news, I decided to go to Germany,” he said.

After paying another 120 Euros to a taxi driver in Paris, A finally arrived in Cologne, Germany on April 15. A. applied for asylum in Germany shortly after his arrival and was able to schedule an interview after one month. About three months after starting his application, A. was granted the status as a political refugee in Germany on July 20.

Looking back at his decision to embark on this dangerous journey to try to reach Germany, A. said he had no regrets despite all the hardships he went through.

“It was like a dream. But it was also a life and death matter. I freed myself from the Taliban. If I died on the way, it was better than living under the Taliban’s rule. During the 20 years of democracy in Afghanistan, I was the enemy for the Taliban. I worked against the Taliban. They rule the country right now. They’re still systematically eliminating us,” he said.

A. stressed that his adventure was also about the future of his children, not just himself.

“It’s not just about myself. I have children and they belong to the future. I need to try as much as possible for them, because they belong to the future. I need to invest in my children,” he said.

Thanks to A.’s efforts and despite the dangers he experienced during the past year, his family can reunite with him in 3-4 months after he receives his new German passport and sends them an official invitation.

Too Expensive to Go

In addition to the physical dangers A. had to go through, his journey from Afghanistan to Germany also carried a massive price tag.

“I paid about 14,000 Euros for this whole trip. That included the money to pay the human smugglers in different countries, as well as my living expenses during those eight months before I reached Germany. I paid for it from my savings when I worked for the coalition forces and I sold my Toyota car,” he said.

However, for other Afghan citizens who used to work for US funded projects, it would be very difficult to swallow such a huge price tag, especially if they had big families.

G., who only wished to be identified by the first letter of his surname, worked on various projects in support of the Bagram Air Base, which used to be the largest US military base in the country, from 2006 to 2016. He used the money he saved from working on those projects to open a convenient store next to the airport.

But when the US forces began to withdraw last year, G. did not have the luxury of sending his whole family on a similar journey out of the country like A. did. G. has five sons and three daughters. He only had enough money to send his oldest son to Turkey in August last year when the Taliban took over.

“My oldest son is 21 years old. He’s in Turkey now. But it’s also very hard there, because he just walked to Turkey through Iran like many others did. He didn’t not have a passport or a visa. He could be deported back any day, maybe today or tomorrow,” G, 48, said.

As his oldest son did not have any legal status in Turkey, he could only work in a clothing company and hide in his dormitory after work.

Struggle to Support Big Family

What worried G. more was how to support the rest of his family members, who were all stranded in Afghanistan.

“One year ago, I could make about 50,000 Afghani (about $550) every month. But I’m making half of that amount now, because everything became so expensive. The prices for rice, beans, sugar and everything else just went up by 10-15 times. I still run my shop, but there’s no money,” he said.

“I can make about 100 Afghani daily from my shop. But I need to spend 300-500 Afghani daily. It’s hard to take care of my family,” G said, while pointing to his youngest son, who was only 15 months old, during the video interview.

Similar to A.’s experiences in Turkey, G.’s oldest son also hoped to have a chance to reach Europe one day. But G simply did not have the financial means to support his son.

“My son told me more than 50 times:’ Please father, help me. I need to go from Turkey to Italy or Germany.’ But it’s hard. I need to have money for that. I tell him that I don’t money for that. I don’t even have money for my other kids,” he said.

G. said he had hoped his son could offer him some financial assistance after working in Turkey.

“Brother, if I tell you, you won’t believe me. I still haven’t received one dollar from my son. Maybe he makes $10 an hour in Turkey, but he also needs to spend all the $10 over there. He still hasn’t sent me anything. I tell him:’ You need to be sending me money for your brothers and your mother,’” he said.

Nevertheless, G. said his only hope was for his SIV application to go through and he could move with his whole family to the United States.

“If you help me 10% with SIV, if Furman and Robertson [his former US colleagues in Afghanistan] both help me 10%, maybe I can go early. Maybe in 5 months or one year. Then I need to sell my house. I don’t need this house. Maybe I’ll just give this house to my neighbor for free. I don’t need this house. I don’t need to come back,” he said.

After obtaining a letter from the US engineering company Fluor to prove his employment records, G. was able to submit his SIV application in August last year. Unfortunately, similar to many Afghan allies who worked closely with the US-led coalition forces, G. could only hope his SIV application would be approved one day in the future. Despite the Taliban’s promise to not seek retribution against Afghans who worked with US forces, both A. and G. did not believe the Taliban could keep their words in the long run.