https://sputnikglobe.com/20221023/tiny-worm-helps-find-means-to-protect-living-cells-from-cold-1102557748.html

Tiny Worm Helps Find Means to Protect Living Cells From Cold

Tiny Worm Helps Find Means to Protect Living Cells From Cold

Sputnik International

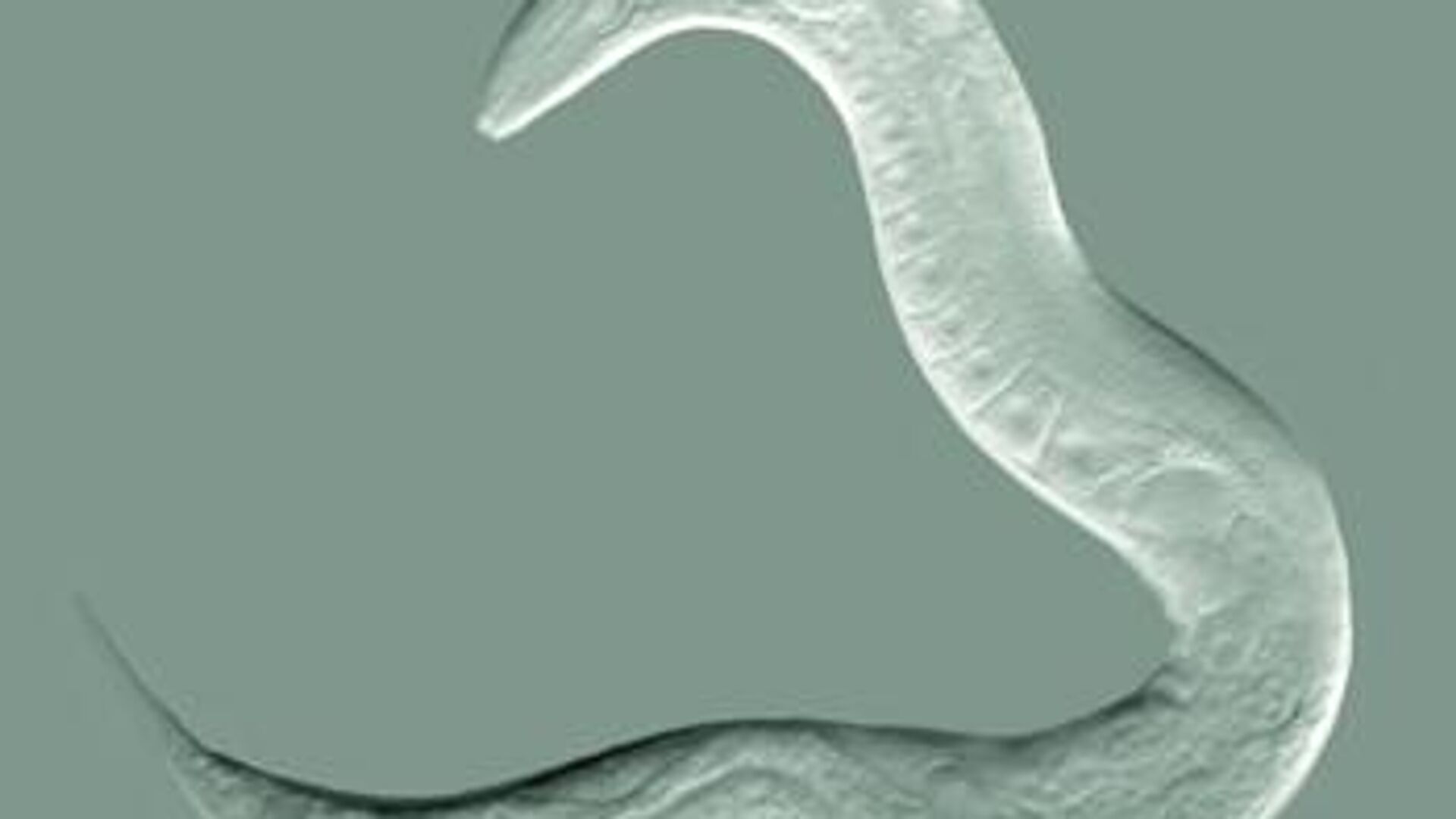

In their study, researchers used a tiny nematode and cultured neurons that can help fight diseases, travel in space and even challenge death. 23.10.2022, Sputnik International

2022-10-23T18:55+0000

2022-10-23T18:55+0000

2022-10-23T18:55+0000

science & tech

cooling

cells

protection

study

https://cdn1.img.sputnikglobe.com/img/07e6/0a/17/1102557935_0:50:350:247_1920x0_80_0_0_8c2c93584295c8d2375bdb6a87530030.jpg

A team of researchers in Norway has launched a project to study how living cells respond to deep cooling that may help treat trauma patients and perhaps even deal with neurodegenerative diseases, Phys.org has reported."This project began quite a few years ago as an ambitious masters' project, where the student wanted to work on something cool. Obliging, we began studying proteins involved in cold responses," said Rafal Ciosk, professor in the Section for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology at the University of Oslo’s Department of Biosciences.According to the media outlet, researchers used a nematode called Caenorhabditis elegans, which is widely used in biological research, to further their goals.Having kept these tiny worms at 4 degrees Celsius and then measured their lifespan, the team determined that they lived a week longer than creatures cultivated under the normal temperature.During the course of their work, researchers were able to determine that increasing the levels of a protein called ferritin, which stores iron, affords strong protection from the cold, and attempted to induce ferritin into mammalian cells such as neurons, which are very sensitive."We found that when we induced ferritin in these cells, and exposed them to cold, the ferritin had protective effects," Ciosk remarked.While the research in question may help efforts to discover means of using deep cooling to help trauma patients, it may also be relevant for treating neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer's and Parkinson's, the media outlet noted, with Ciosk remarking that they are “looking at cold-related degeneration” in the neurons they work with.

https://sputnikglobe.com/20220618/company-offers-customers-a-chance-to-be-brought-back-to-life-via-cryogenic-freezing-1096441810.html

Sputnik International

feedback@sputniknews.com

+74956456601

MIA „Rossiya Segodnya“

2022

Sputnik International

feedback@sputniknews.com

+74956456601

MIA „Rossiya Segodnya“

News

en_EN

Sputnik International

feedback@sputniknews.com

+74956456601

MIA „Rossiya Segodnya“

Sputnik International

feedback@sputniknews.com

+74956456601

MIA „Rossiya Segodnya“

science & tech, cooling, cells, protection, study

science & tech, cooling, cells, protection, study

Tiny Worm Helps Find Means to Protect Living Cells From Cold

In their study, researchers used a tiny nematode and cultured neurons that can help fight diseases, travel in space and even challenge death.

A team of researchers in Norway has launched a project to study how living cells respond to deep cooling that may help treat trauma patients and perhaps even deal with neurodegenerative diseases, Phys.org has reported.

"This project began quite a few years ago as an ambitious masters' project, where the student wanted to work on something cool. Obliging, we began studying proteins involved in cold responses," said Rafal Ciosk, professor in the Section for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology at the University of Oslo’s Department of Biosciences.

According to the media outlet, researchers used a nematode called Caenorhabditis elegans, which is widely used in biological research, to further their goals.

Having kept these tiny worms at 4 degrees Celsius and then measured their lifespan, the team determined that they lived a week longer than creatures cultivated under the normal temperature.

"It looked like they were hibernating, and this is something that has not been described for this organism before," Ciosk said. "We started looking at what happens in this organism and, while doing genetics on this model, we realized that there are certain manipulations we can do that make the survival of these animals in the cold even more effective."

During the course of their work, researchers were able to determine that increasing the levels of a protein called ferritin, which stores iron, affords strong protection from the cold, and attempted to induce ferritin into mammalian cells such as neurons, which are very sensitive.

"We found that when we induced ferritin in these cells, and exposed them to cold, the ferritin had protective effects," Ciosk remarked.

"We were able to show that we can use a very simple model system and identify cold-protective pathways that are conserved in mammalian cells. This could open new ways to treat hypothermia and potentially neurodegenerative conditions," he added.

While the research in question may help efforts to discover means of using deep cooling to help trauma patients, it may also be relevant for treating neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer's and Parkinson's, the media outlet noted, with Ciosk remarking that they are “looking at cold-related degeneration” in the neurons they work with.

"A couple of years ago, a study showed that certain cold-induced proteins have protective effects against various neurodegenerative diseases," he elaborated. "So, if you find how hibernators protect their neurons in the cold you may also find pathways that are relevant for patients."