https://sputnikglobe.com/20221031/a-look-at-artifacts-taken-by-colonialists-yet-to-be-returned-to-africa-1102867846.html

A Look at Artifacts Taken by Colonialists Yet to Be Returned to Africa

A Look at Artifacts Taken by Colonialists Yet to Be Returned to Africa

Sputnik International

African leaders have recently increased their calls for Europeans to return cultural heritage items stolen during the colonial era. However, Europeans are not... 31.10.2022, Sputnik International

2022-10-31T16:50+0000

2022-10-31T16:50+0000

2022-11-23T11:36+0000

africa

colonialism

artifacts

benin

benin bronze

west africa

https://cdn1.img.sputnikglobe.com/img/07e6/0a/1f/1102879324_0:77:3367:1971_1920x0_80_0_0_17a74b906da6246583ca08d39258c95a.jpg

During the colonial era, Europeans seized a large number of cultural artifacts from Africa, including diamonds, human remains, gold, silver, brass plates, and other valuables. As the era of colonialism came to an end, some European countries began to return artifacts to their historical homeland.For instance, the Natural History Museum in London and the University of Cambridge have recently agreed to collaborate with Zimbabwe in order to repatriate human remains of Zimbabwean origin that were seized during the colonial era.Nevertheless, many more African treasures are waiting to return home.Here is a list of some of the items taken from Africa by European colonizers.1. The Benin BronzesThe Benin Bronzes is a collection of several thousand brass plates with images from the palace of the ruler of Benin Empire in modern-day Nigeria, dating back to the 13th -16th centuries.The Benin Bronzes were seized by the British during a raid on the Kingdom of Benin in 1897. The British pillaged and burned the royal palace, stealing all of the royal treasures, including the bronzes. In retaliation for the assassination of several British officials, including Captain James Phillips, who demanded control of Benin's palm oil and rubber trade, the British also burned the kingdom to the ground.The majority of the treasures were auctioned off in London and are now scattered around the world in museums and private collections, including in the United States and Germany.Nowadays, despite a number of European countries having started to return Nigeria's bronzes, most of them remain abroad. This month, Lai Mohammed, Nigeria's minister of information and culture, urged the British Museum to return "stolen" Benin artifacts, emphasizing his ministry's formal request last year. The British Museum stated that due to UK law, repatriation is impossible.The British Museum is not the only place the minister sent his appeal to. The Benin Bronzes were scattered around the world as a result of auctions and donations, with some of them ending up in the United States and Germany, which agreed to return the artifacts.Mohammed thanked the Smithsonian Institution in the United States and the Foundation of Prussian Cultural Heritage in Germany for returning 29 and two Benin Bronzes respectively this year.2. The Great Star of Africa and Smaller Star of Africa The Great Star of Africa, the largest stone cut from the Cullinan diamond, was discovered in South Africa in 1905 in a mine owned by South African diamond magnate Thomas Cullinan. The enormous 530.2 carat drop-shaped diamond, also known as Cullinan I, was added to the Sovereign's Sceptre with Cross and is currently on public display in the Jewel House at the Tower of London. The Smaller Star of Africa, the second largest gem from the Cullinan stone and the fourth largest polished diamond in the world, is the most valuable stone in the British Imperial Crown.Both diamonds were taken from Africa during the colonial period.Meanwhile, the death of Queen Elizabeth II in early September was followed by demands for the return of the Great Star of Africa. The Royal Collection Trust, however, declined the request, claiming the diamond was presented to British monarchs "as a symbolic gesture to heal the rift between Britain and South Africa after the Boer War."3. The Ife HeadThe Ife Head is one of 18 copper alloy sculptures discovered in Ife, Nigeria, in 1938. Ife's head is believed to be a portrait of a ruler known as Uni or Oni from the 14th or 15th century AD. Ife's head was removed from Nigeria by H. Maclear Bate, the editor of the Daily Times of Nigeria, who most likely sold it to the National Art Collections Trust, which further donated it to the British Museum in 1939.The Ife head was stopped by British police amid an ongoing dispute between a Belgian antiques dealer and a Nigerian museum over its ownership.The Belgian antiques dealer reportedly bought it in a government sale. It’s unknown if he was aware of buying a stolen artifact, but formally he did nothing illegal and now retains his right not to relinquish his claim.In turn, the British police have remained neutral, explaining that no matter what their “private preference” is, the police “can't take property from an individual” and the dispute should “be resolved between the Nigerian government and the dealer”.Meanwhile, the dealer says he could sell the bronzes to the Nigerian government, while some Nigerians are outraged by the offer to pay for property initially stolen from them.4. Lusira's terracotta headLusira's terracotta head, one of the oldest sculptures discovered south of the Sahara, is thought to be around 1,000 years old. A.J. Wayland, a British geologist, excavated it and donated it to the British Museum.The Luzira Head, despite currently being displayed in the British Museum, “is still the property of Uganda,” authorities of the African country said this summer.5. A bronze bust of Queen IdiaA bronze bust of Queen Idia, mother of a medieval Benin ruler, was commissioned at the court in the early 16th century. Queen Idia played a key role in her son's successful military campaigns against rival tribes and factions. Therefore, after her death he ordered to make the Queen's busts and place them in front of the altars. The heads were designed to honor her military achievements. The Queen's bust was seized in the same British raid in 1897.In 1977, the Idia head was also the subjects of unsuccessful calls for repatriation. The calls were made ahead of the Second World Black and African Festival of Arts and Culture, where the Nigerian authorities wanted to exhibit the Idia head among other artIfacts.

africa

benin

west africa

Sputnik International

feedback@sputniknews.com

+74956456601

MIA „Rossiya Segodnya“

2022

News

en_EN

Sputnik International

feedback@sputniknews.com

+74956456601

MIA „Rossiya Segodnya“

Sputnik International

feedback@sputniknews.com

+74956456601

MIA „Rossiya Segodnya“

colonialism, artifacts, benin, benin bronze, west africa

colonialism, artifacts, benin, benin bronze, west africa

A Look at Artifacts Taken by Colonialists Yet to Be Returned to Africa

16:50 GMT 31.10.2022 (Updated: 11:36 GMT 23.11.2022) African leaders have recently increased their calls for Europeans to return cultural heritage items stolen during the colonial era. However, Europeans are not always eager to fulfill African requests for repatriation.

During the colonial era, Europeans seized a large number of cultural artifacts from Africa, including diamonds, human remains, gold, silver, brass plates, and other valuables. As the era of colonialism came to an end, some European countries began to return artifacts to their historical homeland.

For instance, the Natural History Museum in London and the University of Cambridge have recently agreed to collaborate with Zimbabwe in order to

repatriate human remains of Zimbabwean origin that were seized during the colonial era.

Nevertheless, many more African treasures are waiting to return home.

Here is a list of some of the items taken from Africa by European colonizers.

The Benin Bronzes is a collection of several thousand brass plates with images from the palace of the ruler of Benin Empire in modern-day Nigeria, dating back to the 13th -16th centuries.

The Benin Bronzes were seized by the British during a raid on the Kingdom of Benin in 1897. The British pillaged and burned the royal palace,

stealing all of the royal treasures, including the bronzes. In retaliation for the assassination of several British officials, including Captain James Phillips, who demanded control of Benin's palm oil and rubber trade, the British also burned the kingdom to the ground.

The majority of the treasures were auctioned off in London and are now scattered around the world in museums and private collections, including in the United States and Germany.

Nowadays, despite a number of European countries having started to return Nigeria's bronzes, most of them remain abroad.

This month, Lai Mohammed, Nigeria's minister of information and culture, urged the British Museum to return "stolen" Benin artifacts, emphasizing his ministry's formal request last year. The British Museum stated that due to UK law, repatriation is impossible.

The British Museum is not the only place the minister sent his appeal to. The Benin Bronzes were scattered around the world as a result of auctions and donations, with some of them ending up in the United States and Germany, which agreed to return the artifacts.

Mohammed thanked the Smithsonian Institution in the United States and the Foundation of Prussian Cultural Heritage in Germany for returning 29 and two Benin Bronzes respectively this year.

2. The Great Star of Africa and Smaller Star of Africa

The Great Star of Africa, the largest stone cut from the Cullinan diamond, was discovered in South Africa in 1905 in a mine

owned by South African diamond magnate Thomas Cullinan. The enormous 530.2 carat drop-shaped diamond, also known as Cullinan I, was added to the Sovereign's Sceptre with Cross and is currently on public display in the Jewel House at the Tower of London.

The Smaller Star of Africa, the second largest gem from the Cullinan stone and the fourth largest polished diamond in the world, is the most valuable stone in the British Imperial Crown.

Both diamonds were taken from Africa during the colonial period.

Meanwhile, the death of Queen Elizabeth II in early September was followed by demands for the return of the Great Star of Africa. The Royal Collection Trust, however, declined the request, claiming the diamond was presented to British monarchs "as a symbolic gesture to heal the rift between Britain and South Africa after the Boer War."

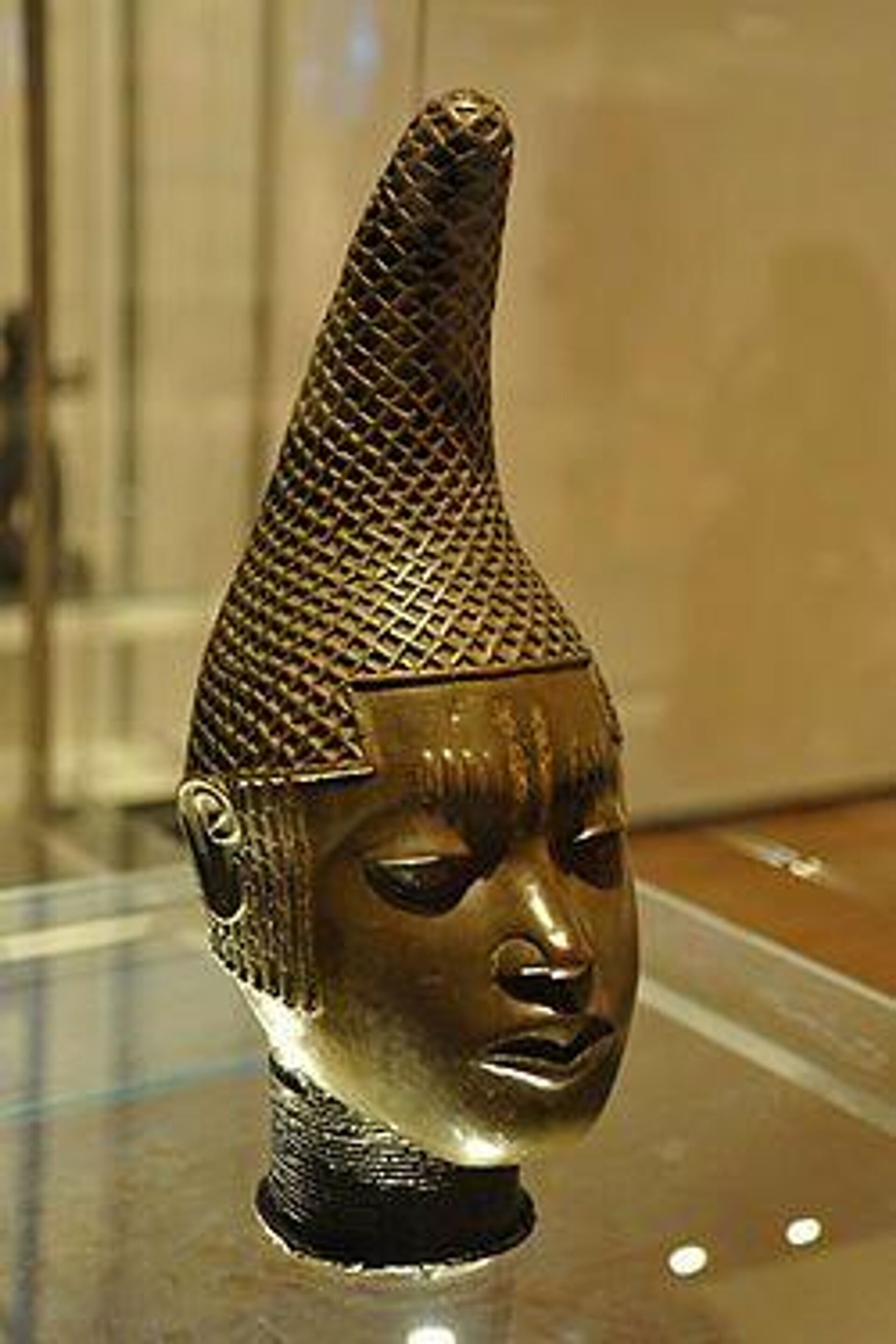

The Ife Head is one of 18 copper alloy sculptures discovered in Ife, Nigeria, in 1938. Ife's head is believed to be a portrait of a ruler known as Uni or Oni from the 14th or 15th century AD. Ife's head was removed from Nigeria by H. Maclear Bate, the editor of the Daily Times of Nigeria, who most likely sold it to the National Art Collections Trust, which further donated it to the British Museum in 1939.

The Ife head was stopped by British police amid an ongoing

dispute between a Belgian antiques dealer and a Nigerian museum over its ownership.

The Belgian antiques dealer reportedly bought it in a government sale. It’s unknown if he was aware of buying a stolen artifact, but formally he did nothing illegal and now retains his right not to relinquish his claim.

In turn, the British police have remained neutral, explaining that no matter what their “private preference” is, the police “can't take

property from an individual” and the dispute should “be resolved between the Nigerian government and the dealer”.

Meanwhile, the dealer says he could sell the bronzes to the Nigerian government, while some Nigerians are outraged by the offer to pay for property initially stolen from them.

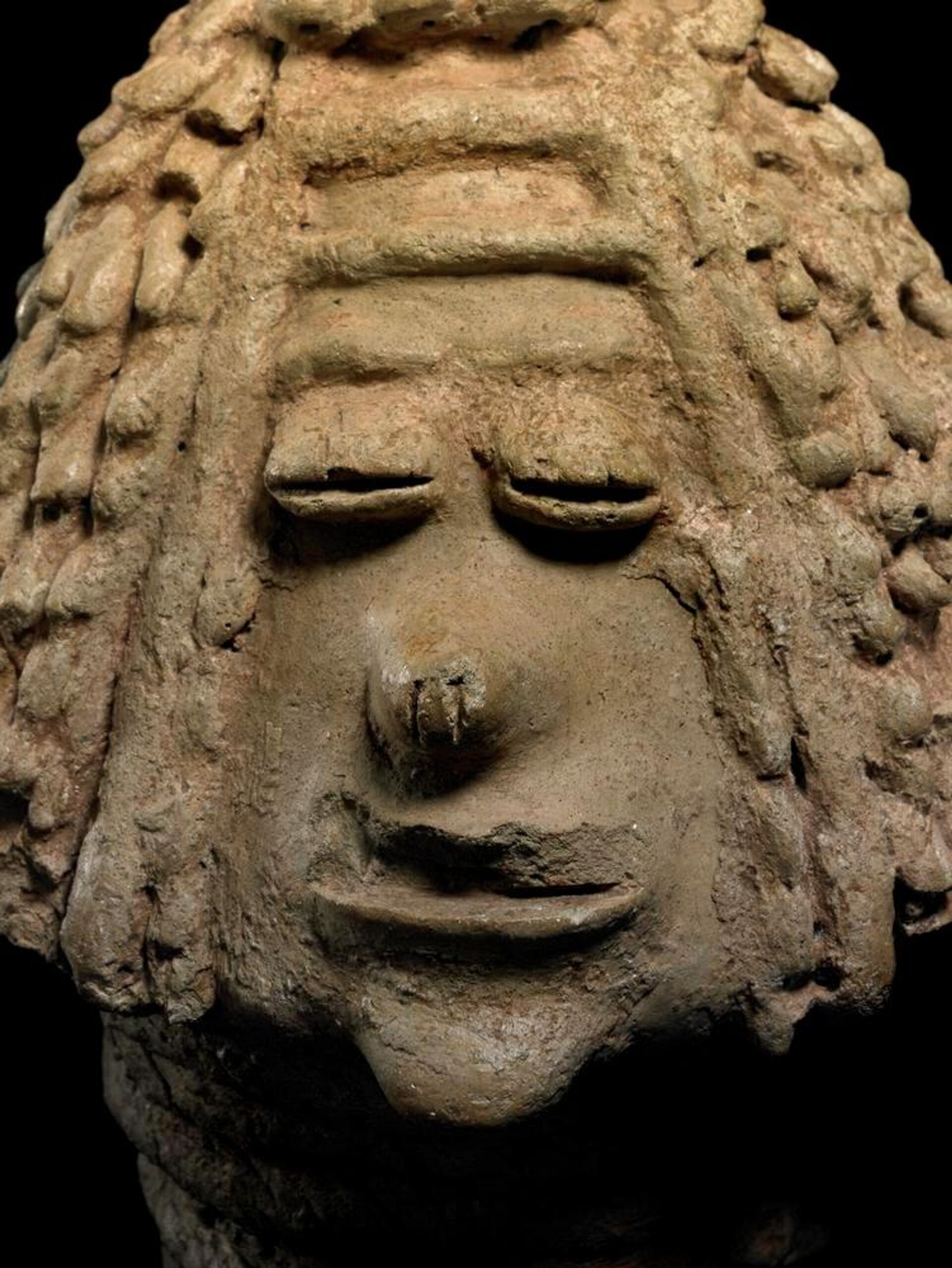

4. Lusira's terracotta head

Lusira's terracotta head, one of the oldest sculptures discovered south of the Sahara, is thought to be around 1,000 years old. A.J. Wayland, a British geologist, excavated it and donated it to the British Museum.

The Luzira Head, despite currently being displayed in the British Museum, “is still the property of Uganda,” authorities of the African country

said this summer.

5. A bronze bust of Queen Idia

A bronze bust of Queen Idia, mother of a medieval Benin ruler, was commissioned at the court in the early 16th century. Queen Idia played a key role in her son's successful military campaigns against rival tribes and factions. Therefore, after her death he ordered to make the Queen's busts and place them in front of the altars. The heads were designed to honor her military achievements. The Queen's bust was seized in the same British raid in 1897.

In 1977, the Idia head was also the subjects of unsuccessful calls for

repatriation. The calls were made ahead of the Second World Black and African Festival of Arts and Culture, where the Nigerian authorities wanted to exhibit the Idia head among other artIfacts.