https://sputnikglobe.com/20230710/crunch-deep-sea-mining-talks-resume-amid-growing-global-hunger-for-rare-minerals-1111790993.html

Crunch Deep-Sea Mining Talks Resume Amid Growing Global Hunger For Rare Minerals

Crunch Deep-Sea Mining Talks Resume Amid Growing Global Hunger For Rare Minerals

Sputnik International

Representatives of 168 member states of the International Seabed Authority (ISA) have converged in Kingston, Jamaica to debate the contraversial issue of deep-sea mining.

2023-07-10T15:58+0000

2023-07-10T15:58+0000

2023-07-10T15:58+0000

beyond politics

deep-sea

international seabed authority

science & tech

https://cdn1.img.sputnikglobe.com/img/07e7/07/0a/1111790292_0:160:3072:1888_1920x0_80_0_0_8e338f81b312aca23a4c1879604bd57a.jpg

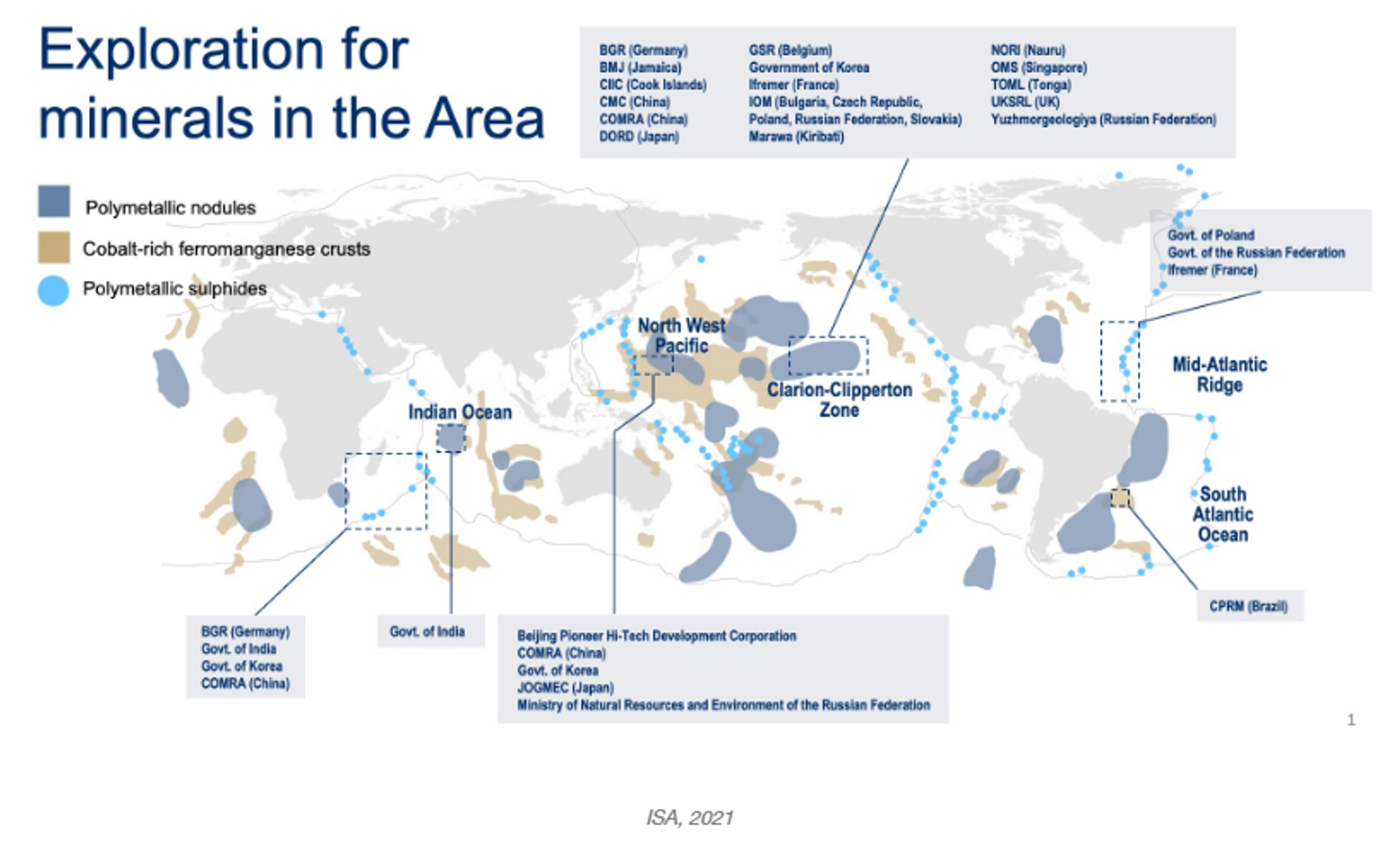

The contraversial issue of deep-sea mining is once again in the headlines, as representatives of 168 member states of the International Seabed Authority (ISA) converge in Kingston, Jamaica. Throughout the meeting, set to continue until July 28, an attempt will be made to hammer out the world's first potential operating guidelines for the process of harvesting metals from the seabed. Proponents of deep-sea mining have argued for decades that minerals found in the seafloor could be a promising source of metals crucial for various “green” technologies. The demand for rare earths has been rapidly accelerating, largely driven by growing electrification of industry, transport, and utilization of wind power in turbines. Rare earth elements (REE) is a collective term used in respect to 17 minerals used in modern laser, medical, defense, and electronics technologies, as well as in communication devices.However, numerous scientists and eco-activists have been arguing that deep-sea mining could threaten the biodiversity of vital ecosystems, pointing to the fact that not enough is known about the life that the seafloor is teeming with.Since 2001, the International Seabed Authority - the United Nations body responsible for regulating deep-sea mining – issued 31 permits to explore the ocean floor. But these permits apply to international waters, with countries free to conduct exploration in their own national waters. This is what Norway announced it was doing in June. It opened huge areas in the Greenland Sea, Norwegian Sea, and the Barents Sea for mining companies to apply for licenses, pointing to data showing deposits of copper, cobalt, and rare earths such as neodymium and dysprosium. Norway's own environment agency has strongly opposed the plan, with objections also pouring in from fishermen and environmentalists, concerned over the possibility of toxic heavy metal particles being released in the process.After the Pacific nation of Nauru in Micronesia went further, and formally applied for a commercial licence to begin deep sea mining in 2021, a two-year clause was set in place to grant the ISA much-needed leeway to assemble some sort of environmental regulation rulebook to rely on.Throughout these two years, there has been growing opposition to deep-sea mining, with around 200 countries, such as Germany, Spain, and Switzerland calling for a moratorium on the harvesting of marine rocks due to environmental concerns. The European Academies Science Advisory Council has warned of the “dire consequences” for marine ecosystems, and lambated what it called the “misleading narrative” of the vital importance of deep-sea mining for metals needed to transition to a low-carbon economy. Warnings that potential techniques to harvest the minerals from the seabed could be fraugh with noise, light pollution, and other factors detrimental to marine species were issued by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN).

https://sputnikglobe.com/20230609/can-norways-deep-sea-mining-bid-fuel-eus-faltering-green-transition-1111025223.html

https://sputnikglobe.com/20230621/black-day-for-norwegian-nature-as-oslo-plans-to-open-its-waters-for-deep-sea-mining-1111352038.html

Sputnik International

feedback@sputniknews.com

+74956456601

MIA „Rossiya Segodnya“

2023

News

en_EN

Sputnik International

feedback@sputniknews.com

+74956456601

MIA „Rossiya Segodnya“

Sputnik International

feedback@sputniknews.com

+74956456601

MIA „Rossiya Segodnya“

deep-sea mining, rare earth metals, green transition, marine biodiversity, marine ecosystems

deep-sea mining, rare earth metals, green transition, marine biodiversity, marine ecosystems

Crunch Deep-Sea Mining Talks Resume Amid Growing Global Hunger For Rare Minerals

The Jamaica-based intergovernmental body, the International Seabed Authority (ISA), is meeting on July 10 - 28 in an attempt to rekindle controversial negotiations over proposals to allow commercial deep-sea mining after the expiry of what has been, in effect, a two-year moratoriom on the practice.

The contraversial issue of

deep-sea mining is once again in the headlines, as representatives of 168 member states of the

International Seabed Authority (ISA) converge in Kingston, Jamaica. Throughout the meeting, set to continue until July 28, an attempt will be made to hammer out the world's first potential operating guidelines for the process of harvesting metals from the seabed.

Proponents of deep-sea mining have argued for decades that minerals found in the seafloor could be a promising source of metals crucial for various “green” technologies. The demand for rare earths has been rapidly accelerating, largely driven by growing electrification of industry, transport, and utilization of wind power in turbines.

Rare earth elements (REE) is a collective term used in respect to 17 minerals used in modern laser, medical, defense, and electronics technologies, as well as in communication devices.

However, numerous scientists and eco-activists have been arguing that deep-sea mining could threaten the biodiversity of vital ecosystems, pointing to the fact that not enough is known about the life that the seafloor is teeming with.

Since 2001, the

International Seabed Authority - the United Nations body responsible for regulating deep-sea mining – issued 31 permits to

explore the ocean floor. But these permits apply to international waters, with countries free to conduct exploration in their own national waters. This is what Norway

announced it was doing in June. It opened huge areas in the Greenland Sea, Norwegian Sea, and the Barents Sea for mining companies to apply for licenses, pointing to data showing deposits of copper, cobalt, and rare earths such as neodymium and dysprosium. Norway's own environment agency has strongly opposed the plan, with objections also pouring in from fishermen and environmentalists, concerned over the possibility of toxic heavy metal particles being released in the process.

After the Pacific nation of Nauru in Micronesia went further, and formally applied for a commercial licence to begin deep sea mining in 2021, a two-year clause was set in place to grant the ISA much-needed leeway to assemble some sort of environmental regulation rulebook to rely on.

Throughout these two years, there has been growing opposition to deep-sea mining, with around 200 countries, such as Germany, Spain, and Switzerland calling for a moratorium on the harvesting of marine rocks due to environmental concerns.

The

European Academies Science Advisory Council has warned of the “

dire consequences” for marine ecosystems, and lambated what it called the “

misleading narrative” of the vital importance of deep-sea mining for metals needed to transition to a low-carbon economy. Warnings that potential techniques to harvest the minerals from the seabed could be fraugh with noise, light pollution, and other factors detrimental to marine species were issued by the

International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN).