‘Cruel Realities’ Await US Partners in Anti-China Semiconductor Trade Wars

© Sputnik / Alexei Kudenko

/ Subscribe

A South Korean lawmaker and former executive at tech manufacturing giant Samsung has sharply criticized US attempts to push Asian partners into restricting their tech industries from trading with Chinese firms, warning it could not only disrupt the markets, but even backfire and turn countries against Washington.

"If [Washington] continues to try to punish other nations and to pass bills and implement ‘America First’ policies in an unpredictable manner, other countries could form an alliance against the US," Yang Hyang-ja, a member of South Korea’s National Assembly and founder of the centrist Hope of Korea party, told a British business daily in a Sunday interview.

"The US should abandon its current approach of trying to get something out of shaking and breaking the global value chain," she added.

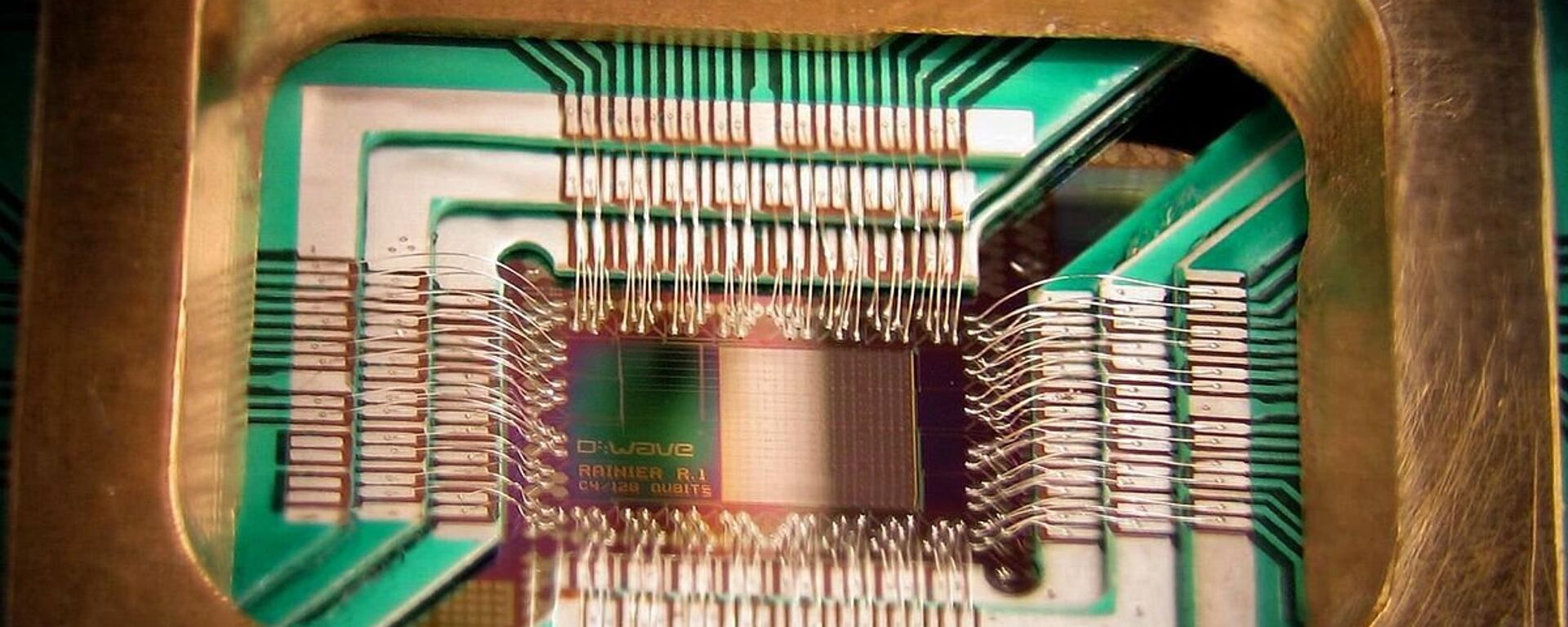

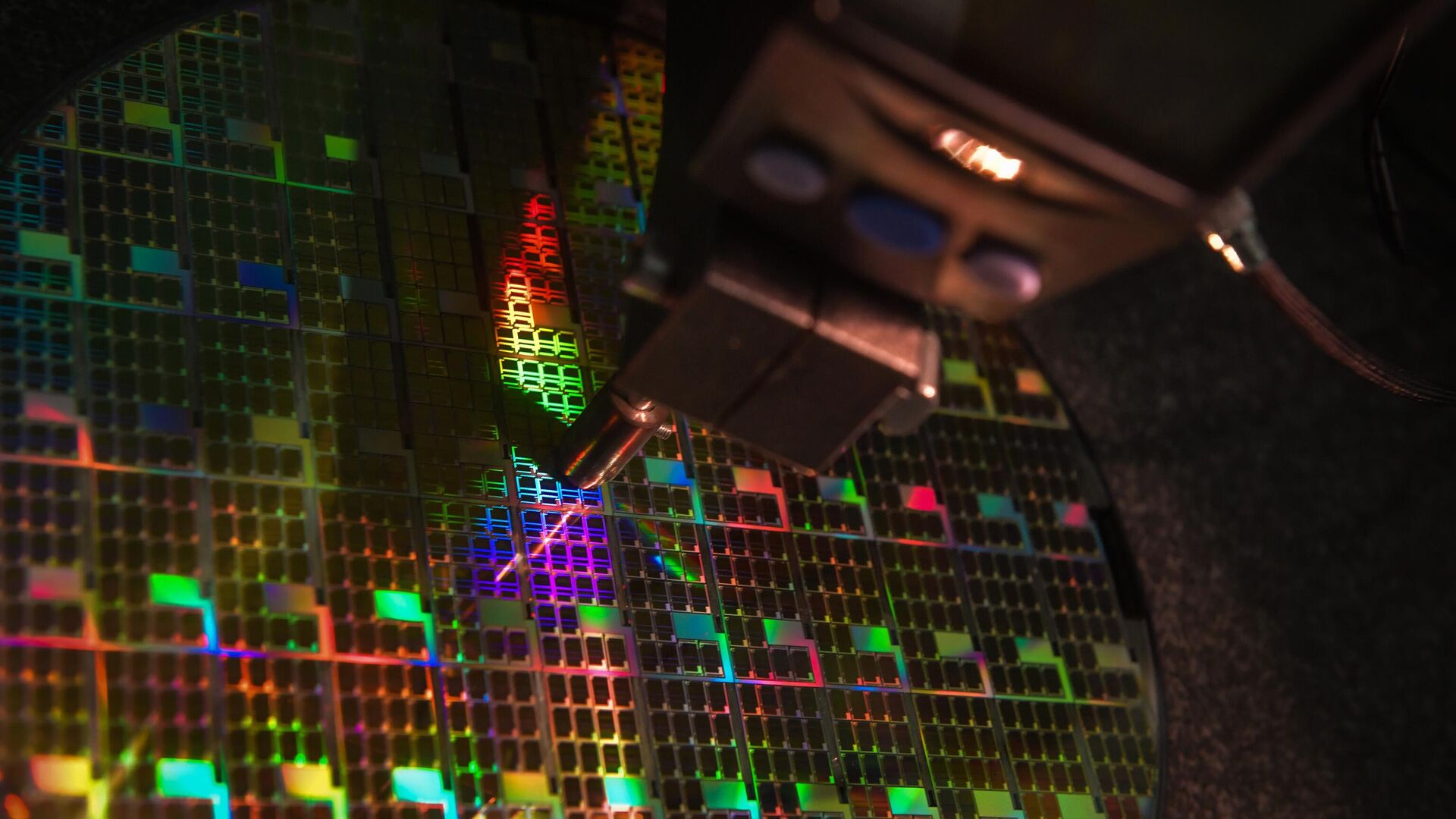

The US has blacklisted dozens of Chinese tech firms in recent years, blocking US companies from trading with them and pushing other governments to adopt similar measures. South Korea, Japan, the Netherlands, and the government in Taiwan have especially been pushed to curb the exports of high-end semiconductors and microchips to China, as well as the advanced methods used to manufacture them. US lawmakers have also adopted extensive subsidies for US chipmakers as well as firms based in the above-mentioned partners who are willing to move some of their operations to US soil.

According to Washington, these measures are aimed at denying Chinese government and military-related firms access to tech on par with that used by the West, as well as securing supply chains from possible interference by Beijing, including the possibility that a future war between the US and China might disrupt the flow of tech products into Western markets. However, they are often sold to the public as attempts to crack down on China’s supposedly “unfair” and “anti-market” practices by subsidizing its tech companies.

Professor Gary Hufbauer, a senior fellow and trade expert at the Peterson Institute for International Economics in Washington, DC, told Sputnik that while Yang’s warning was “not a current reality, in a few years the pushback could get stronger. Over the long term, say five years, I am skeptical that Asian partners will follow strict US controls on trade with China.”

He described the perspective of HSBC Holdings public affairs chief Sherard Cowper-Coles, who criticized US policy as harmful to British business interests and criticized Downing Street for supporting it, as “a minority view” right now.

“But I expect it will gain strength if the US imposes sanctions on firms in allied countries,” he added.

“The core message, especially to South Korea and Taiwan, is that they should align their own semiconductor trade and investment restrictions, with respect to China, to the US template,” Hufbauer said.

The expert said that while so far the effect of restrictions on Asia’s technological sector has been “limited,” the effects will be more fully felt in the next two years.

“All fabs, chip designers, and equipment manufacturers are affected by US restrictions. All told, that’s about a dozen firms outside of China. Given the huge capital costs to enter the industry, and the shortage of skilled personnel, I don’t expect many new firms to emerge in the next few years.”

Dr Victor Teo, a political scientist who specializes in the International Relations of the Indo-Pacific, told Sputnik there had already been “a broad increase” in tech prices across Asia, but it was unclear if the cause was US policies or the near-global inflation of recent years.

“I think most of the major chipmakers, alongside the Netherlands companies who supply China with chip-making machines and tools, are very concerned. Putting in measures to restrict China might slow Beijing’s access to the advanced chips, but at the same time has spurred a techno-nationalistic response from Beijing instead as it doubled down its efforts to spur its domestic chipmaking capabilities. While it is not clear to what extent the Chinese have caught up (this depends on how we define the term “catching up”), the open consensus is that the Chinese are closing the technological gap with Korean and Taiwanese producers.”

“The recently announced export control of critical materials for semiconductors, such as gallium and germanium, will, in the same spirit of reciprocity, create problems for the United States and its allies. This would mean that Chinese domestic companies would gain an advantage to become peer competitors to the existing chipmaking giants, even as the latter would lose access to the Chinese market. The profits from China that are instrumental for the innovation and research and development (R&D) in the development of the next generation of chips would no longer be available.”

“In the long run, unless these existing chip making companies can overcome this problem, there will also be consequences for the United States and its allies.”

Teo noted that as a semiconductor expert, Yang was “principal” in Samsung’s rise, and that she feels that US policies will “hollow out” Samsung and the ability of Korean industries as a whole to compete with China in the future, to say nothing of their existing rivals like Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TMSC) that are relocating to the US.

“Yang feels that it is in South Korea’s interests to counter this trend to ensure Korea retains this indigenous capability. There are signs that Japan is also becoming very vested in investing and building up its indigenous capability.”

“I do not think there will be an anti-US club forming amongst the US allies as the elites in these countries are mostly very pro-America,” Teo said. “The question is if more of these elites would wake up to the possible cruel realities of alliance politics and calibrate these costs against their national interests to make better judgment in their national policies.”

Turning to Cowper-Coles’ criticisms, Teo called it emblematic of a divide that exists in many countries between the business community and firms tied to politics and the military-industrial complex.

“Across the board, it is likely that those who are interested in businesses are more likely to stand on the side of globalization and better bilateral relations than those whose job is to engage in nationalistic politics or strategic planning which often involve defining enemies, real or imagined,” he noted.

Dr. Kiyul Chung, a political analyst, editor-in-chief at The Fourth Media, and a retired Professor of Tsinghua University, told Sputnik that Washington’s anti-Chinese tech policies were typical of its “bully, imperial, or gangster-like” behavior since its formation.

“The US literally corrals or forces ‘other Asian partners’ to dare not to go out of that ‘[rules-based international] order‘, which means ‘you better join the US to isolate and eventually impede, weaken, or kill the Chinese semiconductor industry,’” he said.

Chung predicted that the chip industries in Taiwan and Japan could soon befall the fate of South Korea.

“That can happen at any moment. Even ‘a century-long pro-West’ and pro-US vassals such as Japan and Taiwan can be also targeted at any moment if any of them is not in line to strictly follow the orders coming from Washington. As is well-known, none of the above-mentioned three Asian Chip powers are politically, economically, militarily, and even culturally independent thereby sovereign at all.”

Chung characterized Yang’s “extraordinarily independent-minded and strong-willed” behavior as “a genuine act of political revolt, daring to challenge her colonial master.”

The former professor said that the “defiant, undeterred, and anti-imperialist positions, stances, or principles” of Russia and China could create room for Asian politicians and companies to stand up to Washington.

“If Russia and China stay the course, Ms. Yang’s courageous challenge can be interpreted as a signal or sign that her sentiment is not an isolated act. It’d be a broadly-shared dissatisfaction among the global corporations such as Samsung and other big corporations in Seoul with regard to their survival as a business. However, her political revolt can be eventually subdued or dismissed if she doesn’t or won’t be able to generate sociopolitical support enough within South Korean society.”