https://sputnikglobe.com/20231109/universes-oldest-galaxies-give-off-extreme-glow-thanks-to-unique-radiation-1114855327.html

Universe’s Oldest Galaxies Give Off ‘Extreme’ Glow Thanks to Unique Radiation

Universe’s Oldest Galaxies Give Off ‘Extreme’ Glow Thanks to Unique Radiation

Sputnik International

Astronomers studying data from the JWST's Advanced Deep Extragalactic Survey, which looks at early galaxies with an infrared lens to help analyze their spectra, may have found an explanation for a situation that shouldn’t exist.

2023-11-09T22:25+0000

2023-11-09T22:25+0000

2023-11-09T22:24+0000

beyond politics

james webb space telescope (jwst)

universe

astronomy

stars

big bang

https://cdn1.img.sputnikglobe.com/img/07e7/08/03/1112359811_0:156:3000:1844_1920x0_80_0_0_c660ea78130e4bde9ca67f0ab4def6a9.jpg

Astronomers studying data from the JWST's Advanced Deep Extragalactic Survey, which looks at early galaxies with an infrared lens to help analyze their spectra, may have found an explanation for a puzzling situation that, by all prevailing logic, shouldn’t exist.When the Big Bang released all the matter in the universe from a compact sphere some 13.8 billion years ago, allowing it to expand exponentially, there was a certain sequence of events that had to take place before the universe could begin to look like what we see today, with galaxies and stars that shine and black holes that gobble up light. According to astrophysicists’ understanding of these events, it took a while for the first stars and galaxies to form, as much of the universe’s matter was diffuse and not compacted into regions like nebulae, which form from exploding stars and are regarded as stellar nurseries. As a result, the early universe wasn’t nearly as bright as it is at present.At least, that’s what they thought. When the JWST looked at a group of galaxies 12 billion light-years away (and thus existing 12 billion years in the past), they found an “extreme” glow of light, equivalent to galaxies much larger than them.A study explaining how and why these galaxies, and 90% of early galaxies, have "extreme emission features" has been accepted for publication in The Astrophysical Journal.What they found was that the surrounding gas, typically inert, was being “excited” by radiation from the relatively small number of new stars in the galaxy, dramatically amplifying the light the galaxy as a whole was giving off.When scientists looked at newer stars, they found just 1% that exhibited these once-common properties. "The chemical elements that make up everything tangible on Earth and the universe, except hydrogen and helium, originated in the cores of distant stars," Gupta said. "So, it is critical to understand the conditions surrounding galaxies and stars in the early universe for us to better understand our own world today."

https://sputnikglobe.com/20231109/photo-webb-hubble-telescopes-join-forces-to-make-panchromatic-image-of-galaxy-cluster-1114854668.html

universe

Sputnik International

feedback@sputniknews.com

+74956456601

MIA „Rossiya Segodnya“

2023

News

en_EN

Sputnik International

feedback@sputniknews.com

+74956456601

MIA „Rossiya Segodnya“

Sputnik International

feedback@sputniknews.com

+74956456601

MIA „Rossiya Segodnya“

james webb space telescope, nasa photos, astronomy, early universe, how old is the universe

james webb space telescope, nasa photos, astronomy, early universe, how old is the universe

Universe’s Oldest Galaxies Give Off ‘Extreme’ Glow Thanks to Unique Radiation

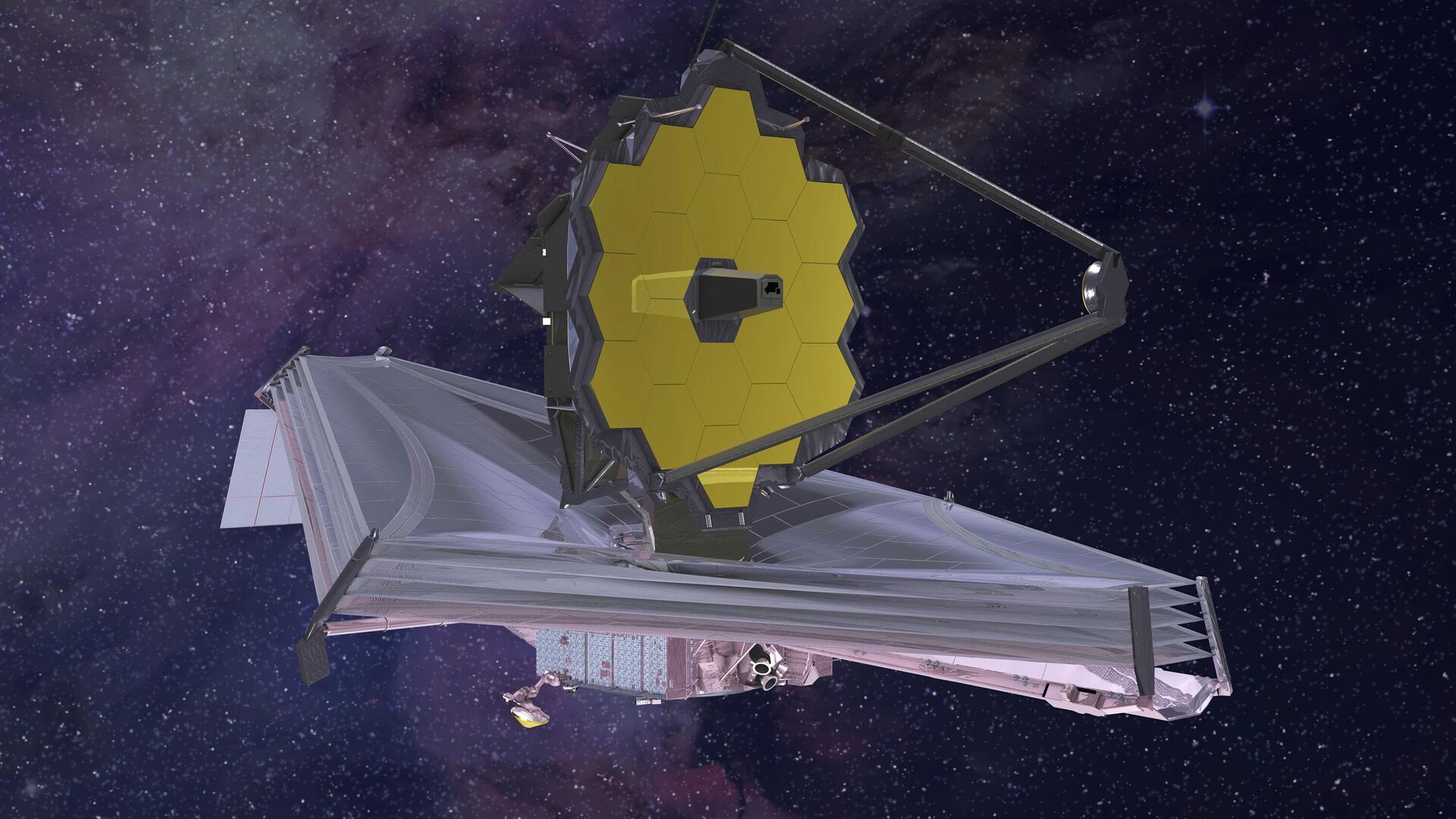

The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), placed in a distant Earth orbit, is uniquely capable of peering back into the early universe by viewing the most distant objects ever seen by humans. The latest discovery made using the JWST has once again upended scientists’ theories about how events unfolded in the early universe after the Big Bang.

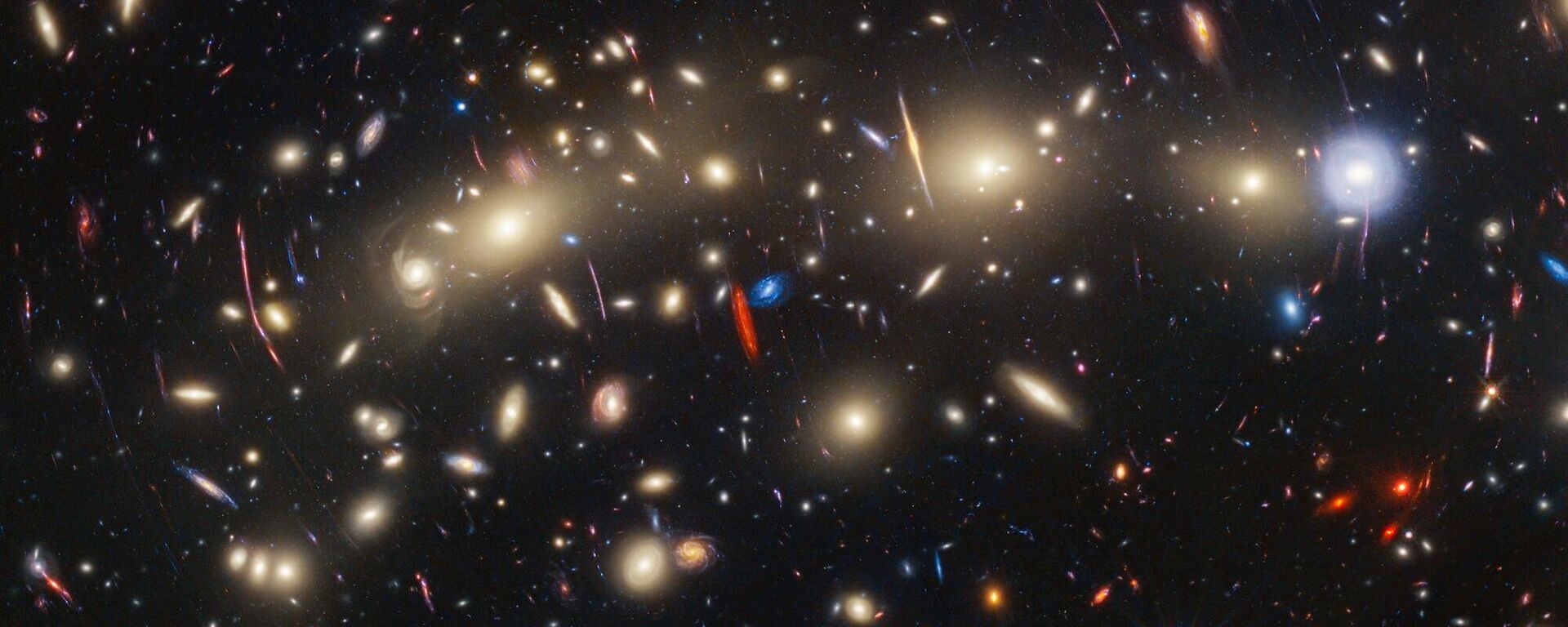

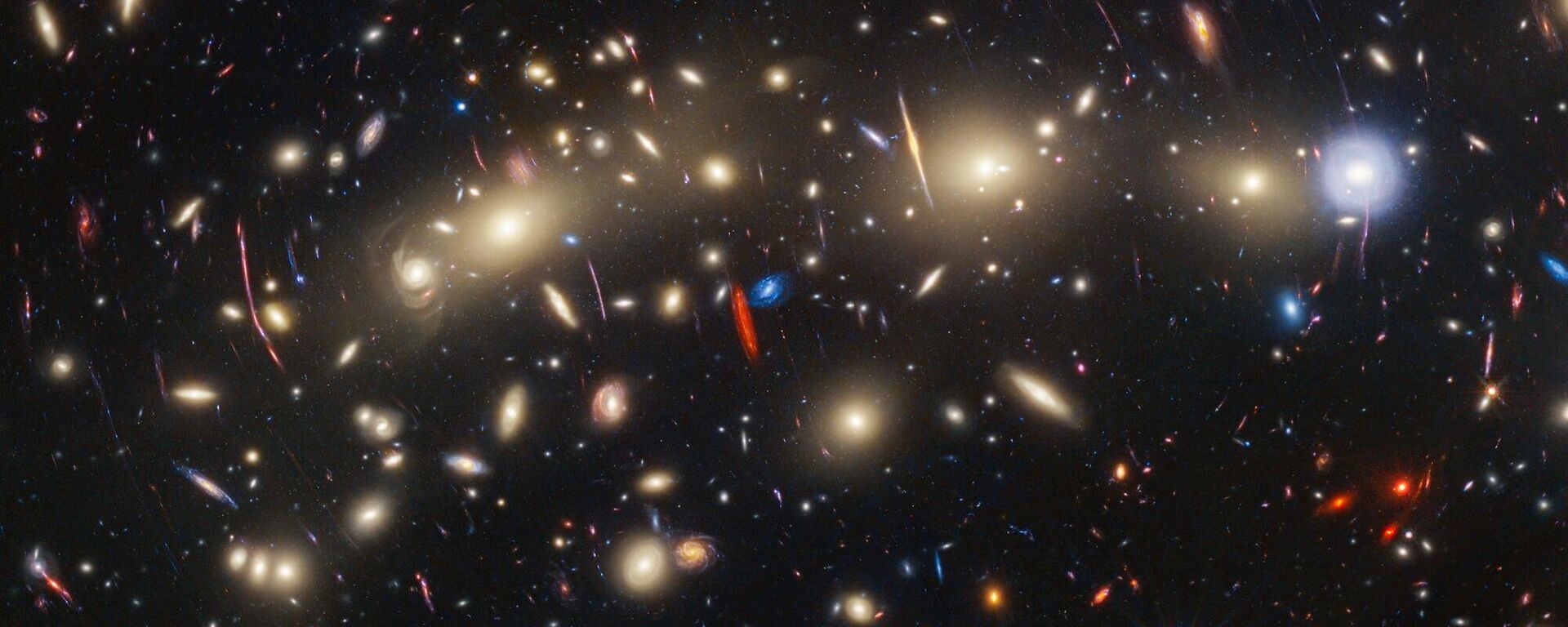

Astronomers studying data from the JWST's Advanced Deep Extragalactic Survey, which looks at early galaxies with an infrared lens to help analyze their spectra, may have found an explanation for a puzzling situation that, by all prevailing logic, shouldn’t exist.

When the Big Bang released all the matter in the universe from a compact sphere some 13.8 billion years ago, allowing it to expand exponentially, there was a certain sequence of events that had to take place before the universe could begin to look like what we see today, with galaxies and stars that shine and

black holes that gobble up light.

According to astrophysicists’ understanding of these events, it took a while for the

first stars and galaxies to form, as much of the universe’s matter was diffuse and not compacted into regions like nebulae, which form from exploding stars and are regarded as stellar nurseries. As a result, the early universe wasn’t nearly as bright as it is at present.

At least, that’s what they thought. When the JWST looked at a group of galaxies 12 billion light-years away (and thus existing 12 billion years in the past), they found an “extreme” glow of light, equivalent to galaxies much larger than them.

9 November 2023, 21:23 GMT

A

study explaining how and why these galaxies, and 90% of early galaxies, have "extreme emission features" has been accepted for publication in The Astrophysical Journal.

"Our paper proves that interactions with the neighboring galaxies are responsible for the unusual brightness of early galaxies," Anshu Gupta, an astrophysicist at Curtin University in Australia and lead author of the study, told US media. "The explosion of star formation triggered by the interactions could also explain the more massive nature of early galaxies."

What they found was that the

surrounding gas, typically inert, was being “excited” by radiation from the relatively small number of new stars in the galaxy, dramatically amplifying the light the galaxy as a whole was giving off.

"Gas cannot emit light on its own," Gupta said. "But the young, massive stars emit just the right type of radiation to excite the gas - and the early galaxies have lots of young stars."

When scientists looked at newer stars, they found just 1% that exhibited these once-common properties. "The chemical elements that make up everything tangible on Earth and the universe, except hydrogen and helium, originated in the cores of distant stars," Gupta said.

"So, it is critical to understand the conditions surrounding galaxies and stars in the early universe for us to better understand our own world today."