Source of Egyptian Artifacts Found in Scotland Seven Decades Ago Finally Revealed

04:02 GMT 26.11.2023 (Updated: 10:19 GMT 26.11.2023)

© National Museums Scotland

Subscribe

Ancient Egyptian relics and sculptures that were found in the yard of a school in Scotland 71 years ago were a source of mystery until recently. Archeologists had little difficulty identifying their origin and meaning, but what puzzled them was when they were brought there and by whom.

The first discovery at the Melville House was made by a schoolboy in 1952 who was digging in the yard for potatoes as a form of punishment. It was an Egyptian statue carved out of red sandstone. Another artifact, a bronze statuette of the Apis bull was unearthed in 1966. But in 1984, a group of boys found an Egyptian bronze figurine in the yard and brought it to a museum leading to an excavation that unearthed more artifacts, bringing the total to 18.

Among them are part of a statuette of the Egyptian Goddess Isis suckling her son Horus and a ceramic plaque with the eye of Horus.

Scientists were able to date the artifacts from 1069 B.C. to 30 B.C. but how they ended up in Scotland and buried in the yard remained a mystery.

1/4

© National Museums Scotland

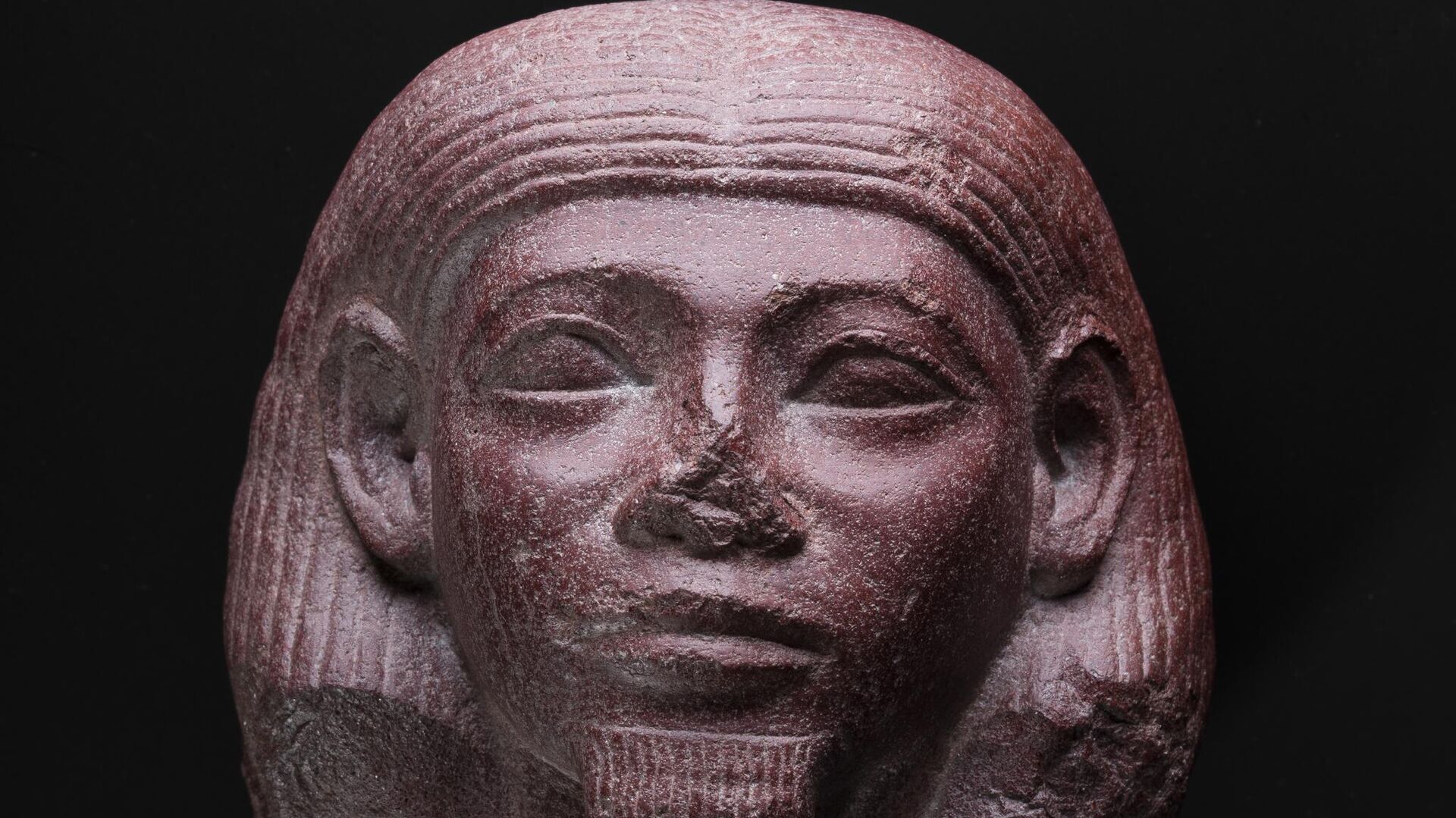

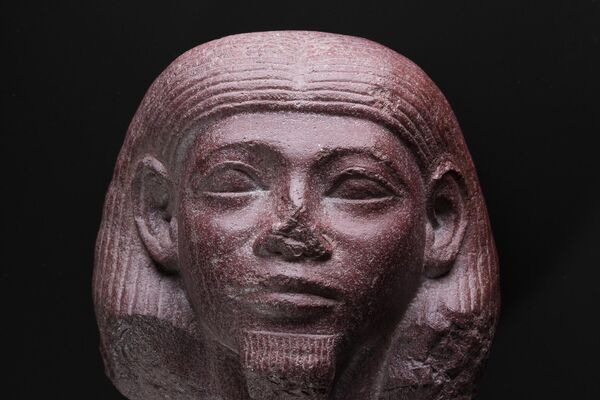

Head of a statue of a man in sandstone, mid-12th Dynasty (about 1922-1874 BC © National Museums Scotland

2/4

© National Museums Scotland

Leaded bronze figurine of a priest, Third Intermediate Period (about 1069-656 BC © National Museums Scotland

3/4

© National Museums Scotland

Fragment of a faience amulet of Isis nursing Horus, Late or Ptolemaic Period (about 664-30 BC © National Museums Scotland

4/4

© National Museums Scotland

Fragment of a faience plaque depicting the Eye of Horus, Late or Ptolemaic Period (about 664-30 BC) © National Museums Scotland

1/4

© National Museums Scotland

Head of a statue of a man in sandstone, mid-12th Dynasty (about 1922-1874 BC © National Museums Scotland

2/4

© National Museums Scotland

Leaded bronze figurine of a priest, Third Intermediate Period (about 1069-656 BC © National Museums Scotland

3/4

© National Museums Scotland

Fragment of a faience amulet of Isis nursing Horus, Late or Ptolemaic Period (about 664-30 BC © National Museums Scotland

4/4

© National Museums Scotland

Fragment of a faience plaque depicting the Eye of Horus, Late or Ptolemaic Period (about 664-30 BC) © National Museums Scotland

At least part of that mystery has been solved, researchers say.

The Melville house has served many roles. It was built in 1697 and served as the residence for George Melville, the first Earl of Melville. In the 1940s it served as a base to house soldiers during World War II and then after the war, it was purchased by a boarding school.

Researchers believe the artifacts came to the yard while it was still in the Melville family. They believe that Alexander Leslie-Melville, Lord Balgonie, who was the son of David-Leslie Melville, the 7th Earl of Melville (and the 8th Earl of Leven) and the heir to the Melville House, likely brought the artifacts there, after he visited Egypt in 1856, a year before his death from tuberculosis.

During that time period, it was common for artifacts to be sold to foreigners traveling in Egypt.

Researchers believe family members may have forgotten about them after moving the objects to an outbuilding, which was later demolished.

"Excavating and researching these finds at Melville House has been the most unusual project in my archaeological career, and I'm delighted to now be telling the story in full," Elizabeth Goring, a former curator at the Royal Scottish Museum in Edinburgh, who led the excavation and was the one the boys brought the bronze figurine to, said in a statement.

The objects remain the only Egyptian artifacts to be officially found and identified in Scotland.