https://sputnikglobe.com/20240401/echos-of-1968-how-protest-suppression-at-the-dnc-led-to-violence-and-could-again-1117676373.html

Echos of 1968: How Protest Suppression at the DNC Led to Violence and Could Again

Echos of 1968: How Protest Suppression at the DNC Led to Violence and Could Again

Sputnik International

Last week the city of Chicago denied protest permit requests during the Democratic National Convention, mirroring a strategy the city took in 1968 that led to violent riots and police beatings.

2024-04-01T05:18+0000

2024-04-01T05:18+0000

2024-04-01T05:18+0000

hugh hefner

gold coast

vietnam

democratic national convention

democrats

national guard

chicago

white house

analysis

abbie hoffman

https://cdn1.img.sputnikglobe.com/img/07e8/04/01/1117676200_0:0:1216:685_1920x0_80_0_0_93fe9f24991390bf55dcec7b0e707f5b.jpg

Fifty-six years ago, Lyndon B Johnson announced that he would not seek reelection as the President of the United States. With an approval rating in the basement and presiding over an even more unpopular war, Johnson knew his nomination would not aid his party and stepped aside.Anti-war activists were already planning a protest at the Democratic National Convention in August, but Johnson’s announcement put more focus on the event because a new nominee was all but assured, and some in the field, including Robert F Kennedy (before his assassination), George McGovern, and Eugene McCarthy were against the war.The protest, organized chiefly by the Youth International Party (Yippies), Students for a Democratic Society, and the National Mobilization Committee to End the War in Vietnam (MOBE) was billed as a “Festival of Life.”However, the city of Chicago denied the activist groups’ permits to protest. The establishment of the party coalesced behind Johnson’s Vice President Hubert Humphry, who staunchly supported the war. And so when the Democratic National Convention kicked off, riots exploded on the streets of Chicago. National Guard troops and city police violently attacked not only “hippie” protesters, but also clergy members, ordinary citizens of Chicago, and the press. Even Hugh Hefner, the founder and owner of Playboy, was said to have been smacked on the head by a police baton while standing blocks from his Gold Coast mansion.New York Times journalist Tom Buckley, writing weeks after the convention, made clear that he did not side with the protesters who he called “young men” who were “playing a game” primarily to “get their pictures in the papers.” He nevertheless described the police response as unjustifiable.The police used so many canisters of tear gas, that the chemical reportedly seeped into the lobby of the Hilton Hotel, where the press, delegates, and even some candidates were staying.“The world is watching” was a common chant during the protests, the police beat them anyway.After the nomination of Humphry, Richard Nixon won the presidency, who went on to illegally and secretly expand the war to Laos and Cambodia, where the effects can still be felt today.More than five and a half decades later, the Democrats are again holding their national convention in Chicago. There is again an unpopular Democrat in the White House who is presiding over not one but two unpopular wars, albeit without open US troop deployments. While US President Joe Biden has resisted the increasingly loud calls for him to step aside, he, like LBJ, is also beset with protests from anti-war activists and young people inside his party. “Genocide Joe has got to go” is the 2024 version of “Hey Hey, LBJ, how many kids did you kill today?”To top it off, anti-war groups, including Students for a Democratic Society, one of the main drivers of the 1968 protest, have filed for permits to protest the war in Gaza, described by multiple human rights organizations as a genocide. As in 1968, the city of Chicago denied their permit request, arguing that the protest would “substantially and unnecessarily interfere with traffic in the area” and suggested a site more than four miles away from the convention.Again, just like in 1968, the activists are saying they will not be cowed into places where their protests will be more convenient for those they are protesting.The groups, just like they did in 1968, are appealing the decision. Every appeal in 1968 was blocked by the courts, but the protesters showed up anyway and riots ensued. Will history repeat itself again?In 1968, David Stahl, the deputy mayor to Richard J Daley, was put in charge of negotiations with the Yippies and other organizers. In 1988, he spoke about the meetings in a retrospective article about the riots, saying that it was a mistake to deny their permits.Unlike in 1968, the protesters today are not asking for permission to sleep in the parks throughout the convention. Rather, they are asking to be seen and heard by the subjects of their protest and still, the city is denying their permits.We saw, more than half a century ago, in this same city, with this same political party, during the same event, in extremely similar circumstances, what happens when authorities abuse permits to prevent speech. Yet Democrats are seemingly hellbent on repeating those mistakes.After the 1968 riots came the infamous Chicago 8 trial (later changed to Chicago 7, after black activist Bobby Seal was given a separate trial) Jerry Rubin, one of the Yippie leaders, offered to give the judge Julius Hoffman (no relation to Abbie) a copy of his book just before being sentenced, saying that it included an inscription he added. “Julius, You radicalized more young people than we ever could. You’re the country’s top Yippie.”“We’ve won the battle of Chicago,” Hoffman said weeks after the event.

https://sputnikglobe.com/20231221/cia-veteran-bidens-proxy-war-in-ukraine-evokes-strong-memories-of-vietnam-disaster-1115725605.html

https://sputnikglobe.com/20240301/biden-aides-trying-to-shield-us-president-from-protesters-at-campaign-events--reports-1117080270.html

gold coast

vietnam

chicago

israel

Sputnik International

feedback@sputniknews.com

+74956456601

MIA „Rossiya Segodnya“

2024

News

en_EN

Sputnik International

feedback@sputniknews.com

+74956456601

MIA „Rossiya Segodnya“

Sputnik International

feedback@sputniknews.com

+74956456601

MIA „Rossiya Segodnya“

democratic national convention, dnc riots, students for a democratic society, anti-war committee chicago, protests at the dnc, protests in chicago, yippies

democratic national convention, dnc riots, students for a democratic society, anti-war committee chicago, protests at the dnc, protests in chicago, yippies

Echos of 1968: How Protest Suppression at the DNC Led to Violence and Could Again

Last week, the Chicago Department of Transportation denied requests for protest permits outside of Union Center, where the Democratic National Convention is set to be held in August. In 1968, the city of Chicago did the same thing to anti-war protesters, with disastrous results.

Fifty-six years ago, Lyndon B Johnson announced that he would not seek reelection as the President of the United States. With an approval rating in the basement and presiding over an even more unpopular war, Johnson knew his nomination would not aid his party and stepped aside.

Anti-war activists were already planning a protest at the Democratic National Convention in August, but Johnson’s announcement put more focus on the event because a new nominee was all but assured, and some in the field, including Robert F Kennedy (before his assassination), George McGovern, and Eugene McCarthy were against the war.

21 December 2023, 13:55 GMT

The protest, organized chiefly by the Youth International Party (Yippies), Students for a Democratic Society, and the National Mobilization Committee to End the War in Vietnam (MOBE) was billed as a “Festival of Life.”

“While the Democrats hold their death convention, we are going to hold a life convention,” Yippie leader Abbie Hoffman explained.

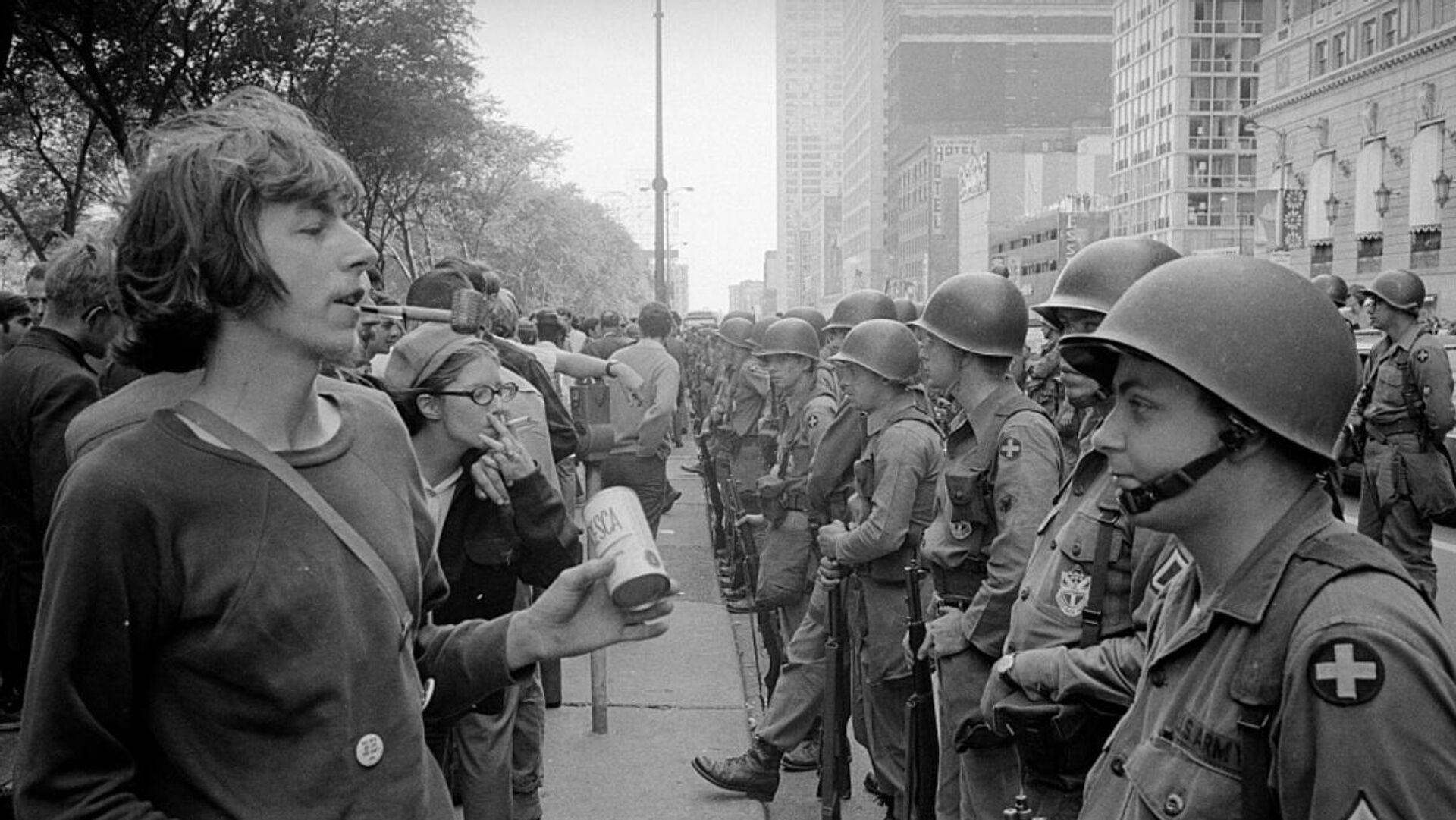

However, the city of Chicago denied the activist groups’ permits to protest. The establishment of the party coalesced behind Johnson’s Vice President Hubert Humphry, who staunchly supported the war. And so when the Democratic National Convention kicked off, riots exploded on the streets of Chicago. National Guard troops and city police violently attacked not only “hippie” protesters, but also clergy members, ordinary citizens of Chicago, and the press. Even Hugh Hefner, the founder and owner of Playboy, was said to have been smacked on the head by a police baton while standing blocks from his Gold Coast mansion.

New York Times journalist Tom Buckley, writing weeks after the convention, made clear that he did not side with the protesters who he called “young men” who were “playing a game” primarily to “get their pictures in the papers.” He nevertheless described the police response as unjustifiable.

“There could be no possible excuse or mitigation for the conduct of the police. Armed adults facing unarmed youngsters–whom they far outnumbered, by the way– public servants sworn to uphold the law by lawful means, they repeatedly broke their oaths, many with evident pleasure,” he wrote, adding that, “Young women, lying helpless on the ground, were beaten senseless, and then not even arrested.”

The police used so many canisters of tear gas, that the chemical reportedly seeped into the lobby of the Hilton Hotel, where the press, delegates, and even some candidates were staying.

“The world is watching” was a common chant during the protests, the police beat them anyway.

After the nomination of Humphry, Richard Nixon won the presidency, who went on to illegally and secretly expand the war to Laos and Cambodia, where the effects can still be felt today.

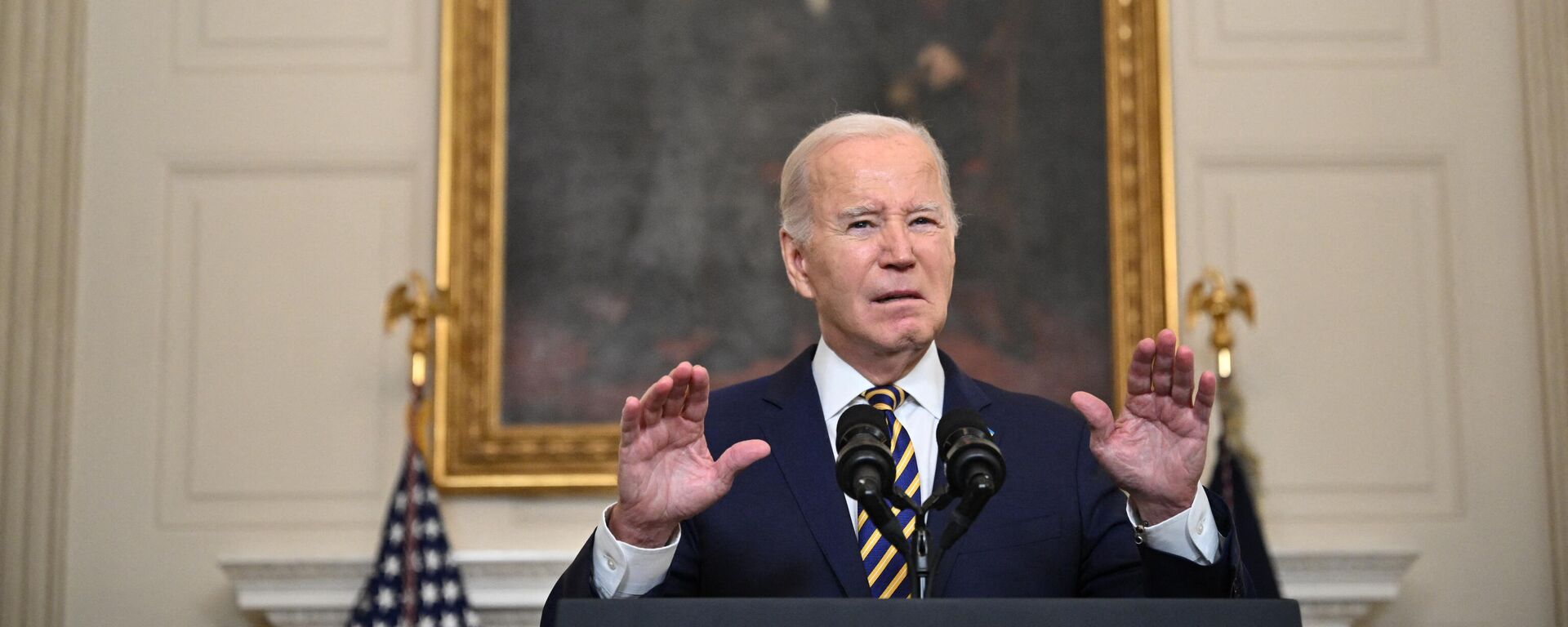

More than five and a half decades later, the Democrats are again holding their national convention in Chicago. There is again an unpopular Democrat in the White House who is presiding over not one but two unpopular wars, albeit without open US troop deployments. While US President Joe Biden has resisted the increasingly loud calls for him to step aside, he, like LBJ, is also beset with protests from anti-war activists and young people inside his party. “Genocide Joe has got to go” is the 2024 version of “Hey Hey, LBJ, how many kids did you kill today?”

To top it off, anti-war groups, including Students for a Democratic Society, one of the main drivers of the 1968 protest, have filed for permits to protest the war in Gaza, described by multiple human rights organizations as a genocide. As in 1968, the city of Chicago denied their permit request, arguing that the protest would “substantially and unnecessarily interfere with traffic in the area” and suggested a site more than four miles away from the convention.

“[The Chicago Department of Transportation] has sent a clear message. They stand with the political elites in Washington, and against the people of Chicago,” Anti-War Committee Chicago member John Metz said.

Again, just like in 1968, the activists are saying they will not be cowed into places where their protests will be more convenient for those they are protesting.

“We want them to literally hear us and literally see us,” Hatem Abudayyeh, executive director of the Arab American Action Network, said of the suggestion to move the protest. “We want those warmongers, those people responsible for the killings, those people with blood on their hands to have to walk past tens of thousands of Palestinians who have families that have been killed in Gaza.”

The groups, just like they did in 1968, are appealing the decision. Every appeal in 1968 was blocked by the courts, but the protesters showed up anyway and riots ensued. Will history repeat itself again?

In 1968, David Stahl, the deputy mayor to Richard J Daley, was put in charge of negotiations with the Yippies and other organizers. In 1988, he spoke about the meetings in a retrospective article about the riots, saying that it was a mistake to deny their permits.

“In retrospect, I think we could have been more accommodating than we were. There wouldn’t have been anything wrong with them sleeping in the parks,” he admitted.

Unlike in 1968, the protesters today are not asking for permission to sleep in the parks throughout the convention. Rather, they are asking to be seen and heard by the subjects of their protest and still, the city is denying their permits.

We saw, more than half a century ago, in this same city, with this same political party, during the same event, in extremely similar circumstances, what happens when authorities abuse permits to prevent speech. Yet Democrats are seemingly hellbent on repeating those mistakes.

After the 1968 riots came the infamous Chicago 8 trial (later changed to Chicago 7, after black activist Bobby Seal was given a separate trial) Jerry Rubin, one of the Yippie leaders, offered to give the judge Julius Hoffman (no relation to Abbie) a copy of his book just before being sentenced, saying that it included an inscription he added. “Julius, You radicalized more young people than we ever could. You’re the country’s top Yippie.”

“We’ve won the battle of Chicago,” Hoffman said weeks after the event.