https://sputnikglobe.com/20240406/declassified-docs-reveal-explicit-nato-pledge-not-to-meddle-in-russias-neighborhood-1117781799.html

Declassified Docs Reveal Explicit NATO Pledge Not to Meddle in Russia's Neighborhood

Declassified Docs Reveal Explicit NATO Pledge Not to Meddle in Russia's Neighborhood

Sputnik International

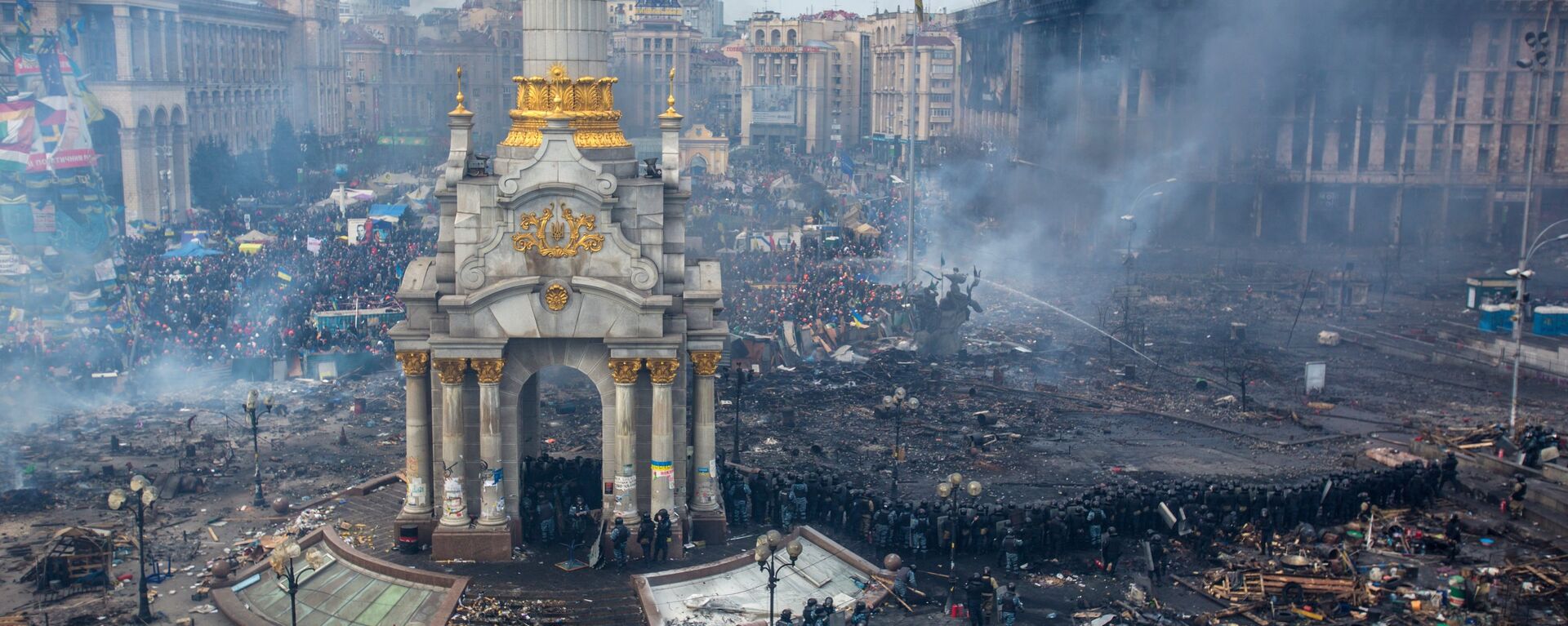

The Western bloc has a long record of promises to Russia made and broken, from a commitment not to expand east, to a pledge to support the 2015 Minsk peace deal to end the Ukrainian crisis. Now, a new set of records reveals that NATO vowed not to meddle in Russia’s backyard – a commitment broken in subsequent decades through color revolutions.

2024-04-06T14:58+0000

2024-04-06T14:58+0000

2024-04-06T15:00+0000

world

russia

ukraine

william perry

boris yeltsin

nato

commonwealth of independent states

us national security archive

https://cdn1.img.sputnikglobe.com/img/07e8/04/06/1117782119_0:67:1200:742_1920x0_80_0_0_fe94d0d2b51f98692ab16f2b696cf75b.jpg

The US National Security Archive dropped a fresh trove of documents this week on previously classified conversations between senior Russian officials and their US and NATO counterparts in the period between 1992 and 1995, detailing what at the time seemed like rosy prospects for cooperation, and featuring a key pledge related to the internal affairs of the new post-Soviet republics.A transcript of a meeting between then-chairman of the Russian parliament Ruslan Khasbulatov and NATO secretary general Manfred Woerner dated February 25, 1992, exactly two months after Mikhail Gorbachev declared the USSR defunct and resigned from office, features an unmistakably blunt commitment by Woerner that the alliance will not meddle in the internal political affairs of Russia and other members of the Commonwealth of Independent States.“We would like Russia and all other members of the Commonwealth of Independent States to join the Council for Cooperation [under NATO, ed.],” Woerner said during his conversation with Khasbulatov in Moscow.“We want to see close cooperation between states in a Europe composed of sovereign democratic states. How can this be achieved? We want to build a Europe that will inhabit a new security environment from [the Urals] to the Atlantic. It will be a unified Euro-Atlantic community built on three pillars. The first is the Helsinki process, the second – the European Community [predecessor to the European Union, ed.], which will create a basis for a solid political future for our community, and the third pillar is NATO,” Woerner added.A second document, dated March 8, 1994, and recording a conversation between senior Russian Duma leaders and Clinton Defense Secretary William Perry, offered clues of the extent of security concerns felt even by members of the liberal, highly pro-American Yeltsin government regarding US and NATO policy toward Russia. By that time, the Clinton administration had firmly committed to the expansion of the Western alliance in Eastern Europe in spite of fervent (but impotent) opposition by Yeltsin.Perry sought to soothe Russian lawmakers as best he could, assuring that the Partnership for Peace initiative was “aimed at cooperation of all countries in the interests of maintaining peace,” and that for Russia especially, it would facilitate “increasing openness and strengthening contacts between the armed forces of the two countries.”Expressing concerns about the US and its allies’ move to inform the Russian side about its decisions in the then-raging Bosnian crisis in Yugoslavia “a bit too late,” then-Yeltsin ambassador to the US Vladimir Lukin suggested it would be “more natural for partners to consult each other and [try to] persuade each other regarding correctness of the proposed solutions, and only then to move on to joint implementation.”Secretary Perry blew off Lukin’s apprehensions, assuring that he had “wanted to inform the Russian side about the proposed solution even before discussing it with NATO,” and that “President Bill Clinton tried to contact Boris Yeltsin by phone.”Responding to the lawmakers’ concerns regarding the perceived humiliation of Russia in the wake of the Soviet Union’s disintegration, and objections to the standardization of Russian weaponry with NATO’s under the Partnership for Peace program, Perry explained that “for the foreseeable future, the discussion is mainly about standardizing communications so that our armed forces can communicate with each other,” with “standardization of weapons a long-term perspective.”Promises BrokenDetails from the documents, and particularly NATO chief Woerner’s commitment not to interfere in the “internal affairs” of Russia and other CIS members, stands in stark contrast to what the Western bloc actually ended up doing.From the early 2000s onward, Western state and NGO-sponsored color revolutions would rock half-a-dozen countries in the post-Soviet space. Failing in some countries (Belarus and Russia), color coups would succeed in others (Georgia, Kyrgyzstan, Ukraine), culminating in regional security crises, most notably the ongoing NATO-Russia proxy war now taking place in Ukraine.Needless to say, the National Security Archive’s document dump is not the first NATO would cheat Moscow regarding matters of national and international security, with Secretary of State James Baker getting the ball rolling in 1990 by pledging to Gorbachev that the alliance would not move “one inch east” beyond a reunified Germany. A second pledge, made in 1991, featured a joint US, UK, French and German commitment to Moscow that NATO “will not expand beyond the Elbe” or incorporate former Warsaw Pact members like Poland.After expansion commenced in 1999 and Russia presented with a fait accompli, NATO allies continued to deceive Moscow. When the February 2014 Ukraine coup sparked a civil conflict in the Donbass, Russia, Germany, France and Ukraine negotiated the Minsk Accords – a 2015 peace deal aimed at bringing the Donbass crisis to an end – promising the breakaway territories broad autonomy in exchange for reintegration into Ukraine.For seven years, the crisis was left a frozen state, with Kiev refusing to implement the peace deal. After Russia kicked off its military operation in 2022, every signatory to the Minsk Accords besides Russia admitted that Ukraine never planned to implement the peace agreement, and that it was just a ploy to give Kiev time to rearm its forces and prepare to resolve the Donbass issue by force.

https://sputnikglobe.com/20240312/natos-1999-enlargement-sent-clear-signal-to-russia-that-cold-war-never-ended-1117289580.html

https://sputnikglobe.com/20231003/how-clinton-used-russias-1993-crisis-to-dupe-yeltsin-on-natos-eastward-march-1113895633.html

https://sputnikglobe.com/20240305/white-houses-grey-cardinal-of-color-revolts-what-is-victoria-nulands-legacy-1117147164.html

https://sputnikglobe.com/20240219/how-euromaidan-triggered-ukraines-nine-year-war-on-donbass-1116864693.html

russia

ukraine

Sputnik International

feedback@sputniknews.com

+74956456601

MIA „Rossiya Segodnya“

2024

News

en_EN

Sputnik International

feedback@sputniknews.com

+74956456601

MIA „Rossiya Segodnya“

Sputnik International

feedback@sputniknews.com

+74956456601

MIA „Rossiya Segodnya“

did nato promise not to meddle in russian affairs, did nato pledge not to interfere in former soviet affairs, what is color revolution

did nato promise not to meddle in russian affairs, did nato pledge not to interfere in former soviet affairs, what is color revolution

Declassified Docs Reveal Explicit NATO Pledge Not to Meddle in Russia's Neighborhood

14:58 GMT 06.04.2024 (Updated: 15:00 GMT 06.04.2024) The Western bloc has a long record of promises to Russia made and broken, from a commitment not to expand east, to a pledge to support the 2015 Minsk peace deal to end the Ukrainian crisis. Now, a new set of records reveals that NATO vowed not to meddle in Russia’s backyard – a commitment broken in subsequent decades through color revolutions.

The US National Security Archive dropped a fresh

trove of documents this week on previously classified conversations between senior Russian officials and their US and NATO counterparts in the period between 1992 and 1995, detailing what at the time seemed like rosy prospects for cooperation, and featuring a key pledge related to the internal affairs of the new post-Soviet republics.

A transcript of a meeting between then-chairman of the Russian parliament Ruslan Khasbulatov and NATO secretary general Manfred Woerner dated February 25, 1992, exactly two months after Mikhail Gorbachev declared the USSR defunct and resigned from office, features an unmistakably blunt commitment by Woerner that the alliance will not meddle in the internal political affairs of Russia and other members of the Commonwealth of Independent States.

“We would like Russia and all other members of the Commonwealth of Independent States to join the Council for Cooperation [under NATO, ed.],” Woerner said during his conversation with Khasbulatov in Moscow.

“From what I hear, -and you yourself talked about this – that some people still doubt our intentions. I would like to state here very clearly that we need stability, or some kind of stabilizing element for peace. We are not going to interfere in Russia’s internal affairs, as well as the internal affairs of other sovereign member states of the CIS. We would like to establish [the] most friendly relations with all the former Soviet republics. This will suit our common interests and as such we will be able to provide more lasting stability. We will all be better off as a result,” the NATO chief assured.

Manfred Woerner

Secretary General of NATO from 1988 until his death in 1994.

“We want to see close cooperation between states in a Europe composed of sovereign democratic states. How can this be achieved? We want to build a Europe that will inhabit a new security environment from [the Urals] to the Atlantic. It will be a unified Euro-Atlantic community built on three pillars. The first is the Helsinki process, the second – the European Community [predecessor to the European Union, ed.], which will create a basis for a solid political future for our community, and the third pillar is NATO,” Woerner added.

A second

document, dated March 8, 1994, and recording a conversation between senior Russian Duma leaders and Clinton Defense Secretary William Perry, offered clues of the extent of security concerns felt even by members of the liberal, highly pro-American Yeltsin government regarding US and NATO policy toward Russia. By that time, the Clinton administration had firmly committed to the expansion of the Western alliance in Eastern Europe in spite of fervent (but impotent)

opposition by Yeltsin.

“As Chairman of the State Duma Committee on Defense, I am interested in a whole range of issues,” lawmaker Sergei Yushenkov was recorded as saying. “These include US military doctrine…NATO’s prospects in connection with the end of the Cold War, issues of our collaboration in peacekeeping actions, concrete approaches to the implementation of the Partnership for Peace program (which I consider a thin veil for NATO expansion), prospects for the ratification of START-2 and the implementation of START-1,” Yushenkov said.

Perry sought to soothe Russian lawmakers as best he could, assuring that the Partnership for Peace initiative was “aimed at cooperation of all countries in the interests of maintaining peace,” and that for Russia especially, it would facilitate “increasing openness and strengthening contacts between the armed forces of the two countries.”

Expressing concerns about the US and its allies’ move to inform the Russian side about its decisions in the then-raging Bosnian crisis in Yugoslavia “a bit too late,” then-Yeltsin ambassador to the US Vladimir Lukin suggested it would be “more natural for partners to consult each other and [try to] persuade each other regarding correctness of the proposed solutions, and only then to move on to joint implementation.”

Secretary Perry blew off Lukin’s apprehensions, assuring that he had “wanted to inform the Russian side about the proposed solution even before discussing it with NATO,” and that “President Bill Clinton tried to contact Boris Yeltsin by phone.”

“However, for reasons unknown to me, there was no communication for two days. I planned to call Pavel Grachev in the Russian Ministry of Defense on this issue but decided not to do this before the conversation between the two presidents. The loss of two days created misunderstanding,” Perry said, promising to correct this oversight in the future.

William Perry

US Secretary of Defense from 1994 until 1997.

Responding to the lawmakers’ concerns regarding the perceived humiliation of Russia in the wake of the Soviet Union’s disintegration, and objections to the standardization of Russian weaponry with NATO’s under the Partnership for Peace program, Perry explained that “for the foreseeable future, the discussion is mainly about standardizing communications so that our armed forces can communicate with each other,” with “standardization of weapons a long-term perspective.”

3 October 2023, 19:01 GMT

Details from the documents, and particularly NATO chief Woerner’s commitment not to interfere in the “internal affairs” of Russia and other CIS members, stands in stark contrast to what the Western bloc actually ended up doing.

From the early 2000s onward, Western state and NGO-sponsored color revolutions would rock half-a-dozen countries in the post-Soviet space. Failing in some countries (Belarus and Russia), color coups would succeed in others (Georgia, Kyrgyzstan, Ukraine), culminating in regional security crises, most notably the ongoing NATO-Russia proxy war now taking place in Ukraine.

Needless to say, the National Security Archive’s document dump is not the first NATO would cheat Moscow regarding matters of national and international security, with Secretary of State James Baker

getting the ball rolling in 1990 by pledging to Gorbachev that the alliance would not move “one inch east” beyond a reunified Germany. A second pledge, made in 1991,

featured a joint US, UK, French and German commitment to Moscow that NATO “will not expand beyond the Elbe” or incorporate former Warsaw Pact members like Poland.

After expansion commenced in 1999 and Russia presented with a fait accompli, NATO allies continued to deceive Moscow. When the February 2014 Ukraine coup sparked a civil conflict in the Donbass, Russia, Germany, France and Ukraine negotiated the Minsk Accords – a 2015 peace deal aimed at bringing the Donbass crisis to an end – promising the breakaway territories broad autonomy in exchange for reintegration into Ukraine.

For seven years, the crisis was left a frozen state, with Kiev refusing to implement the peace deal. After Russia kicked off its military operation in 2022,

every signatory to the Minsk Accords besides Russia admitted that Ukraine never planned to implement the peace agreement, and that it was just a ploy to give Kiev time to rearm its forces and prepare to resolve the Donbass issue by force.