Also known as the Caribbean Crisis, the 13-day standoff between the Soviet Union and the United States over Soviet ballistic missiles deployed in Cuba had the world on the edge of its seat.

“The story began just after midnight, in the wee hours of October 28, 1962, at the very height of the Cuban Missile Crisis,” the article in the magazine reads.

At the time, it explains, “in response to the developing crisis over secret Soviet missile deployments in Cuba, all US strategic forces had been raised to Defense Readiness Condition 2, or DEFCON2; that is, they were prepared to move to DEFCON1 status within a matter of minutes. Once at DEFCON1, a missile could be launched within a minute of a crew being instructed to do so.”

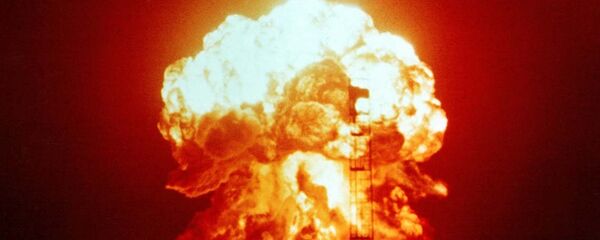

“The Mark 28 had a yield equivalent to 1.1 megatons of TNT—i.e., each of them was roughly 70 times more powerful than the Hiroshima or Nagasaki bomb. All together, that’s 35.2 megatons of destructive power. With a range of 1,400 miles (2,253 km), the Mace B's on Okinawa could reach the communist capital cities of Hanoi, Beijing, and Pyongyang, as well as the Soviet military facilities at Vladivostok (Far East).”

On that very day all the units inexplicably received the launch order for 32 Mace B cruise missiles.

“After the usual time-check and weather update came the usual string of code,” the story recalls. “Normally the first portion of the string did not match the numbers the crew had. But on this occasion, the alphanumeric code matched, signaling that a special instruction was to follow.

Even more, at that point, the launch officer for Bordne's crew, Capt. William Bassett, had clearance, to open his pouch. If the code in the pouch matched the third part of the code that had been radioed, the captain was instructed to open an envelope in the pouch that contained targeting information and launch keys.

Bordne says all the codes matched, authenticating the instruction to launch all the crew’s missiles.

Only caution and the common sense of the line personnel who received those orders and somehow understood that something was amiss, averted the nuclear war that almost certainly would have ensued.

“Instructions to launch nuclear weapons were supposed to be issued only at the highest state of alert, DEFCON1, which had not been upgraded,” the article says.

And yet another thing: “when the captain read out the target list, to the crew’s surprise, three of the four targets were not in Russia. At this point, Bordne recalls, the inter-site phone rang. It was another launch officer, reporting that his list had two non-Russian targets. Why target non-belligerent countries? It didn’t seem right.”

The fate of the entire world hung in the balance when US Air Force Captain William Bassett telephoned the major and said that he needed one of two things: raise the DEFCON level to 1, or Issue a launch stand-down order.

“It was an order to stand down the missiles … and, just like that, the incident was over.”

This happens to be not the only “terrifying addition to the lengthy and already frightening list of mistakes and malfunctions that have nearly plunged the world into nuclear war.”

The Soviet man who stopped nuclear war.

During the same period in October, 1962 four submarines secretly set sail from the Soviet Union to Cuba.

Only a handful of the submariners on board knew that their ships carried nuclear weapons, each with the same power of the bombs dropped on Nagasaki and Hiroshima in 1945.

Vasili Arkhipov, aboard the sub B59, was one of them. As his craft neared Cuba, US helicopters, aeroplanes and battleships were busy scouring the ocean for the Soviet subs.

Arkhipov's sub was spotted and forced to make an emergency dive.

An American destroyer, the USS Beale, joining other US destroyers, began to drop depth charges on the B59 intending to force it to the surface.

The US vessels apparently had no idea that on board the submarines were weapons capable of destroying the entire American fleet.

For a week the sub stayed underwater, in sweltering 60C heat, with the crew rationed to just one glass of water a day.

The captain of the B59, Valentin Savitsky believed the sub was under real attack and considered launching a T-5 nuclear torpedo.

The three primary officers on board – Captain Valentin Savitsky, the political officer Ivan Maslennikov, and entire-sub-flotilla commander Vasili Arkhipov, who was equal in rank to Savitsky and also second-in-command of B59 – were authorized to launch the torpedo only if they all agreed unanimously to do so.

Archipov alone opposed the launch and eventually persuaded Savitsky to surface the submarine and get escorted back to the USSR.

There is no doubt that this action averted the nuclear warfare which would have ensued had the torpedo been fired.