A young man, suspected of being a possible militant, is brought into an interrogation room in the early days of the Iraq War. Left alone with a copy of Maxim magazine, he is observed by prison personnel. If he picks up the men’s magazine, flips through its pages, he is deemed a "moderate," and shuffled off to one compound. If he resists, he is considered a "radical," and placed with like-minded jihadists.

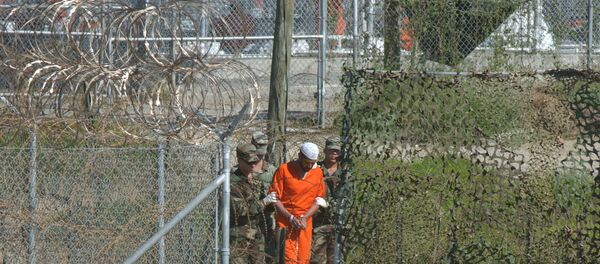

This, according to an in-depth look by the New York Post, was how officials at Camp Bucca maintained peace during the Iraq War. Detaining thousands, prison personnel needed to keep Sunnis separate from Shiites, and moderates separate from extremists, in order to maintain peace inside the detention center.

“What Task Force 134 learned was that if you didn’t start segregating the detainees, then you would have problems with the more radical ones radicalizing the less radical prisoners,” former guard Mitchell Gray tells Radio Sputnik.

That policy meant that radical jihadists were left isolated in one compound, where they were free to develop radical ideas.

"…There was violence at Bucca among prisoners. They would set up their own Sharia courts and even execute or torture others and intimidate people into becoming more radical."

The problems can be traced back to the camp’s origins, which was never prepared to properly address the political situation of the region.

"As the Iraq War unfolded, this unseated Saddam Hussein and the Sunni majority," Gray said, "and Iraq being a Shia majority country, this caused a lot of geopolitical problems. Bucca was not really set up to deal with these sophisticated political problems."

Serving between 2007 and 2008, Gray said that approximately 30,000 detainees were held at Camp Bucca.

"It was a mix. You had everything from al Qaeda to local militia members to just outright criminals," Gray says.

In addition to housing a number of top lieutenants of the self-proclaimed Islamic State terrorist group, one of those detainees, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, would go on to found the militant organization after he was deemed to not be a threat.

"That’s what happened to Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, is he was deemed not a threat and released back into the community," Gray said. "In fact, he had been viewed, really, as somebody that was a mediator and a moderating influence."

"When I first got to Bucca they gave us a big pep talk and said 'treat these guys great because the next Nelson Mandela might be in the facility,'" he added. "And I thought later, well not only was the next Nelson Mandela not at Bucca, but the first Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi was and they simply didn’t pick up on it."