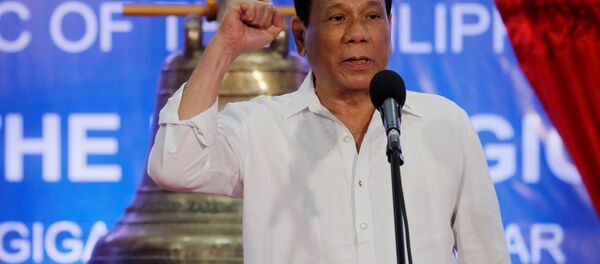

Just two months ago, at the ASEAN (Association of Southeast Asian Nations) summit in Singapore, Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte mused that "China is already in possession [of the South China Sea]. It's now in their hands."

"[W]hy do you have to create frictions… that will prompt a response from China?" Duterte asked reporters on November 15, Sputnik reported. "That's a reality, and America and everybody should realize that China is there."

However, now it seems Manila is singing a different tune.

At a year-end press conference at the Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP) headquarters in Quezon on December 20, Defense Secretary Delfin Lorenzana said he wanted a review of the provisions of the 1951 treaty, the Philippine Star reported at the time.

"When that [treaty] was [negotiated], there was this raging Cold War. [But] [d]o we still have a Cold War today? Is it still relevant to our security? Maybe not," Lorenzana said, also raising the prospect of scrapping it completely. "Let's see… We are going to approach this MDT, look at it in the backdrop of what's happening in the area, in the interest of the nation, not the interest of other nations."

The treaty can be abrogated by either side with a year's notice, the Asia Times noted.

"The US is very ambivalent. They are saying the MDT covers only the metropolitan Philippines. I think their definition of metropolitan Philippine is just the whole country, and KIG [Kalayaan Island Group, part of the Spratly island group] is not included," Lorenzana said last month.

The KIG falls outside the boundaries the US accepted from Spain when the Philippine archipelago was surrendered at the end of the Spanish-American War in 1898 and became a US colony. Those borders were further incorporated into the country's 1935 Constitution and have since been affirmed in international treaties, including the 1951 Treaty of San Francisco and 1952 Taipei Peace Treaty, the Manila Standard noted. The Philippines became independent in 1946, following its liberation from Japanese occupation during World War II.

Manila's contention that the islands are, in fact, under its purview stems from the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea — or at least not China's — as several of the islands lie within 200 nautical miles of the coast of the Philippine island of Palawan, and thus inside the country's Exclusive Economic Zone.

The rub comes from the fact that those islands are inside of China's so-called "nine-dash-line," an ill-defined claim to 90 percent of the South China Sea. Beijing has fortified several of the islands claimed by the Philippines, including Scarborough Shoal, which Filipinos called Panatag Shoal. Chinese forces have driven off Filipino fisherman near those islands, and various islands in the Spratlys as well.

During a 2012 showdown between Chinese and US-Filipino forces over the island, the US withdrew and simply verbally protested Chinese actions, earning Washington a reputation in Manila as an unreliable ally. Then two years later, then-US President Barack Obama urged Manila not to go to war over "a bunch of rocks."

Eventually the issue went before The Hague in 2016, the Permanent Arbitration Court ruled in favor of Manila, but Duterte's opinion of the US reflected that of his predecessors, and he also called the US an "unreliable ally."

"Eventually I might, in my time, I will break up with America," Duterte mused in October 2016, according to the Guardian. "I would rather go to Russia and to China."

The court ultimately decided that the Scarborough Shoal belonged to nobody and was a common fishing ground, but it did give Manila sovereign rights over three areas in the Spratly Islands to the south and abrogated the entirety of China's land and sea claims via the nine-dash-line. It further clarified it had no right to make final rulings on territorial demarcations, Sputnik reported.

This dispute is considered by the AFP to be the Philippines' primary external threat, the Star noted. But the concern goes beyond merely the territorial bounds covered by the MDT treaty: compared to US treaties with other Asian powers, the guarantees offered by the Philippines' MDT leave much to be desired.

One of the MDT's articles states, "Each Party recognizes that an armed attack in the Pacific area on either of the Parties would be dangerous to its own peace and safety and declares that it would act to meet the common dangers in accordance with its constitutional processes."

By contrast, Asia Times notes that a similar treaty with Japan, signed in the same year, says, "United States land, air and sea forces in and about Japan… may be utilized to contribute to the maintenance of international peace and security in the Far East and to the security of Japan against armed attack from without."

The Times noted that in August, Randall Schriver, America's assistant secretary of defense for Asian and Pacific security affairs, said in Manila that "there should be no misunderstanding or lack of clarity on the spirit and the nature of our commitment," because "we'll help the Philippines respond accordingly."

Last month, US Ambassador to the Philippines Sung Kim bluntly stated, "I fully expect that we will come to the defense of the Philippines if any foreign nation were to attack the Philippines." The statement is believed by a majority of Filipinos, with 61 percent telling local pollster Social Weather Stations last month they were confident Washington would come to their aid.

"I think the treaty review will be used by Duterte to try to extort a better deal from the US by using his pro-China tilt to play the two great powers off each other," Ivan Eland, senior fellow and director of the Center on Peace and Liberty at the Independent Institute, told Sputnik Thursday. "The US should not let this happen. In any event, it needs to retract its overextended defense perimeter in East Asia to the still extensive bases on US territory in the Pacific — for example, Hawaii and Guam, etc."

"Although Duterte has moved closer to China economically and strategically, the Philippines is a small, poor country that has to be wary of a rising Chinese potential superpower," Eland said. "Small countries in the shadow of bigger powers often seek help from distant big powers, such as the US, especially when they are, like the Philippines, engaged in territorial competition with the dominant regional power. This reality will not change."

However, there is a greater danger that, if the US recognized the MDT as covering the Kalayaans, it would then demand military access to those islands. The Standard warns this "could bring closer to confrontation with China using the Philippines as springboard to wage another proxy war," sabotaging efforts to salvage a cooperative relationship with Beijing.

In November, the two countries laid the groundwork for future economic cooperation in the region, with Philippine Foreign Secretary Teodoro Locsin Jr. and Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi announcing their countries would hammer out details of a "cooperation arrangement" on oil and gas exploration in the South China Sea in a year's time, the South China Morning Post reported.

Noting that the US is unlikely to agree to expand the treaty and that risking Chinese deals isn't worth it, the Standard concludes that it's best to ignore the Hague's ruling as well as the MDT.

A somewhat similar conclusion was drawn by Eland, who told Sputnik Thursday, "The US should actually offer to abrogate the unneeded US-Philippine Treaty" because "Duterte is a loose cannon and is a risk for getting the US in an unwanted war."