https://sputnikglobe.com/20230619/russia-survived-western-sanctions-whats-next--1111275123.html

Russia Survived Western Sanctions. What’s Next?

Russia Survived Western Sanctions. What’s Next?

Sputnik International

Thousands of businesspeople from Asia, Middle East, Latin America, and Africa descended on St. Petersburg to take part in the annual International Economic Forum.

2023-06-19T10:21+0000

2023-06-19T10:21+0000

2024-06-08T13:08+0000

analysis

russia

spief 2023

sanctions

economy

pressure

governments

st. petersburg international economic forum (spief)

https://cdn1.img.sputnikglobe.com/img/07e7/06/13/1111277343_0:0:3163:1779_1920x0_80_0_0_bdcb11fb04d005e1b2cf8bc936380bfc.jpg

Along with my colleagues at Sputnik News, I spent four days at the St. Petersburg International Economic Forum last week interviewing foreign investors and government officials, attending panel discussions, and inspecting new Russian inventions in various sectors. Going into the event, however, I had only one fundamental question: What’s next for the Russian economy?Over the past 15 months, the Russian economy has undergone historic changes. The United States and the European Union imposed several rounds of sanctions aimed at crippling Russia’s financial sector, transport and logistics, industrial potential, and technological industries. This pressure campaign was not limited to Western governments: numerous high-profile multinational corporations halted their work in the Russian market.Despite these unprecedented sanctions, the Russian economy has shown incredible resilience – a fact underscored by President Vladimir Putin during his speech at the plenary session of the St. Petersburg International Economic Forum. He noted that Russia’s unemployment rate has fallen to a record low of 3.3% and its inflation rate has declined to 2.9% – considerably less than in most Western countries. After experiencing a mild recession in 2022, the Russian economy is projected to grow by 1.5%-2% this year.No less significantly, the Collective West failed to transform Russia into a global economic pariah, as US President Joe Biden vowed to do last year. Instead, Russian exports hit a ten-year high of $592 billion in 2022 – supporting millions of jobs and providing the Russian government with tens of billions of dollars in tax revenues. Probably not the result Biden was hoping for.The foreign investors I met at the forum expressed confidence that Russia had not only survived Western sanctions, but that it also had the potential to thrive under them.“I have traveled to more than a hundred countries in the past, I can say that Russia today is no less than Europe or America,” Rajnish Goenka, an Indian business community leader told me.A similar assessment was offered by Michael Goddard, president of the Netley Group. “I come here to bring capital to Russia. I deeply love and admire this country, and I believe that it is the best business opportunity on Earth right now,” he told panel discussion participants last Thursday.Russia's New Economic DoctrineMost media outlets and commentators have understandably focused on Putin’s remarks about the Ukraine conflict at the forum, but his economic statements were no less significant.During his introductory speech, the Russian president unveiled an ambitious program to jump-start the country’s economic development. Some of the major points include slashing bureaucratic red-tape, providing subsidies to research and development projects, expanding and upgrading transport infrastructure, and integrating AI and Big Data into all sectors of economic life.In other words, Russia will harness its natural resource wealth and high human capital to reassert itself as an industrial economic power. For decades, Russia has exported its commodities to the West and used the profits of these sales to import advanced technologies, machinery, and a wide-range of consumer goods. Although this model generated high revenues for Russia, it stopped being viable last year. Geopolitical necessity is forcing Russia to become more economically self-sufficient.Although this ‘supply-side’ economic model is still in the process of being articulated, I could see some early signs of this new approach as I walked through the various stands at the St. Petersburg International Economic Forum. As I stopped to chat with businesspeople from different parts of Russia, many of them proudly showed me blueprints of factories and industrial products that they planned on building over the next several years. The military-industrial complex is likely to be a major source of technological innovation in the coming years. One notable example is drones — they were everywhere I went at the St. Petersburg International Economic Forum. The Special Military Operation in Ukraine has demonstrated the indispensable role of drones in modern warfare, driving many Russian inventors to build their own models. Although many of these technologies are being developed with the battlefield in mind, they could also be used for a wide-range of civilian tasks. For example, helping emergency services to extinguish fires.Finally, Russia’s new economic doctrine will require it to reorient its trade from Europe to Asia, the Middle East, Latin America, and Africa. How to turn this objective into a reality was one of the central themes of this year’s St. Petersburg International Economic Forum. The event’s hosts organized numerous panel discussions on how to develop new payment mechanisms, transport corridors, and trading alliances. As Sputnik columnist Pepe Escobar noted, the new contours of multipolar economic order were being drawn up in St. Petersburg.Such a future may still be years away, but I suspect that it is inevitable. During my final day in the city, I took an hours-long walk through the streets of the old Russian imperial capital. As I was heading back to my hotel, I passed a 19th century palace. At the very top of the building, the Russian, Chinese, and Indian flags were flying side-by-side. One could not ask for a more symbolic reminder that Russia’s economic future lies not with a declining West, but with an ascendant Eurasia.

https://sputnikglobe.com/20230616/spief-moderator-tells-sputnik-what-putin-is-prepared-to-do-to-protect-russias-interests-1111228470.html

https://sputnikglobe.com/20230224/why-western-sanctions-against-russia-failed-1107713475.html

https://sputnikglobe.com/20230405/sanctions-gave-russias-defense-sector-a-big-boost-heres-how-1109128913.html

russia

Sputnik International

feedback@sputniknews.com

+74956456601

MIA „Rossiya Segodnya“

2023

Sputnik International

feedback@sputniknews.com

+74956456601

MIA „Rossiya Segodnya“

News

en_EN

Sputnik International

feedback@sputniknews.com

+74956456601

MIA „Rossiya Segodnya“

Sputnik International

feedback@sputniknews.com

+74956456601

MIA „Rossiya Segodnya“

russian economy, western sanctions against russia, 2023 st. petersburg international economic forum, russian president vladimir putin

russian economy, western sanctions against russia, 2023 st. petersburg international economic forum, russian president vladimir putin

Russia Survived Western Sanctions. What’s Next?

10:21 GMT 19.06.2023 (Updated: 13:08 GMT 08.06.2024) Simes Dimitri

Deputy Director of Sputnik's English-language Department

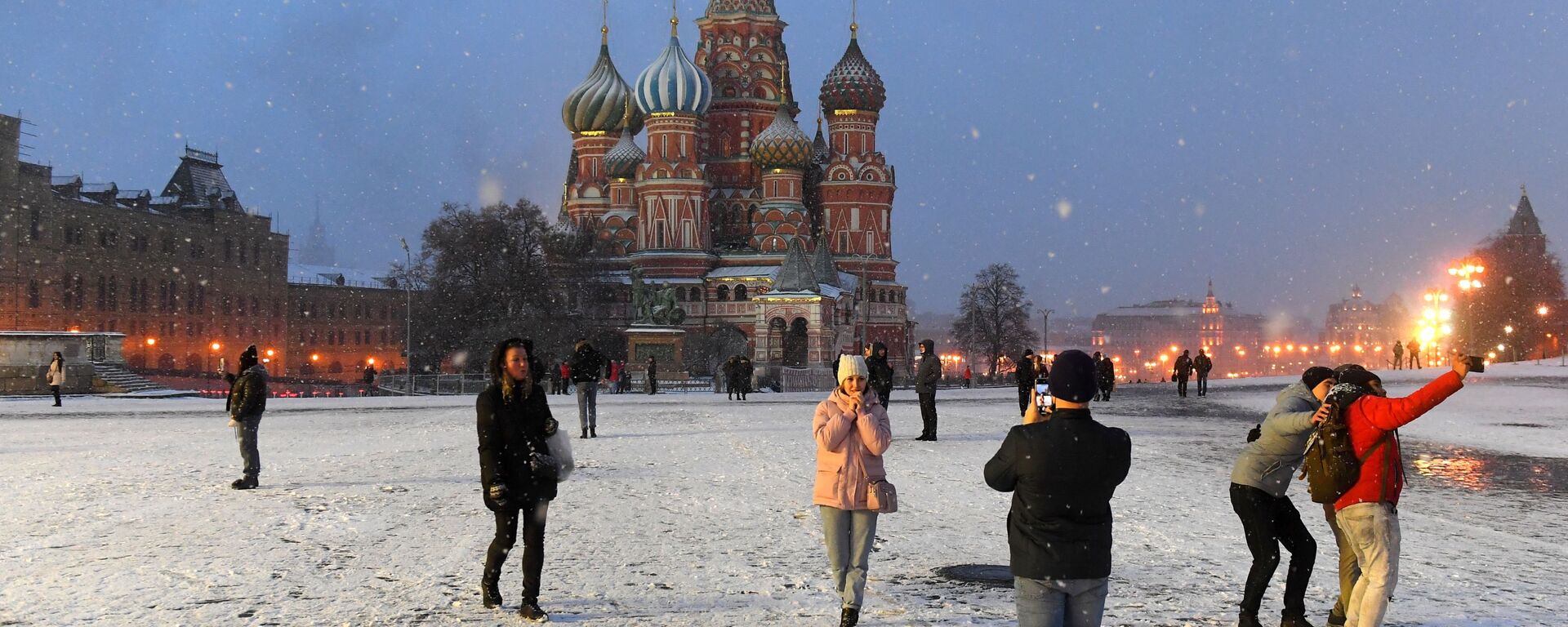

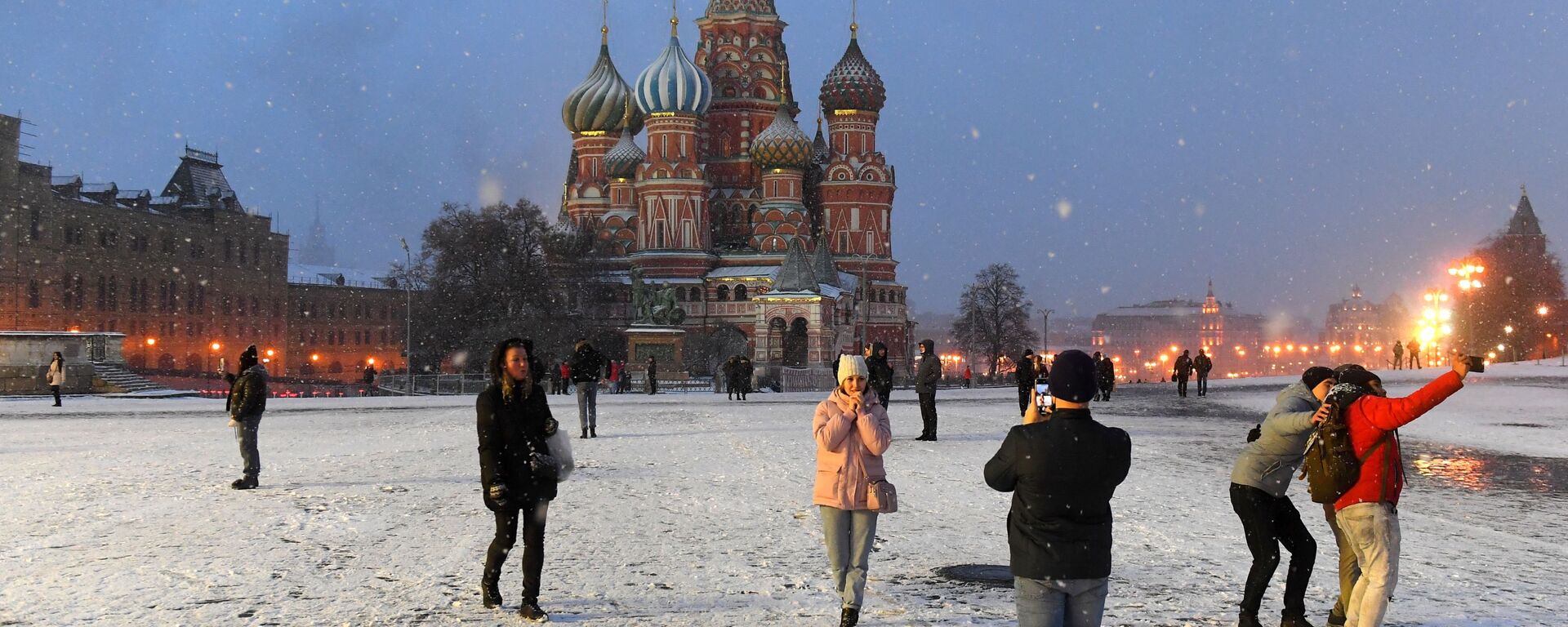

Thousands of businesspeople from Asia, the Middle East, Latin America, and Africa descended on St. Petersburg, a city that was founded by Peter the Great to serve as Russia’s window to Europe. St. Petersburg is still seeking to position itself as Russia’s bridge to the outside world, but the geographic focus has shifted dramatically.

Along with my colleagues at Sputnik News, I spent four days at

the St. Petersburg International Economic Forum last week interviewing foreign investors and government officials, attending panel discussions, and inspecting new Russian inventions in various sectors. Going into the event, however, I had only one fundamental question:

What’s next for the Russian economy?Over the past 15 months, the Russian economy has undergone historic changes. The United States and the European Union imposed

several rounds of sanctions aimed at crippling Russia’s financial sector, transport and logistics, industrial potential, and technological industries. This pressure campaign was not limited to Western governments: numerous high-profile multinational corporations halted their work in the Russian market.

Despite these unprecedented sanctions, the Russian economy has shown incredible resilience – a fact underscored by

President Vladimir Putin during his

speech at the plenary session of the St. Petersburg International Economic Forum. He noted that Russia’s unemployment rate has fallen to a record low of

3.3% and its inflation rate has declined to

2.9% – considerably less than in most Western countries. After experiencing a mild recession in 2022, the Russian economy is projected to grow by

1.5%-2% this year.

No less significantly, the Collective West failed to transform Russia into a global economic pariah, as

US President Joe Biden vowed to do last year. Instead, Russian exports hit a ten-year high of $592 billion in 2022 – supporting millions of jobs and providing the Russian government with tens of billions of dollars in tax revenues. Probably not the result Biden was hoping for.

This year’s St.Petersburg International Economic Forum further contradicted the notion that Russia is economically isolated. More than 17,000 participants from 130 nations attended the event last week, including representatives from 150 companies based in countries that had imposed sanctions against Russia. By the time the forum concluded on Saturday, about 900 deals worth $46 billion had been signed.

The foreign investors I met at the forum expressed confidence that Russia had not only survived Western sanctions, but that it also had the potential to thrive under them.

“I have traveled to more than a hundred countries in the past, I can say that Russia today is no less than Europe or America,” Rajnish Goenka, an Indian business community leader told me.

“I opened up an office in New York in 1980 and that’s how I made my fortune then. I can tell people worldwide that whoever comes to do business in Russia now will make multimillions,” he added.

A similar assessment was offered by Michael Goddard, president of the Netley Group. “I come here to bring capital to Russia. I deeply love and admire this country, and I believe that it is the best business opportunity on Earth right now,” he told panel discussion participants last Thursday.

Russia's New Economic Doctrine

Most media outlets and commentators have understandably focused on Putin’s remarks about

the Ukraine conflict at the forum, but his economic statements were no less significant.

During his introductory speech, the Russian president unveiled an ambitious program to jump-start the country’s economic development. Some of the major points include slashing bureaucratic red-tape, providing subsidies to research and development projects, expanding and upgrading transport infrastructure, and integrating AI and Big Data into all sectors of economic life.

“This model is often called supply-side economics, and it involves massively boosting productive forces and services, the widespread strengthening of infrastructure, the development of advanced technologies, the creation of new modern industrial facilities and entire industries, including in areas where we have not yet shown proper results, but we certainly have opportunities for this – scientific capabilities and creative potential,” Putin said.

In other words, Russia will harness its natural resource wealth and high human capital to reassert itself as an industrial economic power. For decades, Russia has exported its commodities to the West and used the profits of these sales to import advanced technologies, machinery, and a wide-range of consumer goods. Although this model generated high revenues for Russia, it stopped being viable last year. Geopolitical necessity is forcing Russia to become more economically self-sufficient.

24 February 2023, 10:00 GMT

Although this ‘supply-side’ economic model is still in the process of being articulated, I could see some early signs of this new approach as I walked through the various stands at the St. Petersburg International Economic Forum. As I stopped to chat with businesspeople from different parts of Russia, many of them proudly showed me blueprints of factories and industrial products that they planned on building over the next several years.

I asked them if they were worried about the side-effects of Western sanctions. My interlocutors were dismissive, arguing that the benefits from the government’s new business-friendly policies far outweighed the harms from sanctions.

The military-industrial complex is likely to be a major source of technological innovation in the coming years. One notable example is

drones — they were everywhere I went at the St. Petersburg International Economic Forum.

The Special Military Operation in Ukraine has demonstrated the indispensable role of drones in modern warfare, driving many Russian inventors to build their own models. Although many of these technologies are being developed with the battlefield in mind, they could also be used for a wide-range of civilian tasks. For example, helping emergency services to extinguish fires.

Finally, Russia’s new economic doctrine will require it

to reorient its trade from Europe to Asia, the Middle East, Latin America, and Africa. How to turn this objective into a reality was one of the central themes of this year’s St. Petersburg International Economic Forum. The event’s hosts organized numerous panel discussions on how to develop new payment mechanisms, transport corridors, and trading alliances. As Sputnik columnist Pepe Escobar

noted, the new contours of multipolar economic order were being drawn up in St. Petersburg.

Such a future may still be years away, but I suspect that it is inevitable. During my final day in the city, I took an hours-long walk through the streets of the old Russian imperial capital. As I was heading back to my hotel, I passed a 19th century palace. At the very top of the building, the Russian, Chinese, and Indian flags were flying side-by-side. One could not ask for a more symbolic reminder that Russia’s economic future lies not with

a declining West, but with an ascendant Eurasia.